Over the past year, an emergent discourse of “ecological urbanism” has been proposed to more precisely describe the aspirations of an urban practice informed by environmental issues and imbued with the sensibilities associated with landscape. This most recent adjectival modifier of urbanism reveals the ongoing need for re-qualifying urban design as it attempts to describe the environmental, economic, and social conditions of the contemporary city. Equally, it acknowledges that the now well-established discourse around landscape urbanism is entering a mature phase of its development.

Landscape urbanism emerged over the past decade as a critique of the disciplinary and professional commitments of neotraditional urban design and an alternative to “New Urbanism.” The critique launched by landscape urbanism has much to do with neotraditional urban design’s perceived inability to come to terms with the rapid pace of urban change and the essentially horizontal character of contemporary urbanization across North America and much of Western Europe. It equally has to do with the inability of neotraditional urban design strategies to cope with the environmental conditions left in the wake of deindustrialization, increased calls for an ecologically informed urbanism, and the ongoing ascendancy of design culture as an aspect of urban development. The established discourse of landscape urbanism is seemingly entering a robust mature phase, at once no longer sufficiently youthful for the avant-gardist appetites of architectural culture, yet growing in global significance as its key texts and projects are translated and disseminated globally. One aspect of this maturity is that the discourse on landscape urbanism, while hardly new in architectural circles, is rapidly being absorbed into the global discourse on cities within urban design and planning.

The established discourse of landscape urbanism as chronicled here and other venues sheds interesting light on the ultimately abandoned proposal that urban design might have originally been housed in landscape architecture at Harvard. One reading of José Luis Sert’s original formulation for urban design at Harvard is that he wanted to provide a transdisciplinary space within the academy. But urban design has yet to fulfill its potential as an intersection of the design disciplines engaging with the built environment. In the wake of that unfulfilled potential, landscape urbanism proposed a critical and historically informed rereading of the environmental and social aspirations of modernist planning and its most successful models. In so doing, it proposes a potential recuperation of at least one strand of modernist planning, the one in which landscape offered the medium of urban, economic, and social order.

One particularly enduring aspect of urban design’s formation over the past quarter century has been the ongoing investment within its discourse to traditional definitions of well-defended disciplinary boundaries. This is particularly revealing for contemporary readers, since it contrasts markedly with recent tendencies toward a cross-disciplinarity within design education and professional practice in North America. Several design schools have recently dissolved departmental distinctions between architecture and landscape architecture, while others have launched specifically combined degree offerings or mixed enrollment course offerings. This shift toward shared knowledge and collaborative educational experience has come partly in response to the increasingly complex inter- and multi-disciplinary context of professional practice. And those practices have undoubtedly been shaped in response to the challenges and opportunities attendant on the contemporary metropolitan condition. In this context, urbanism has recently been modified by adding the adjective landscape or ecological.

From this perspective, the recent discourse around urban design’s histories and futures seems ambivalent toward the project of disciplinary despecialization found in so many leading schools of design. Cities, and the academic subjects they sponsor, rarely respect traditional disciplinary boundaries. In this respect, the design disciplines should not expect to be an exception, and many leading designers have called recently for a renewed transdisciplinarity between the design disciplines. Unfortunately, far too much of urban design’s relatively modest resources and attention have been directed toward arguably marginal concerns in contemporary urban culture. Among these, three points are the most obvious and vulnerable to the integrity of the urban design discipline.

First, by far the most problematic aspect of urban design has been its tendency to accommodate the reactionary cultural politics and nostalgic sentiment of “New Urbanism.” While leading design schools have tacked smartly in recent years to put some distance between themselves and the worst of this 19th-century pattern-making, far too much of urban design practice apologizes for it by blessing its urban tenets at the expense of its architectonic aspirations. This most often comes in the form of overstating the environmental and social benefits of urban density while acknowledging the relative autonomy of architectural form. I would argue that urban design ought to concentrate less attention on mythic images of a lost golden age of density and more attention on the contemporary urban conditions where most of us live and work.

Second, far too much of the main body of mainstream urban design practice has been concerned with the crafting of “look and feel” of environments for destination consumption by the wealthy. Many have called for urban design to move beyond its implicit bias in favor of Manhattanism and its predisposition toward density and elitist enclaves explicitly understood as furnishings for luxury lifestyle.

Finally, urban design’s historic role of interlocutor between the design disciplines and planning has been too invested in public policy and process as a surrogate for the social. While the recent recuperation of urban planning within schools of design has been an important and long overdue correction, it has the potential to overcompensate. The danger here is not that design will be swamped with literate and topical scholarship on cities, but that planning programs and their faculties run the risk of reconstructing themselves as insular enterprises concerned with public policy and urban jurisprudence to the exclusion of design and contemporary culture.

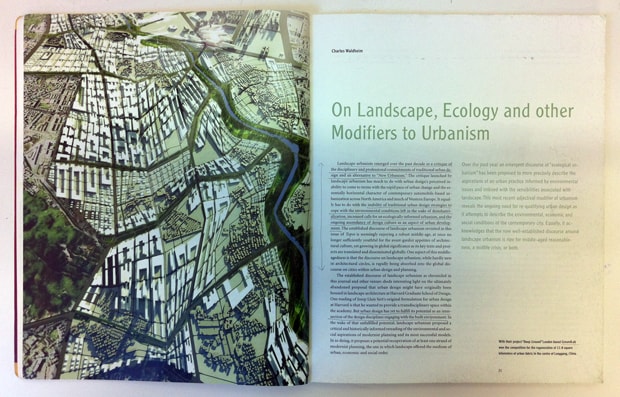

It is in the contexts of urban design’s as yet unrealized promise and potential that landscape urbanism has emerged in the past decade. Landscape urbanism has come to stand as an alternative within the broad base of urban design historically defined. Incorporating continuity with the aspirations of an ecologically informed planning practice, landscape urbanism has been equally informed by high design culture, contemporary modes of urban development, and the complexity of public-private partnerships. While it may be true, as has been recently argued, that the urban form proposed by landscape urbanism has not yet fully formed, it would be equally fair to say that landscape urbanism remains the most promising alternative available to urban design’s formation for the coming decades. This is in no small part due to the fact that landscape urbanism offers a culturally leavened, ecologically literate, and economically viable model for contemporary urbanization as an alternative to urban design’s ongoing nostalgia for traditional urban forms. Evidence of this is found in the number of internationally prominent landscape architects who have been retained as lead designers of large-scale urban development proposals in which landscape offers ecological function, cultural authority, and brand identity. Further evidence is found in the fact that many promising young urbanists have explicitly embraced a landscape urbanist agenda. This increasingly global recognition reveals landscape urbanism’s impact on a generation of professionals shaped by the tenets of an adjectivally modified urbanism, be it landscape urbanism, ecological urbanism, or whatever supersedes those two.

In his introduction to the Ecological Urbanism conference, Mohsen Mostafavi described the subject of the conference as simultaneously a critique of and a continuation by other terms of the discourse around landscape urbanism. (note 1) Ecological urbanism, just as the landscape urbanism discourse did a decade ago, aspires to multiply the thinking on cities to include environmental and ecological concepts and to expand traditional disciplinary and professional frameworks for describing those urban conditions. As a critique of the landscape urbanist discourse, ecological urbanism promises to render that decade old discourse more specific to ecological, economic, and social conditions of the contemporary city.

Mostafavi’s introduction to the topic suggested that ecological urbanism “ … implied the ‘projective’ potential of the design disciplines to render alternative future scenarios.” He further indicated that those alternative futures might place us in various “spaces of disagreement.” These spaces of disagreement span across a range of disciplinary and professional borders. Any serious attempt to examine those spaces must begin with the acknowledgement that the challenges of the contemporary city rarely respect traditional disciplinary boundaries.

In reading the new language proposed by the ecological urbanism initiative, the subtitle of the conference itself “Alternative and Sustainable Cities of the Future” indicates the linguistic cul-de-sac of contemporary urbanism, constructed around a false choice between critical cultural relevance on the one hand, and environmental survival on the other. The conference title and subtitle further signify disciplinary fault lines between the well-established discourse on sustainability and the long tradition of using urban projections as descriptions of the contemporary conditions for urban culture.

This suggests that ecological urbanism might reanimate discussions of sustainability with political, social, cultural, and critical potential. This is particularly apt as contemporary discussions of the city reveal a profound disjunction in which environmental health and design culture are opposed, a condition in which ecological function, social justice, and cultural literacy are perceived as mutually exclusive. This disjunction of concerns has led to a condition in which design culture is depoliticized, distanced from the empirical and objective conditions of urban life, while at the same historical moment, increased calls for environmental remediation, ecological health, and biodiversity suggest the potential for reimagining urban futures. One result of this disjunction has been that we are forced to choose between environmental health, social justice, or cultural relevance.

It is no coincidence that an adjectivally modified form of urbanism (be it landscape, ecological, or other) has emerged as the most robust and fully formed critique of urban design over the recent past. The structural conditions necessitating an environmentally modified urbanism emerged precisely at the moment when European models of urban density, centrality, and legibility of urban form appear increasingly remote and when most of us live and work in environments more suburban than urban, more vegetal than architectonic, more infrastructural than enclosed. I believe that these structural conditions for urban practice and the disciplinary realignments attendant to them will persist, as our language morphs and transforms in an ultimately incomplete, yet completely necessary attempt to describe them.

A version of this article was originally published in Topos 71: Landscape Urbanism; it is reprinted here with permission from the author.

Charles Waldheim is John E. Irving Professor and Chair of Landscape Architecture at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design. He coined the term “landscape urbanism” in 1996 to describe emergent practices at the intersection of urban design and landscape architecture.

Charles Waldheim is John E. Irving Professor and Chair of Landscape Architecture at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design. He coined the term “landscape urbanism” in 1996 to describe emergent practices at the intersection of urban design and landscape architecture.