Oil crises in 1973 and 1979 drove Iceland to reconsider its energy infrastructure, shifting from heavy oil and coal use to domestic sources of energy [1]. This island country’s geographical location and geological activity has yielded a diverse landscape rich in geothermal and hydrological resources. Shaped by powerfully gradual additive and subtractive processes from lava, ice, and water, Icelanders treasure their residency in this dynamic territory that consistently inspires awe. Famously known for its Sagas and folklore, these Icelandic stories highlight critical relationships between culture and landscape, forming sacred places across the country. With an abundance of heated subsurface water and rapidly moving surface water, the Icelandic government saw opportunity to create an energy independent country by tapping into these renewable resources. Extractive methods from the oil and gas industries were adopted to harvest geothermal energy—drilling wells, and pumping and conveying water to generate electricity, while methods from dam making to generate hydropower were adopted at monumental scales. Although these forms of energy production are renewable when compared to oil and gas, they also create both foreseen and unforeseen spatial and material byproducts of abruptly altered landscapes. Icelandic pride in the scenic beauty of their landscape and in the development of domestic forms of renewable energy production are both strongly cultural, and is a tension that has amplified over the last two decades as these sources of energy have become increasingly privatized.

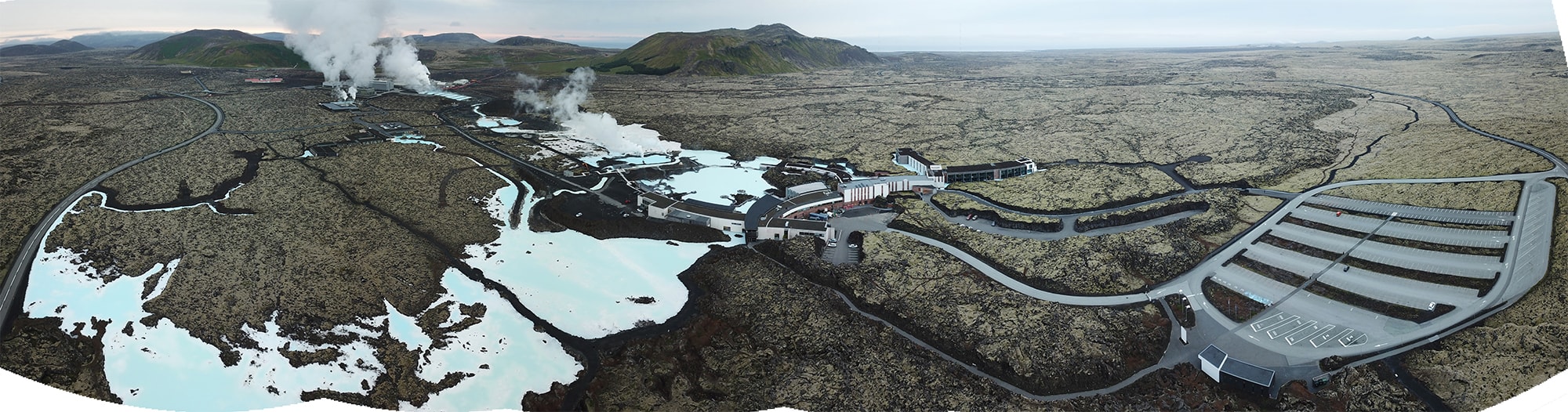

Blue Lagoon complex in foreground, with Svartsengi Geothermal Power Plant in background (July 2018). Photo by Catherine De Almeida.

In the midst of their energy crisis, the National Energy Authority in Iceland began pioneering the development of centralized, geothermal energy production networks. In 1976, the Svartsengi Geothermal Power Plant on the Reykjanes Peninsula in southwest Iceland became the first geothermal Combined Heat and Power (CHP) plant in the world setting the global standard for contemporary geothermal district heating and power production facilities [2]. The geothermal water in this region, however, cannot be directly used due to its distinctive geochemical composition. Geothermal water heats freshwater for regional distribution, while extracted steam runs turbines [3]. Svartsengi currently has an installed capacity of 75 MW for electricity production and 190 MW for heat, providing 45,000 people with electrical power and 17,000 people with hot water [4].

Svartsengi Geothermal Power Plant in foreground, with Blue Lagoon in background and to left (July 2018). Photo by Catherine De Almeida.

Processes that utilize geothermal energy create a byproduct: an output of cooler geothermal effluent [5]. In an attempt to regenerate the water table, brine effluent was released into the adjacent hardened lava-scape. Oxidation of minerals from this geothermal effluent clogged the bedrock’s pores, forming a lagoon [6]. The National Energy Authority originally described this landscape condition—a visible registration of mismanaging byproducts from renewable energy production—as an environmental disaster.

Svartsengi Geothermal Power Plant, with geothermal effluent to left of power plant (July 2018). Photo by Catherine De Almeida.

Svartsengi Geothermal Power Plant, with geothermal effluent at center (July 2018). Photo by Catherine De Almeida.

In typical Icelandic fashion, though, residents perceived the lagoon not as a disgusting byproduct from the industrial process of geothermal energy production, but as warm water to bathe in. Icelandic culture is built around bathing in warm geothermal water wherever it is found, and allowed residents to voluntarily claim this waste landscape as a commons, transforming perceptions of this landscape from undesirable byproduct into an unexpected recreational oasis. Energy and waste produced an emergent cultural landscape. Nearly a decade later in 1987, its popularity led to the construction of a modest bathhouse in order to increase public access [7]. Following capitalist pursuits, by 1999, the Blue Lagoon became further formalized with the design and construction of a complex of buildings: a spa, an R&D center, and a psoriasis clinic [8]. This formalization also privatized this waste landscape.

Geothermal effluent, with Svartsengi Geothermal Power Plant in background (July 2018). Photo by Catherine De Almeida.

Blue Lagoon Spa complex, with new hotel in background (July 2018). Photo by Catherine De Almeida

The Blue Lagoon is now considered one of 25 wonders of the world. With a unique microbial and algal ecosystem in mineral-rich water that generates silica mud (the foundation of its skin product line) [9], it is now the top tourist destination in Iceland, hosting over 1.3 million visitors in 2017 [10]. A human ecology and economy developed out of materials and conditions perceived as waste—the Blue Lagoon’s existence is intrinsically linked to the geothermal power plant.

Visitors apply silica mud, a byproduct of the geothermal effluent, to their skin (July 2018). Photo by Catherine De Almeida.

The Blue Lagoon spa complex consists of the lagoon, restaurants, steam rooms, and a newly constructed hotel (July 2018). Photo by Catherine De Almeida.

However, as the Blue Lagoon has developed over the last decade, so have its developers’ strategies for catering to tourists from cultures that perceive all industrial waste, such as from energy production, as undesirable and potentially harmful. Although the shared waste relationships between power plant and spa industry continue to exist and evolve, this negative perception has resulted in marketing and communication strategies that make these processes less legible to visitors in an attempt to choreograph a high-end, “natural” spa experience. The everyday visitor is both unaware of the Blue Lagoon’s fascinating origins and the ongoing innovative development of sharing waste—resource streams—within a shared, hybrid industrial-recreational waste space.

Recently constructed berms in background block views to the Svartsengi Geothermal Power Plant (July 2018). Photo by Catherine De Almeida.

Steam vents such as the one pictured were strategically place to use steam to block views to the Svartsengi Geothermal Power Plant (July 2018). Photo by Catherine De Almeida.

The spatial and experiential legibility of this manufactured, enviro-technical landscape has become obscured and sterilized. The textural quality of lava rock that once lined the lagoon is now submerged under a layer of concrete. Large volumes of basaltic gravel have been formed into 3-5 meter tall berms, while the strategic placement of steam vents disguise what was once a strong audible, palpable, visual connection between geothermal energy production and geothermal spa. The over-choreography of creating a high-end spa experience is akin to what some have described as a “Disney World” of spas, and is one many visitors feel no need to repeat. The exaggeration of luxuries with increased pricing has made the Blue Lagoon inaccessible, targeting a particular class of tourists. It is no longer culturally Icelandic, but culturally global. The company’s endless reconfiguration of this landscape is motivated by the constant search for how to cater to the mainstream expectations of what a spa “should be,” rather than embrace and create an authentic experience of energy and waste legibility, relinquishing the opportunities to transform pre-conceived notions that all waste is undesirable. This further perpetuates misconceptions that all wastes and industrial processes are “bad,” rather than working to change cultural attitudes toward waste by uncovering its nuances and celebrating its productive qualities.

After reconfiguring the lagoon, areas of the original lagoon were drained, as seen in the foreground of the photograph. The Blue Lagoon spa complex is in the background (July 2018). Photo by Catherine De Almeida.

Waste legibility can be an asset shared by active power generating operations, a novel ecological community, and recreational uses. In the case of the Blue Lagoon, the formalization of this wasteland commons negated a democratic space by creating a high-end, unaffordable, privatized spa industry that conceals the underlying waste reuse frameworks that created the landscape and its unique conditions. What has occurred at the Blue Lagoon parallels the overall development of Iceland’s energy infrastructure—domestic sources of renewable energy and the cultural landscapes from which they are sourced have become internationally privatized, largely through tourism and aluminum smelting. Akin to the ways in which enclosure of the commons in medieval England commodified the landscape, the Blue Lagoon has evolved to become a commodity of landscape consumption—no longer a commons of a productive wasteland, but a commodity to be consumed by global tourists. In order to meet this demand, the narrative of this waste landscape has become suppressed and made invisible in order to cater to the globalized tastes and expectations that a spa and power-generating facilities must be separated—physically through tall lava rock berms and verbally through story-telling and ad campaigns—driven by disgust instead of fascination.

Designers have the capacity to design with waste instead of against it, enabling the diversity of waste conditions to become an impetus for uncovering new, hybrid programmatic relationships (such as energy production and recreation) that intentionally register its visible characteristics—a landscape lifecycles approach. Rather than avoiding their challenging conditions, waste landscapes must be embraced as opportunities for creating productive relationships with waste as a common ground through enhancing legibility, forming hybrid assemblages in the transformation of perceived physical and spatial wastes.

Acknowledgements

The ongoing research presented in this article has been generously funded by the Penny White Travel Fellowship from Harvard University Graduate School of Design and the Layman Seed Award from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. I am indebted to everyone I have met and interviewed in Iceland over the last decade, especially Magnea Gudmundsdóttir, who provided me with a tour of the Blue Lagoon, and Hronn Arnardóttir, who provided me with information about the Blue Lagoon’s research and development.

Catherine De Almeida is an Assistant Professor of Landscape Architecture at the University of Washington. Trained as a landscape architect and building architect, her research examines the materiality and performance of waste landscapes through exploratory methods in design research and practice. Catherine received her MLA from Harvard University and her BARCH from Pratt Institute. She is a certified remote drone pilot, an Honorary Member of the Tau Sigma Delta Honor Society in Architecture and Allied Arts, and a Fellow of the Center for Great Plains Studies. Her landscape lifecycles work has been supported by numerous grants, and recognized in national and international publications and media outlets, including the Landscape Research Record, Journal of Landscape Architecture, and Journal of Architectural Education.

Catherine De Almeida is an Assistant Professor of Landscape Architecture at the University of Washington. Trained as a landscape architect and building architect, her research examines the materiality and performance of waste landscapes through exploratory methods in design research and practice. Catherine received her MLA from Harvard University and her BARCH from Pratt Institute. She is a certified remote drone pilot, an Honorary Member of the Tau Sigma Delta Honor Society in Architecture and Allied Arts, and a Fellow of the Center for Great Plains Studies. Her landscape lifecycles work has been supported by numerous grants, and recognized in national and international publications and media outlets, including the Landscape Research Record, Journal of Landscape Architecture, and Journal of Architectural Education.

Notes

[1] Orkustofnun, “Geothermal Development and Research in Iceland,” February 2010, accessed May 24, 2019, https://nea.is/media/utgafa/GD_loka.pdf, 14-16.

[2] Albert Albertsson, “Glimpse of the History of Hitaveita Sudurnesja Ltd: The Resource Park Concept,” United Nations University 30th Anniversary Workshop (2008), 1–8: 2.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Magnea Gudmundsdóttir, Ása Brynjólfsdóttir, and Albert Albertsson, “History of the Blue Lagoon in Svartsengi,” Proceedings World Geothermal Congress 2010, Bali, Indonesia (April 2010), accessed May 24, 2019, https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/2cb3/0a8cd00f2d1a0046bc81bf93354dc62a9fad.pdf, 1–6:1.

[5] Catherine De Almeida, “Performative by-products: The emergence of waste reuse strategies at the Blue Lagoon,” Journal of Landscape Architecture 13, no. 3 (2018), 64-77: 67, https://doi.org/10.1080/18626033.2018.1589142.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Blue Lagoon Ltd. (2016), Blue Lagoon Press Kit, pp. 1-5, 1.

[8] Gudmundsdóttir Brynjólfsdóttir, and Albertsson, “History of the Blue Lagoon,” 3; Albertsson, “Glimpse of the History,” 5.

[9] Gudmundsdóttir, Brynjólfsdóttir, and Albertsson, “History of the Blue Lagoon”.

[10] Hronn Arnardottir, R&D Specialist at the Blue Lagoon R&D Center, Interviewed by author, Blue Lagoon, Iceland, July 2018.

Cite

Catherine De Almeida, “The Blue Lagoon: From Waste Commons to Landscape Commodity,” Scenario Journal 07: Power, December 2019, https://scenariojournal.com/article/blue-lagoon/.