The European Union, with its ambitious targets for CO2 reductions, has become a significant force for the research and design of alternative energy technologies [1]. Many of its energy scenarios, seeking large reductions in fossil fuel use, have identified the North Sea in particular as a source of strong, regular winds and an excellent location for the future deployment of offshore wind farming on a massive scale [2],[3]. The energy ambitions of EU nations on the North Sea, however, and the need to put them on a map, effectively create overlapping national extraction territories, as multiple uses and nations compete for finite space. The push for territorial reorganization of the sea highlights the importance of cartographic representation in setting policy, as well as the gaps that still exist before dynamic and representative management of complex marine resources can be achieved.

Extracting Energy from Wind

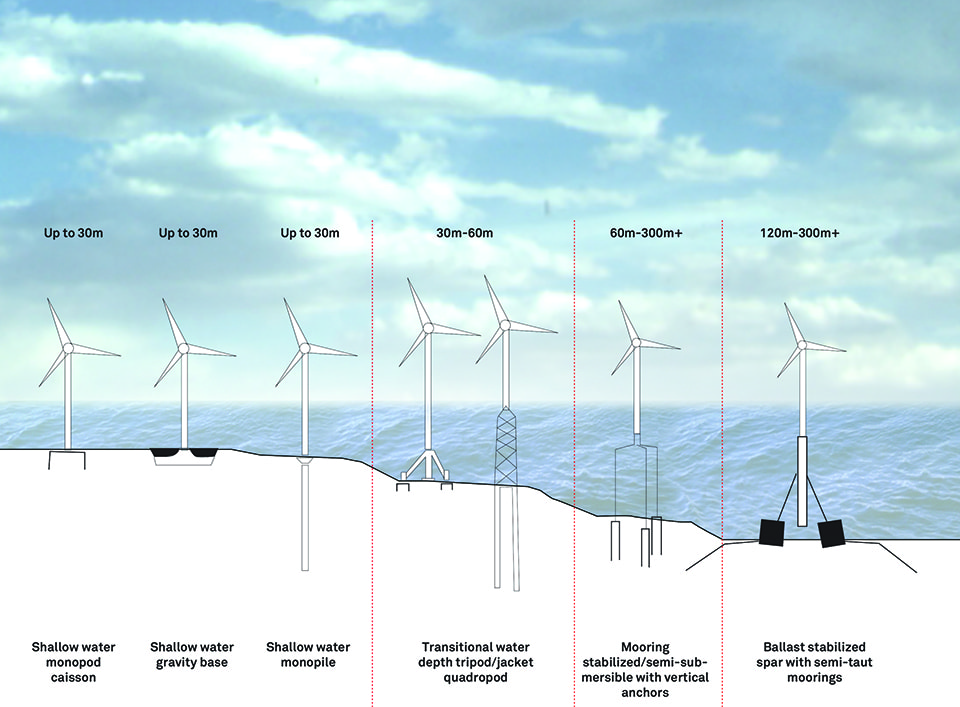

Due to the nature of its fixed, capital-intensive technologies, wind farming is a highly spatial operation. A typical offshore farm is primarily comprised of turbines arranged at a distance from one another in order to maximize wind flow; it may also require supplementary offshore energy converter platforms and buried cable networks, depending on its distance from shore [4]. In addition to the turbines, cables and platforms, there are myriad accessory technologies that go into the construction and maintenance of a wind farm, such as the specialized vessels that install turbines [5].

Offshore wind turbine types. Deepwater wind turbines are experimental.

Floating turbine types are also being developed.

Furthermore, wind farms are fixed in zones that have traditionally mixed such fluid activities as fishing, shipping, and recreation. This spatial fixity has caused conflicts and contestations, from the economic, to the ecological (the full extent of a farm’s impact on a local ecosystem is unknown), [6] to the cultural (the human objections to the visual impact of turbines is a main reason for wind farms being established offshore, and increasingly far from the coast) [7].

Spatial Fluidity and Fixity in Maritime Planning

With the shift to renewable energy technologies, writers like Timothy Mitchell [8] have identified a return to the kind of spatial fixity that existed before the discovery of fossil fuels. Just as burning wood for energy had a direct spatial impact (more energy necessitates more clearing of trees), there is a relationship between the amount of renewable energy captured and the amount and location of space taken up (now filled with large physical structures such as turbines, photovoltaic panels, etc.). Rather than contributing only to the production of ever more frictionless and dislocated electronic “flows,” large-scale renewable energy networks also create very real “places.”

Starting in the early years of this century, the EU strongly encouraged comprehensive marine planning processes that integrate wind power’s significant spatial demands with that of other actors. In large part, these policies were intended to incentivize the smooth development of electricity networks in the North Sea. The Marine Strategy Framework Directive [9] for instance, is a component of the EU Integrated Marine Policy, [10] which spells out the need for integrated, cross-sectoral management of sea-space. An even more explicit push for organized management of marine resources has come in the form of a recent focus on “Marine Spatial Planning,” directed by individual EU member states [11],[12]. This paper will look at Dutch marine spatial planning efforts in the North Sea as a case study for how the process of extracting energy out of wind in Europe leads to new and re-scaled understandings of marine territory.

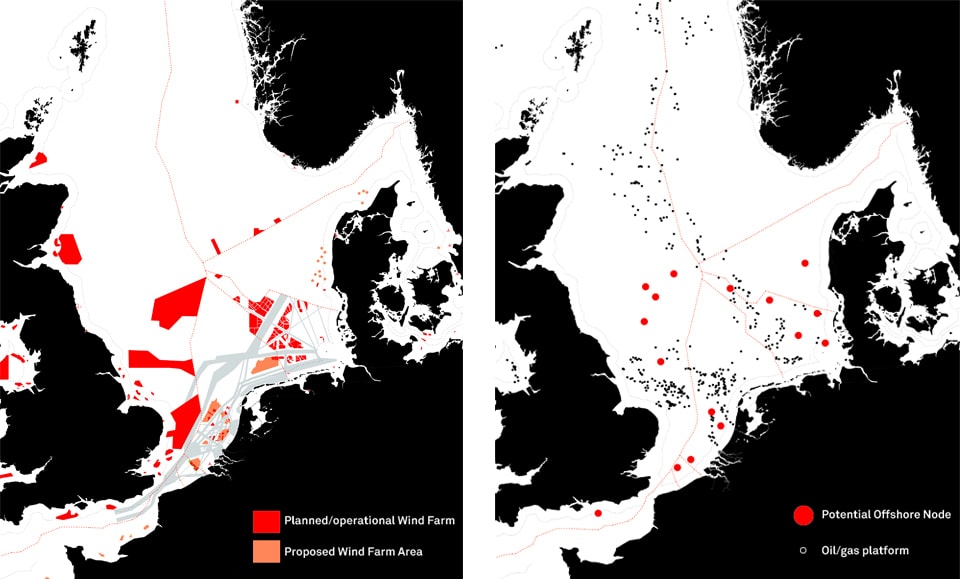

Spatial Fixity: Planned and operating wind farms in the North Sea [left];

Potential platforms [right]

“Radial” grid geometry with offshore hubs [left];

“Meshed” grid geometry with offshore hubs [right]

Data source: NSCOGI 2009 Grid Study

Sea Territory: Theoretical Lenses

The marine spatial planning paradigm is an outgrowth of steadily shifting historical conceptions of states’ control of sea territory. Amid naval jockeying by European powers, differing positions were laid out in a series of 17th-century treatises [13]. Hugo Grotius of Holland, writing in his Mare Liberum of 1609, proclaimed an absolute “freedom of the seas” — the sea as an empty, unowned space that resisted state control and was open for use by all nations. Portuguese friar Serafim de Freitas, writing in 1625, retorted that that sovereigns cannot own the sea but can control trade routes, which was reflective of the mercantilist age, where the sea was a force field for the exercise of power in order to control trade. Englishman John Selden, in his 1636 Mare Clausum, went even further by insisting that the state may directly own sea space, excluding the vessels of other nations within their national “closed seas” [14],[15].

In the 1700s, countries increasingly claimed exclusive control next to their coasts [16] while regarding the deep sea, far offshore, as a featureless transportation surface: “international waters” minimally regulated in the Grotian style. The development of offshore oil wells and deep-sea fishing, however, necessitated a resurgence of more tightly controlled marine stewardship, which was ultimately expressed in the 1994 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea III (UNCLOS III) agreement. Among other things, this regulation defined the limits of territorial waters and Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ’s), which are zones that extend 200 nautical miles from a nation’s coast in which it can exert some exclusive resource rights [17]. In a networked Europe, where the sea is simultaneously conceived of as a zone for mobility and a zone for spatially fixed investment (such as wind farming), the North Sea region is increasingly full of contradictions between Grotian, Freitan and Seldenian understandings of marine territory.

Seldenian Stewardship and the Dutch National Narrative

Offshore wind energy re-territorializes the sea through its redefinition of the sea-space of nation-states. A primary instrument in that process is the Marine Spatial Plan (MSP), which emerged directly out of spatial conflicts stemming from the expansion of wind energy. MSPs are in place in the Netherlands and Germany, and are under development in other North Sea countries; typically they result from an extensive process of negotiation with various stakeholders and are finalized in a set of maps that spatially separate zones of use, similar to a land use plan.

In the Netherlands, a 2005 document called the “Integrated Management Plan for the North Sea 2015” calls out the spatially specific zones of separated uses: recreation, coastline protection and land reclamation closest to the shore; sand extraction up to 12 miles offshore; then wind farms beyond [18]. In later documents, [19],[20] the various uses of the sea are more diverse and the multifunctional use of space is more explicit. All these documents acknowledge that shipping, sand dredging and wind farming are critical uses of the ocean [21]. Some call explicitly for “innovative synergies,” listing examples that include aquaculture combined with turbines, wind farming as tourist attractions, or the farming of seaweed on energy infrastructure [22]. The role of the MSP, then, is not to challenge existing unsustainable uses of the ocean, but to better manage existing and projected uses of marine space, especially but not exclusively having to do with wind farming.

As mentioned previously, under UNCLOS III nations have exclusive power over a 12-mile offshore zone and then additional jurisdiction over a 200-mile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). The EEZ as a newly managed space is of interest because it reflects shifting understandings of territory, with planning decisions and nuances of power becoming reconfigured and re-scaled at both the local and national level. Sociologist and spatial theorist Neil Brenner refers to re-territorialization as the “reconfiguration and re-scaling of forms of territorial organization,” a shifting which re-scales planning decisions and the nuances of power [23]. But the MSP is not simply extending modes of ‘land-based’ governance over the sea [24],[25]. Instead, it reconfigures territory within a marine context informed by the contradictory historical conceptions of the sea, from “international waters” to national ownership of the ocean.

The globalized sea is increasingly defined by these contradictions. International shipping intensifies and denaturalizes the sea into a disembodied network of container ports, but investment into renewables, deep-sea fishing, and seabed mining necessitates increasingly fixed, discrete spaces in which to invest and disinvest. Wind farming represents a new extreme of these large, spatially fixed infrastructures. The traditional Grotian stewardship model of minimal regulations over the deep seas, in light of increasing demands on ocean-space by spatially fixed investments like wind farms, is no longer adequate. The recent push to develop new stewardship mechanisms for the EEZs of the North Sea, then, reflects a shift in territorial understanding from Grotius (the “free sea”) to Selden (“territorial management”), mirroring the contradictory forces of globalization.

Seen in this light, the Dutch MSP is a model of neo-Seldenian stewardship that attempts to manage away (through spatial separation or forced multi-functionality) the conflicts between these two poles of globalized space [26]: on the one hand increased mobility (shipping and circulation), and on the other spatially fixed investments (wind farming). Rather than seeing the EEZ as a neutral, featureless “transportation surface” that enables the movement of capital from one zone to another, the new paradigm sees it as a highly managed territory which is simultaneously a “space of flows” and a place for investment. In this case, Brenner’s re-territorialized, re-scaled “second nature” arises out of the spatial fixity of wind farms, but their offshore location requires an understanding of this new territory that is rooted in multiple historical marine stewardship models.

Mapping and Visual Representation

For the Dutch government, visual representation is a crucial tool used to fold this new managed marine zone into its national territory. One document which shows this is the North Sea 2050 Spatial Agenda, which clearly outlines the priorities for the Dutch state’s treatment of the sea [27]. According to this Agenda, the North Sea is explicitly a part of the nation:

“It has again become clear that the North Sea is not just an area of water behind the dunes, but has its own opportunities and special, sometimes vulnerable qualities. The North Sea is a unique part of the Netherlands.” [28]

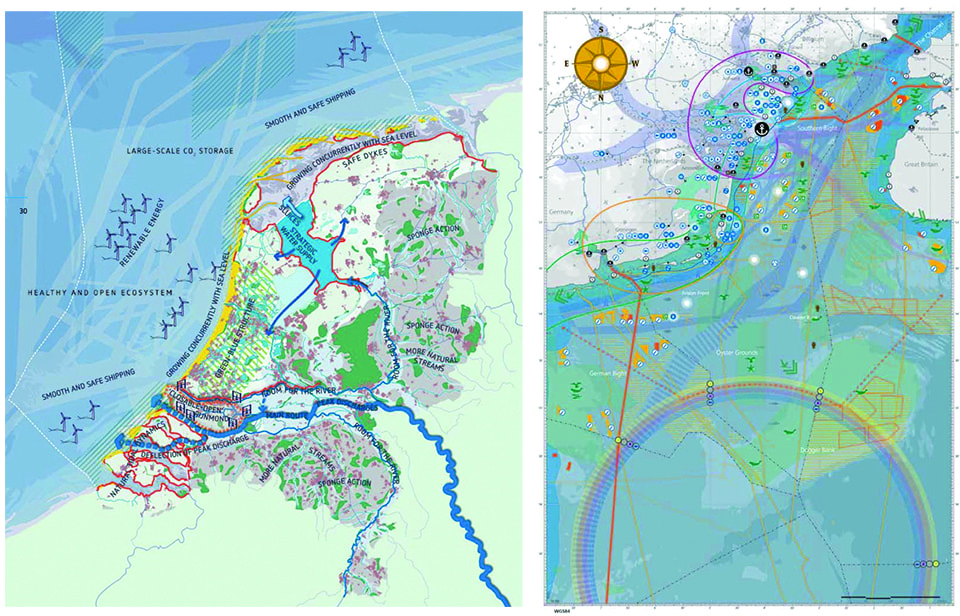

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of this document is the way in which its authors have chosen to map the issues it addresses: the drawings reverse convention and point South to the top of the page [29]. The result is a series of disorienting representations that blur the boundaries between water and land to emphasize the continuity of the Dutch territorial claim.

Netherlands & offshore zone as represented in the National Water Plan [30] [left]; Dutch North Sea as represented in the North Sea 2050 Spatial Agenda [31] [right]

The inclusion of the North Sea into the official Dutch Water Plan represents the integration of the North Sea into Dutch territory at both the official and cultural level. The history of cooperative water management in the Netherlands is a point of pride and an organizing structure that justifies and rationalizes government intervention into many aspects of private life [32]. The urgent need to “pull together” as a nation is communicated through clear, aesthetically appealing documents that present “water” as a unifying topic, which continues to shape Dutch national identity. The presence of the North Sea in the National Water Plan, then, could be seen as the final integration of this sea-space into the exhaustively planned and mapped territory of the Netherlands. Rather than an oceanic void filled with discrete, roaming territorial objects, the space of the EEZ is drawn as an extension of the nation, and by extension of the government.

Contested Territories

The electronically airy, global, and networked aspects of modern capitalism are powered by a back-end of spatially significant infrastructures, such as those of transportation, communication, and energy production. The outcomes of this contradictory dialectic between mobility and fixity will become increasingly relevant as wind energy in Europe expands under the EU’s ambitious emissions reduction goals; the North Sea, with its steady winds, is a hub in this network. The existence of spatially fixed wind energy extraction technology within what was previously considered an oceanic void has particular implications for the definition of national territory. Should the EEZ, now planned to the smallest detail, be considered an extension of the nation? While the North Sea was lightly mapped until recently, the modern shift towards increasing flows (e.g. shipping) and simultaneous spatial investment (e.g. energy extraction) has resulted in a need for a more managed sea-space and a shift to more territorialized governance in the form of Marine Spatial Planning. The MSP, in essence, represents the re-territorialization of the sea at the scale of the nation (and, ultimately, the nationalization of marine territory) through a shift from Grotian to Seldenian-style stewardship.

The process of re-territorialization at any scale, however, is neither smooth nor uncontested. Re-territorialization takes it as a given that existing conceptions of territory are being replaced, so what happens to those existing actors that operate on different temporal and spatial scales? In many cases they are simply absorbed into new models of stewardship through the managerial process. In the North Sea, existing uses such as shipping lanes, anchoring areas and wind farming zones are neatly laid out in spatial plans that assign each function its physical zone. This kind of Seldenian marine stewardship regime reflects an understanding of ocean-space which is techno-managerial and fundamentally static. The case of the fishing industry, however, provides an interesting example of an alternate spatial understanding which demonstrates the complexity of managing competing and overlapping territorial claims within the space of the sea.

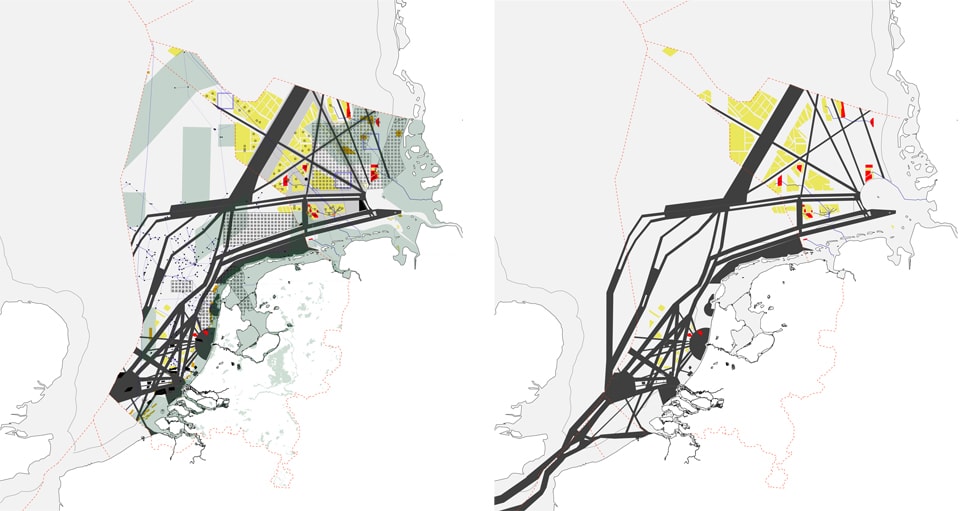

Fixity and mobility: shipping lanes in Dutch and German EEZ’s and planned/operational wind farms [right];

Territorial overlapping: Dutch and German Marine Spatial Plan elements [left]

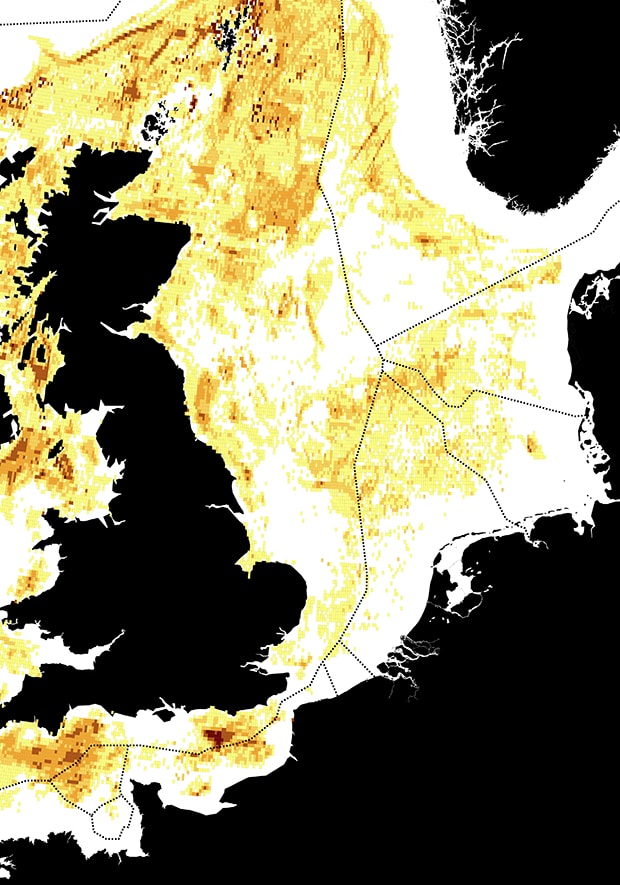

Fishing was not included within the Dutch MSP’s initial priority uses (despite its enormous importance to the regional economy). The Dutch fishing industry is managed by the hierarchical Common Fisheries Policy (CFP), which is continental, rather than national, in scale [33]. As a result, fishers have felt excluded from the process of developing the MSP; in addition, the nomadic nature of fishers leads other actors to assume that they can always “just go somewhere else” [34]. In the North Sea, fishers have been able to interface with the MSP through the North Sea Advisory Council, which has provided an intermediate level of organization below the CFP. One request made of the fishing industry is that it provides maps of its activity so that they can be included in planning considerations. The lack of these maps has been acknowledged more generally as a “cartographic silence” that threatens the agency of fishers and fishing communities [35]: essentially, if they do not make themselves visible to planners, they will not be included in decisions that affect them. For fishers, however, the act of mapping is controversial — there is a fear that through mapping they will lose control over their activities [36]. In other words, “the dynamic and heterogeneous nature of fishing activities and the resulting varying spatial needs conflict with permanent or long-term distribution of marine space for different uses” [37].

UK fishing catch, showing a territorial range that crosses political boundaries.

Data source: United Kingdom Marine Management Organization

This example raises two separate issues: first, it makes evident the existence of dynamic territorial claims to the ocean that are made by animals and the people who hunt them; and second, it demonstrates the power of representation as a tool in the definition of territory. Fish and other marine life-forms are unaware of invisible political lines drawn on maps, and there is clearly little that can be done to make them respect those boundaries. The absurdity of attempts to “manage nature” can be seen in maps of the Natura 2000 program and other ecological sites that demarcate abstract squares and rectangles in the ocean as “protected ecological zones,” while under the surface animals follow independent logics of movement, reproduction and feeding. The fishers who make their living by following these animals have an understanding of the territory of the North Sea which is not and cannot be based on political or planning boundaries.

A map of a space often serves to justify the management of that space. For fishers, the idea of mapping their movements is threatening because it raises the possibility that their own version of territory — nomadic, dynamic and determined more by the movements of fish than by invisible lines on a map — will be overruled by a management regime intent on an entirely different form of organization more akin to terrestrial planning. In the end, this is precisely what the Dutch and other national governments do through their deployment of Marine Spatial Plans, and in the Dutch case specifically through various representations of the North Sea that merge it into the dominant techno-managerial national narrative.

The case of the fishing industry demonstrates both the complex territorial overlaps that result from the application of a new planning mechanism, and the importance of representation as a tool for agency. Could forms of mapping be found that express the dynamism of fish-based territoriality, or for other non-static uses of ocean-space? Is Seldenian stewardship and the multiplication of invisible boundary lines the only answer to the question of how to negotiate between fixity and mobility within the space of the ocean?

As a spatially fixed infrastructure, the nascent wind farming industry plays a large role in questions of territorial definition at the scale of the North Sea and in terms of national boundaries — questions that cannot be avoided in an increasingly full and energy-thirsty world. New forms of marine management and conceptions of regional cohesiveness are resulting, in large part, from offshore wind farming investments. They contain within them conflicts and overlaps that stem from new understandings of marine territory, even as the process of territorial re-scaling appears from a distance to be smooth and democratically managed. Understanding this process is an important first step towards the creation of new marine territories that are multifaceted, inclusive, and dynamic.

Claudia Bode recently received a Master of Architecture from MIT, where she explored the tensions between architecture, landscape and politics; currently she is a researcher at the Urban Risk Lab at MIT as well as a design studio instructor at Northeastern University in Boston. She co-founded the Kujenga Collaborative, a research and building organization which explores strategies for (and constructs) architecture in rural Tanzania in partnership with a local nonprofit. Claudia has worked in architecture offices in Spain, Germany, the US and the Netherlands.

Claudia Bode recently received a Master of Architecture from MIT, where she explored the tensions between architecture, landscape and politics; currently she is a researcher at the Urban Risk Lab at MIT as well as a design studio instructor at Northeastern University in Boston. She co-founded the Kujenga Collaborative, a research and building organization which explores strategies for (and constructs) architecture in rural Tanzania in partnership with a local nonprofit. Claudia has worked in architecture offices in Spain, Germany, the US and the Netherlands.