Power is a broadly defined and often elusive term that has definitions within both material and immaterial systems. On the one hand, power can refer to a utility, or force harnessed and translated into work through useful objects. On the other hand, it can mean the capacity to influence, achieved directly through political interaction or indirectly through institutional mechanisms. While there has always been an entanglement between these two definitions of power, western democracies distinguish material and immaterial forms of power by segregating material power (goods and services) in the private domain, and immaterial power (the State and its institutions) in the public domain.

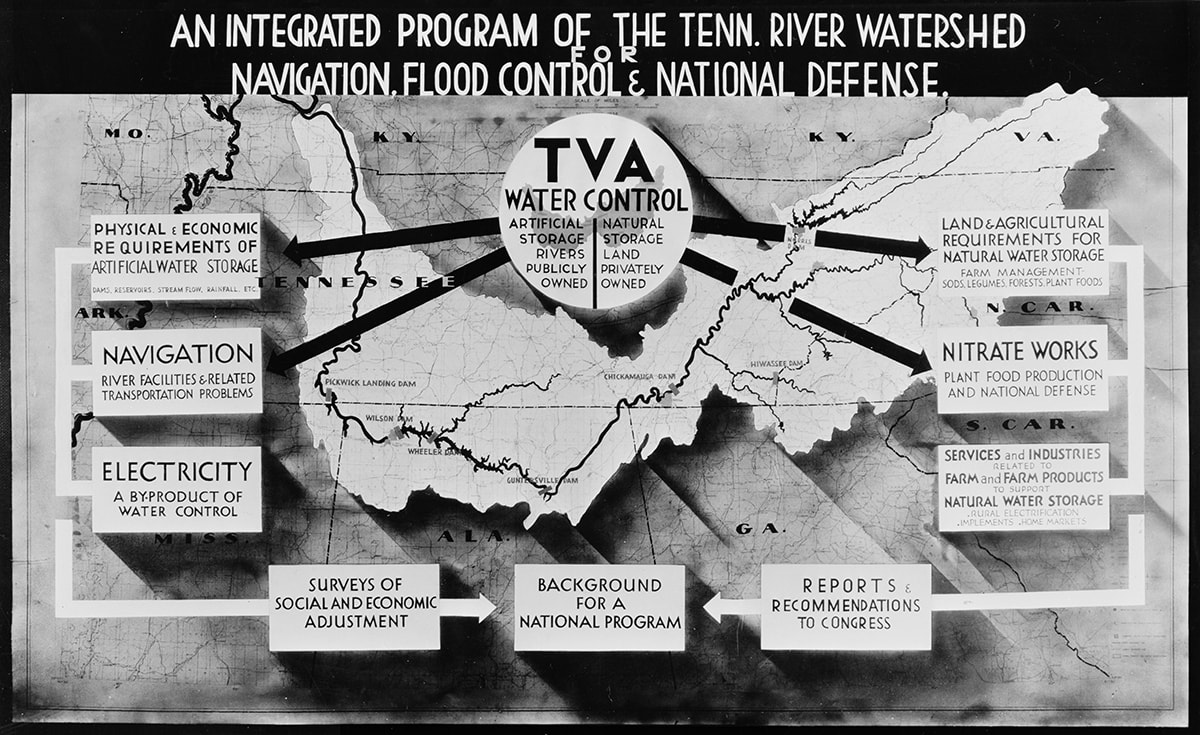

In the United States, the Tennessee Valley Authority presents a unique historical example of a federal agency in which material and immaterial power were inextricably linked to the geospatial transformation of an entire region, offering insight into the complex entanglement of objects, institutions, and geographic space.

The TVA, authorized by the U.S. Congress in 1933 and still in existence today, was responsible for the design, construction, and administration of a vast system of dams along the Tennessee River and its tributaries. Starting in the Appalachian Mountains and ending at the Ohio River in Paducah, Kentucky, the system is comprised of 29 power-generating dams spanning seven states, part of a complex and expansive geographic machine that eventually integrated all aspects of life within a system of power, infrastructure, environment, politics, and economy throughout the Tennessee River watershed. But initially, the role of the TVA was seen as fairly narrow: as stated in the TVA Act, its primary focus was on navigation and flood control for the public good along the Tennessee River.

The text of the TVA Act set out the initial scope and extent of the agency’s reach:

An Act to Improve the Navigability and to Provide for the Flood Control of the Tennessee River; to Provide for Reforestation and the Proper Use of Marginal Lands in the Tennessee Valley; to Provide for the Agricultural and Industrial Development of Said Valley; to Provide for the National Defense by the Creation of a Corporation for the Operation of Government Properties at and near Muscle Shoals in the State of Alabama, and for Other Purposes. [1]

Likely inserted without much consideration, and as perfunctory short-hand for activities that might be involved in the normal course of business, “and for Other Purposes” acquired increasing agency in the early years of the TVA’s development, anticipating the dynamic, expansive power apparatus the TVA that would come to be.

A diagram of the diverse suite of functions and activities that the TVA’s system of dams eventually came to acquire. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information, https://www.loc.gov/item/2017877279/

Though navigation was foregrounded, surplus electricity was an inescapable byproduct of the dams. With the rural population of the Tennessee Valley lagging behind the rest of the nation economically and technologically, the development of power infrastructure and pursuit of a new economic region based on power became both necessary and inevitable. However, the need for stable electricity demand went along with power generation. For the TVA, this meant electrifying farms and introducing rural households to electrical appliances in order to create a new class of consumer, integrating material and immaterial systems of power. Rather than a narrowly defined administrative body, the TVA eventually became a vastly complex geographic agent that re-shaped both the meaning of power and the practices of everyday life within a new system of objects, landscapes, and institutions.

In order to unpack the complexities between material and immaterial systems of power in relation to geographic space, this essay focuses on two inventions important to the TVA’s electrification agenda: the electrical appliance and power system maps. The discourse on geographic space and infrastructure has traditionally focused on the material conditions of geographic space, but increasingly, the role of immaterial systems such as objects and institutions are being integrated into the contemporary discourse on geographic space and infrastructure. As landscape architectural theorists Jill Desimini and Charles Waldheim note: “the trajectory of representation — of concept and context — has moved from the material and physical description of the ground toward the depiction of unseen and often immaterial fields, forces, and flows. This has resulted in an important critique of geographical determinism within design culture” [2]. Similarly, political theorist Jane Bennett, in her theory of “vital materiality,” considers both the material and immaterial, the human and non-human actors that shape a landscape of objects and their “political ecology” [3]. These two discursive trajectories might offer ways of re-evaluating the history of the TVA in terms of infrastructure and geographic space, while also allowing critical reflection on present and future conditions by which regional and even global infrastructure re-defines territory.

Electric appliances and maps of power grids appear to inhabit very different social and political configurations: appliances foreground the social territory of the home, while maps foreground the political realm of geography. This distinction, however, is quickly destabilized when one examines them not as individual objects with distinct, singular intentions, but as social and political artifacts within a shared system. While seemingly opposite in scale, the appliance and the map both collapsed geographic space, obliterating the scalar distinctions between the TVA and its customers. For the customer, the electric appliance correlated the vast scale of power infrastructure with the notion of utility; for the Authority, the map correlated the notion of utility with the geographic space of power.

The dual meaning of power and the conceptual adjacency that this double-entendre produces underwrite the discussion to follow: in both the electric appliance and the map, power is embodied in the artifact explicitly as electrical energy and as “the capacity to influence behaviors [4],” but also, implicitly, as force, flow, and potential. In this essay, I will foreground and unpack how both artifacts are distinct yet integrated object-systems, which manifest important conceptual adjacencies that re-shaped territory, human subjectivity, and the TVA itself. My examination of these two inventions — the appliance and the map — will include their material vitality as well as the socio-political contours that endow them with the capacity to re-territorialize daily life and the subjectivity of those who lived it.

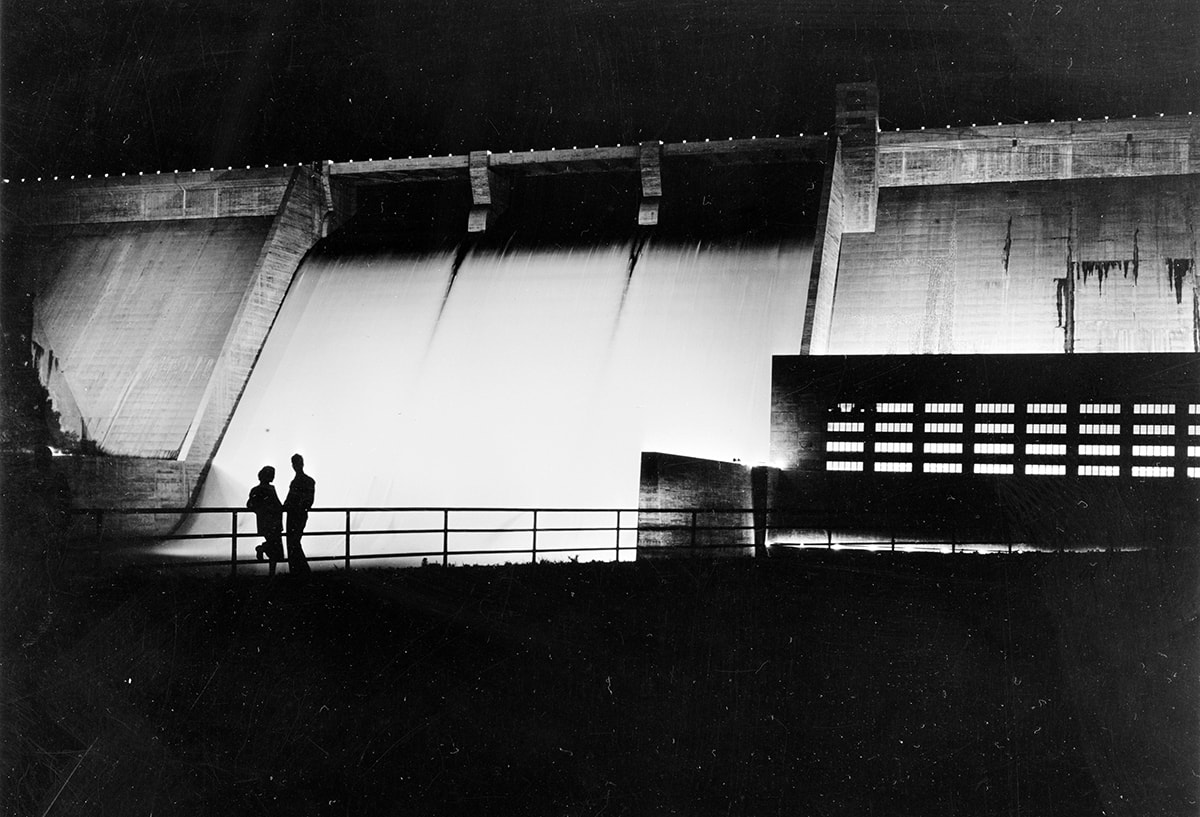

Norris Dam and powerhouse at night. Photo by Tennesseee Valley Authority (TVA). Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information, https://www.loc.gov/resource/fsa.8e00551/

In his 1980s essay, “The Grand Job of the Century,” architectural theorist Reyner Banham noted that “the TVA dams employ a vocabulary of design that occupies a unique space between regular International-Style modern . . . and the emerging Streamline shapes felt proper to the age of electro-domestic appliances” [5]. Banham’s words recall those of world-famous Swiss architect Le Corbusier’s impressions upon visiting Norris Dam in 1945. Reflecting on his visit, Le Corbusier described the dams as “generators of electrical power and monumental expressions of power” that were “facts and symbols of modern life,” [6] which are conceptualized in terms of a sublime, grand infrastructural narrative embodied in the dams themselves. Banham, on the other hand, recognized that the TVA’s grand narrative of power was distributed equally within the small-scale semantics of the home appliance. In identifying both scales of action, the appliance and the dam become co-extensive objects, operating in a unified semantic territory: the sublime landscape produced by the dams is thus reproduced within a sublime domestic landscape, while the appliance itself is both a dam in miniature and its corollary.

Norris Dam. TVA dams were not merely engineered artifacts; their aesthetic was also symbolic of the nation’s technological progress and modernity [left]. A TVA customer in Knox County. For the TVA, electro-domestics were a means of increasing demand for power and a vehicle for conveying the vocabulary of modern life [right].

Photos by Arthur Rothstein, 1942. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information. https://lccn.loc.gov/2017775157, https://lccn.loc.gov/2017832578

However, the semantic agency of electro-domestics as proxies for the TVA’s vast infrastructural landscape is only a single facet of a vast epistemological network. The viability of the Tennessee Valley as a power region relied on the TVA’s ability to articulate the utility of electricity to a rural public while also presenting it as an idea. As historian Michelle Mock states, it was not just appliances, but the whole of “the electrified, modern American kitchen took shape within a government-managed economic, social, and technological infrastructure, in which not only appliances themselves but also, and more fundamentally, home electrical service first became widely affordable and understood” [emphasis by the author] [7].

To successfully integrate electricity into the everyday lives of the Tennessee Valley’s rural public, the TVA sought to create a power economy. Rather than merely supplying any excess electricity from the dams to private utility companies, the notion of an “economy” necessitated actively expanding existing markets and generating new ones [8]. The directors of the TVA, following Fordist principles of production and consumption, sought to transform Tennessee Valley farmers into mass-consumers of electricity by making electro-domestics accessible, affordable, and pervasive in the rural home [9]. However, electro-domestic appliances that drew the most power (such as refrigerators and electric washing machines) were prohibitively expensive.

In 1926 the least expensive refrigerator manufactured by Frigidaire was priced at $468 while the median family income was just over $2000, and the prices did not drop significantly in the years leading up to the TVA Act [10]. Recognizing the cost of appliances as a major barrier to increased electrical consumption, President Roosevelt created the Electric Home and Farm Authority (EHFA) by executive order six months after the TVA Act. This new authority, which was to be managed by the TVA’s directors, would have “the powers and functions of a mortgage-loan company” [11]. The EHFA effectively acted as a financial arm for the TVA, allow it to manipulate both the supply and consumer side of appliances through the use of credit. On the consumer side, the directors of the TVA offered low-interest loans that increased farmers’ purchasing power and allowed them to buy appliances on credit. Meanwhile, on the supply side, the EHFA negotiated with major electro-domestic manufacturers to offer stripped-down, low-cost EHFA-approved models. The strategy worked remarkably well — by 1934, an approved refrigerator model manufactured by Norge Corporation retailed for $79.95 [12]. Soon after, by 1938, 60 percent of Valley households owned refrigerators (compared to less than 50 percent nationally) and 23 percent owned electric ranges (compared to 9 percent nationally) [13].

Low-interest loans offered by the Electric Home and Farm Authority made large electro-domestics like refrigerators affordable and accessible. Photo by Arthur Rothstein, 1941-1942. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017832432/

Low-interest loans offered by the Electric Home and Farm Authority made large electro-domestics like refrigerators affordable and accessible. Photo by Arthur Rothstein, 1941-1942. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017832432/

Electric appliances transformed the pace, rituals, and tasks of everyday life in The Valley. But, more insidiously, electro-domestics existed within and were inextricably linked to the creation of a credit region. Everyday life was not only altered by the utility of electricity afforded by electro-domestics, but also by the provisions of ownership and citizenship in relation to credit. In a short time, the farmer was simultaneously transformed from “agrarian” to “consumer” and “debtor” — or what Baudrillard calls the “Consumer-Citizen,” for whom credit exists as a kind of “free gift” from the “world of production” that connects the idea of choice and will, or rights, to specific objects. Once credit is introduced as an economic right, any restriction to this right is “felt to be a retaliatory measure on the part of the State [14].” Thus, credit gains a form of social power comparable to the social power of electricity: credit re-organizes patterns of use between the farmer, the appliance, and electricity. Furthermore, household objects such as appliances become absorbed within a constellation of material and immaterial socio-political actors constantly shaping meaning and identity.

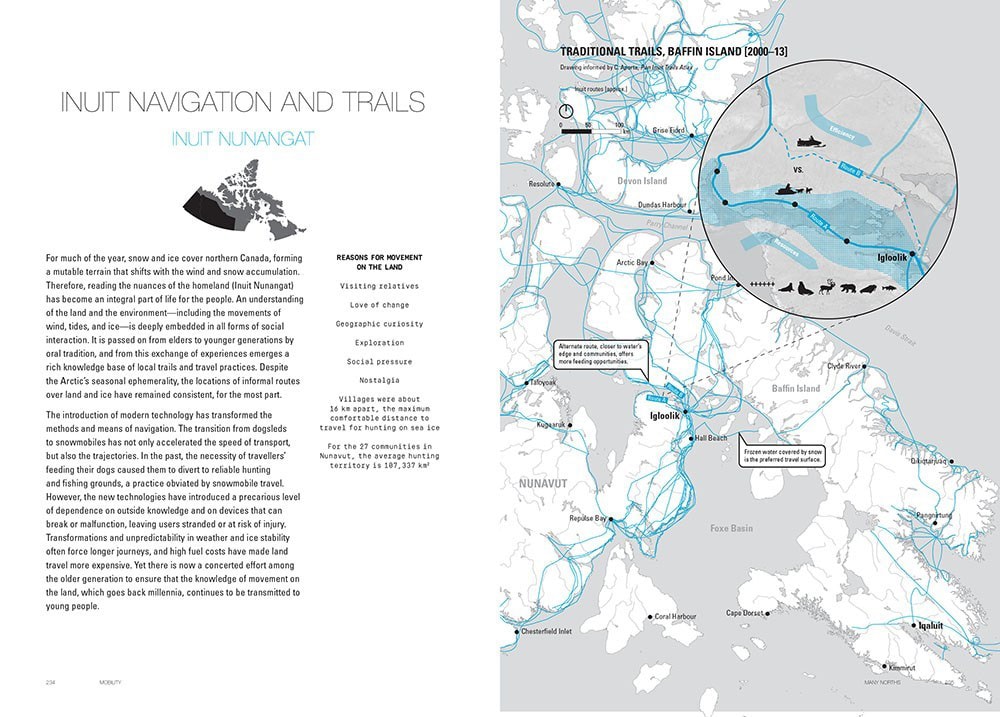

These maps were included in “Electric Power on the Farm,” a promotional publication for the Rural Electrification Administration. They represented a new connection between the geographic space of power, infrastructure, and the home. Image by The Rural Electrification Administration, “Electric Power on the Farm” (United States, 1936).

The re-territorialization of everyday rural life through credit and the electrification of the home is similarly evident in how geographic space was represented in maps produced and used by the TVA. The 1936 promotional publication Electric Power on the Farm was published in order to tell the “story of electricity, its usefulness on farms, and the movement to electrify rural America” to a broad public [15]. The publication prominently features two juxtaposed maps. On the left, “What the Countryside Shows” is an axonometric that highlights objects in a landscape, privileging illustrative space and a familiar embodied sense of the countryside. Importantly, it signifies life in a town through iconographic features that show literal connections between the home, the church, the town center, the street, electrical lines, etc., but also the rhetorical connections in the electrical grid as a system of objects that delivers utility to the domestic interior. On the right, “What Your Map Should Show” removes all pictorial figures, transforming them into graphic symbols. Here, not only does the map foreground the cartographic space of the territory it represents, but also signifies life as an abstract infrastructural space of conduits and nodes.

At first it seems odd that the map on the right would be a more desirable image of space for a rural public. Further consideration, however, reveals that by erasing life as made up of icons, the map foregrounds modernity in the form of expansion and progress. The iconographic map on the left is fixed in time and place; in contrast, the map on the right shows a dynamic system in which the possibility of new electrical lines and electrified homes suggest the expansion of the town. If homes are not thought of as objects, but as abstract, notational nodes, they can be added with ease and plugged into the grid, much like an appliance. Additionally, the map on the right, in showing the system rather than the view, is not limited to the visible; the street gives way to the circuitry of the electrical grid as a present and future condition, while the ground becomes merely a referential plane rather than a spatial determinant. By deactivating the z-axis — a primary feature of the axonometric on the left — the specific form of the town is de-emphasized in favor of the virtual space of representation itself and of the system it depicts.

While a rural farmer may not have fully grasped the nuances of this juxtaposition, they would almost certainly have recognized the map on the right as representing modernity and progress. At a subconscious level the abstracted map also de-emphasized personal property and ownership in favor of the collective citizenship of the power economy, reinforcing the notion that electrification delivers progress to everyone, and everyone stands to benefit equally.

The map, together with appliances, represented a new kind of community for the rural farmer: a community based on power infrastructure rather than the architectural space of iconic form. And while the appliance made power tangible as the work of objects, the map instrumentalized power as a form of citizenship within a cartographic space. Taken together, it is possible to describe the condition of territory constituted in the Tennessee Valley as an assemblage that was much more decentralized and irreducible than historians and theorists tend to indicate. This does not mean that the actions and transformations brought about by the TVA were any less all-encompassing. Instead, it means that they were much more convoluted and prone to the internal contradictions of the kind of vast geographic systems in which people, objects, institutions, material and immaterial things are all integrated.

While it is important to continually evaluate the past in context, it is equally important to establish forward-thinking methods of practice that define new ways in which designers and theorists might participate in a discourse on geographic space and infrastructure. As such, I would like to conclude by briefly pointing out two design research practices that deftly instrumentalize design as an analytical tool for critically engaging a public discourse on geographic space and infrastructure.

Map of the Great Lakes Region MediShed. Image courtesy of RVTR. © RVTR.

Patterns of settlement and movement in the Belcher Islands, Qikiqtaaluk Region, territory of Nunavut, Canada between 1957 and 1959. Image courtesy of Lateral Office, Toronto.

Lateral Office and RVTR are two design research collaboratives whose important contributions to discursive design culture, through mapping in particular, wrangle with the political ecology and “Other Purposes” of geographic space and infrastructure. Lateral Office’s Many Norths poignantly synthesizes the past and present of Canada’s internal colonization of The North as both a territory and an idea. Many Norths pressurizes geographic space through the collapse of experimental maps and on-the-ground narratives [16]. RVTR takes a more conceptual, yet no less impactful, approach to explicating the political ecology of territory. Their project for the Great Lakes Megaregion, Infra Eco Logi Urbanism, deploys what they call “agent-based” mapping, which conjures actors within the “Infra-” (infrared, infrasonic, infradian), the “Eco-” (ecology, economy), and the “Logi-” (logics, logistics) to describe territory [17]. Both Lateral Office and RVTR manage to overcome the tendency of geographic space to be seen as static and determinate. They destabilize our conception of geographic space and infrastructure as purely cartographic, instead elucidating territory as an emergent space in which history unfolds.

These practitioners and theorists share a concern for the global state-of-affairs after the 2008 economic crisis which re-structured global power dynamics. Power as influence, as energy, as force, as utility, etc., exists today within an inherently more complex geopolitical context, with increasingly diffuse actors taking part in how geographic space is defined. Following the 2008 crash, nations turned to extra-state mechanisms to provide development funds for infrastructure. For example, China’s “Belt and Road Initiative” has accelerated in recent years, as has the European Union’s involvement in hydroelectric projects in the Balkans. This makes it all the more pressing that design culture position itself within a discourse that situates action across scales and within emergent assemblages of objects, institutions, spaces, and events. We would also do well to pay close attention to those who, whether through academia or practice, seek to explicate the deeper, less explicit interactions that can be learned from the “Other Purposes” of past, present, and future histories in places such as Canada’s North, the Great Lakes Megaregion, and of course, the Tennessee Valley.

Micah Rutenberg is a Lecturer and Adjunct Assistant Professor of Architecture at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. He is also a former Tennessee Architecture Fellow. Micah’s research examines patterns of settlement that emerge from the dynamics of infrastructure space, capitalism, and material culture. His current project is a thematic atlas mapping the Tennessee Valley Authority’s profound transformation of geographic space in the Tennessee River watershed. Micah has previously taught at Woodbury University and Arizona State University. He holds a Master of Architecture and a Master of Science in Design Research from the University of Michigan.

Micah Rutenberg is a Lecturer and Adjunct Assistant Professor of Architecture at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. He is also a former Tennessee Architecture Fellow. Micah’s research examines patterns of settlement that emerge from the dynamics of infrastructure space, capitalism, and material culture. His current project is a thematic atlas mapping the Tennessee Valley Authority’s profound transformation of geographic space in the Tennessee River watershed. Micah has previously taught at Woodbury University and Arizona State University. He holds a Master of Architecture and a Master of Science in Design Research from the University of Michigan.

Notes

[1] “An Act to improve the navigability and to provide for the flood control of the Tennessee River; to provide for reforestation and the proper use of marginal lands in the Tennessee Valley; to provide for the agricultural and industrial development of said valley; to provide for the national defense by the creation of a corporation for the operation of Government properties at and near Muscle Shoals in the State of Alabama, and for other purposes,” May 18, 1933; Enrolled Acts and Resolutions of Congress, 1789-1996; General Records of the United States Government; Record Group 11, National Archives. https://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=false&doc=65

[2] Jill Desimini, and Charles Waldheim, Cartographic Grounds : Projecting the Landscape Imaginary (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2016); ibid.

[3] Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Duke University Press, 2009).

[4] “Power,” in Merriam-Webster (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/2019).

[5] Reyner Banham, “The Grand Job of the Century,” Habitat International 5, no. 5-6 (1980): 595.

[6] Mardges Bacon, “Le Corbusier and Postwar America: The Tva and Béton Brut,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 74, no. 1 (2015): 23.

[7] Michelle Mock, “The Electric Home and Farm Authority, “Model T Appliances,” and the Modernization of the Home Kitchen in the South,” 80 (2014).

[8] The Tennessee Valley Authority, “Annual Report of the Tennessee Valley Authority for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1936,” (Knoxville, Tennessee: The Tennessee Valley Authority, 1936).

[9] Mock, 78-79.

[10] Ibid., 74.

[11] Executive Order No. 6514, (December 19, 1933).

[12] Mock, 81-83.

[13] The Tennessee Valley Authority, “Annual Report of the Tennessee Valley Authority for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1938,” (Knoxville, Tennessee: The Tennessee Valley Authority, 1938).

[14] Baudrillard and Benedict, 156.

[15] United States. Rural Electrification Administration. and David Cushman Coyle, Electric Power on the Farm : The Story of Electricity, Its Usefulness on Farms, and the Movement to Electrify Rural America (Washington, D.C.: U.S. G.P.O., 1936).

[16] Lola Sheppard and Mason White, Many Norths: Spatial Practice in a Polar Territory (Actar Publishers, 2017).

[17] Geoffrey Thün et al., Infra Eco Logi Urbanism : A Project for the Great Lakes Megaregion (2015).

Bibliography

“An Act to Improve the Navigability and to Provide for the Flood Control of the Tennessee River; to Provide for Reforestation and the Proper Use of Marginal Lands in the Tennessee Valley; to Provide for the Agricultural and Industrial Development of Said Valley; to Provide for the National Defense by the Creation of a Corporation for the Operation of Government Properties at and near Muscle Shoals in the State of Alabama, and for Other Purposes.”. In Enrolled Acts and Resolutions of Congress, 1789-1996, edited by U.S. Congress. https://www.ourdocuments.gov/: National Archives, 1933.

Anderson, Oscar E. Refrigeration in America; a History of a New Technology and Its Impact. [Princeton]: Published for the University of Cincinnati by Princeton University Press, 1953.

Authority, The Tennessee Valley. “Annual Report of the Tennessee Valley Authority for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1936.” Knoxville, Tennessee: The Tennessee Valley Authority, 1936.

———. “Annual Report of the Tennessee Valley Authority for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1938.” Knoxville, Tennessee: The Tennessee Valley Authority, 1938.

Bacon, Mardges. “Le Corbusier and Postwar America: The Tva and Béton Brut.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 74, no. 1 (March, 2015): 13-40.

Banham, Reyner. “The Grand Job of the Century.” Habitat International 5, no. 5-6 (1981 1980): 593-99.

Baudrillard, J., and J. Benedict. The System of Objects. Verso, 1996.

Bennett, Jane. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Duke University Press, 2009.

Desimini, Jil, and Charles Waldheim. Cartographic Grounds : Projecting the Landscape Imaginary. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2016.

Mock, Michelle. “The Electric Home and Farm Authority, “Model T Appliances,” and the Modernization of the Home Kitchen in the South.” 80 (2014): 73-108.

Merriam-Webster. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/, 2019.

Executive Order No. 6514. December 19, 1933.

Sheppard, L., and M. White. Many Norths: Spatial Practice in a Polar Territory. Actar Publishers, 2017.

Thün, Geoffrey, Kathy Velikov, Colin Ripley, and Dan McTavish. Infra Eco Logi Urbanism : A Project for the Great Lakes Megaregion [in English]. 2015.

United States. Rural Electrification Administration., and David Cushman Coyle. Electric Power on the Farm: The Story of Electricity, Its Usefulness on Farms, and the Movement to Electrify Rural America. Washington, D.C.: U.S. G.P.O., 1936.

Cite

Micah Rutenberg, “The TVA, Fuzzy Spaces of Power, and Other Purposes,” Scenario Journal 07: Power, December 2019, https://scenariojournal.com/article/TVA-fuzzy-spaces/.