Cities have extraordinary urban densities that require both strategic and sensitive systems for resource use, transit, food production, water quality, and waste management. With over half the world’s population living in urbanized areas, cities like London, Shanghai, New York City, and Los Angeles burst at the seams with an average of 10,000 to 30,000 people per square mile (note 1). In comparison to population densities across the United States, this number diminishes to eighty-seven people (note 2). The difference between eighty-seven and 30,000 people per square mile has major ramifications for the quality of life and the quality of the environment.

Early in his career, world-renowned scientist and ecologist H.T. Odum developed theories on the carrying capacity of land—the ability of land to sustain human populations over time—and laid out quantifiable standards, still in use today, for how city planners and landscape architects design for urban growth. Los Angeles’ true carrying capacity, for instance, not including aqueducts and other imported resources, equates to 200,000 people for the entire city—roughly 1% of its current population (note 3). With this stark discrepancy in mind, how we design and plan urban areas—now holding the majority of the world’s population—needs to be re-evaluated.

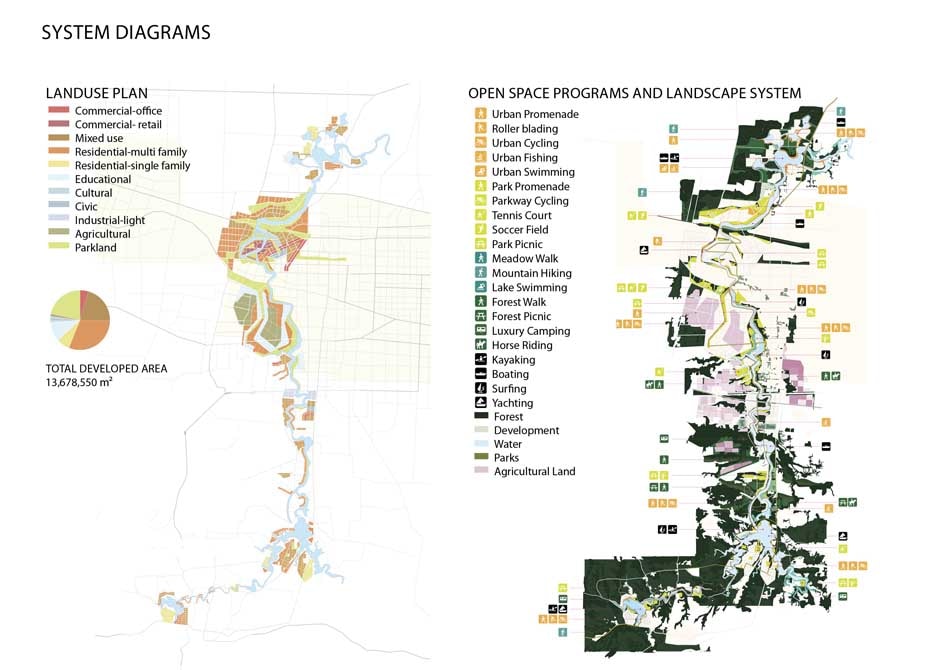

XinYang Suo River Comprehensive Plan, SWA Group

Words

A key consideration lies in how these ideas and strategies for urbanism are communicated—verbally and graphically. Defining what urbanism means is a good start. Urbanism and its many derivatives—new urbanism (Duany), ecological urbanism (Mohstaven) everyday urbanism (Chase), and Mayne’s recent entry, combinatory urbanism—while all slightly different in focus, each share a common goal of addressing the challenges of urban densities. (Please see, for instance, 60 modifiers to urbanism.) Among these terms, of course, is landscape urbanism: an idea that landscape and urban processes are inseparable; that we must look at the landscapes in our cities and the landscapes of our cities.

Purely semantics? Maybe. Conjecture? Possibly. Worth talking about? Absolutely. The study of cities needs to include many points of view in order to move beyond outmoded planning diagrams that no longer describe how to improve our cities. Despite so many variables, each of these terms argues for an ideas-rich platform for public debate, competition, and academic research in which the specificity of a particular factor can be magnified, examined, and explored in context.

“The study of cities needs to include many points of view in order to move beyond outmoded planning diagrams that no longer describe how to improve our cities.”

Diagrams: Land use and landscape open space,

XinYang Suo River Comprehensive Plan, SWA Group

Images

Understanding urbanism goes beyond theory and words, however. The collective visualization of our world—through imagery and visual representation of built and unbuilt projects in our everyday environments—is even more important in influencing how we understand and think about urbanism and landscape.

Due to the recent urban population explosions, we must begin to re-see our cities and systems and contextualize them within the larger landscape and its dynamics. At the same time, we are challenged to communicate our ideas in such a way that accurately represents proposals that offer adaptation and refinement to these volatile social and ecological conditions.

Because many of our projects are often without precedent—building entirely new stormwater retention systems; utilizing processes of bioremediation; re-programming existing infrastructure—we rely on visual representation to communicate our ideas of a better urbanism. The ability of landscape architects to communicate a set of design intentions is critical to gaining public acceptance, client approval, and, ultimately, building new places and inserting new ideas into our existing urban fabrics.

Furthermore, the issues addressed by urban designers and planners are so complex that the process of communicating ideas to the general public, city agencies, and stakeholders requires much more than a drawing. To this end, many landscape architects and planners are pulled to the re-representation model of visual reasoning.

As described by Rikva Oxman, understanding design proposals requires both cognitive knowledge and visual literacy. Oxman’s research explores how emergence, or the way complex systems arise out of relatively simple connections, informs creativity and, particularly, the process of design. Design then can be understood as a culmination of thousands of decisions—and each representation offers a layer of meaning behind these complex ideas. Our drawings and words are tools to communicate these ideas. The model of re-representation takes familiar planning diagrams and overlays them with adaptations or manipulations to reveal new relationships and possibilities for design proposals.

Buffalo Bayou, SWA Group.

Places

I want to argue, however, that there exists something more important than just words and visuals —that is, actual places. The collective images of the city and its components are created by the experience of real places in the real world. When communicating with the general public, we reference built projects and places as case studies to explain and bolster our visions.

For example, when a planner presents an image of “Main Street, USA” to a community group, everyone immediately draws upon their collective memory of what that is—small scale retail shops, promenading, benches, shade trees, festive banners, intimate street lights, dogs, and vibrant sidewalk activity. An image of Main Street is the basis of many new towns built around the world in the past twenty years.

Landscape architecture, however, suffers from a poor collective visual vocabulary. The absence of prevalent and progressive design precedents hinders our ability to communicate our ideals for a better urbanism to a broader audience. While it was once suitable to show an image of Central Park in New York City to communicate the program of a park, we are now in search of examples that can represent and meet the new challenges our cities are facing. Certainly, a few of these kinds of landscapes exist, but they are not as widespread as picturesque parks and gardens and, therefore, not as common to the general public for reference.

A more challenging example than “Main Street” is one that attempts to address ecological systems within the city. How does one visualize nature in the city? How does one convince the public that ecological cycles are needed in the urban context? What is the sales pitch? Are there examples for dynamic (and hidden or invisible) landscapes and ecological processes within urban life?

“Landscape architects, planners, and urbanists need built precedents to demonstrate that a more integrated approach to landscape and urbanism is possible.”

Using associative thinking is natural to how we represent and interpret a new situation, allowing for new ideas to step forward and grow (note 4). Yet, if new possibilities for landscape in the urban context remain unfamiliar or cognitively impenetrable, how are communities expected to endorse plans proposing integrated ecologies within busy streets and dense housing? How do we convince the public to do what has not yet been done before?

The answer: build them. Educate through practice. Landscape architects, planners, and urbanists need built precedents to demonstrate that a more integrated approach to landscape and urbanism is possible. Policy and planning does not spark a collective re-imagination of our future in the way that tangible, built work does.

Even in the midst of a global economic downturn, designers have steadily been working towards a better urbanism, pushing forward a collection of new projects that are starting to gain public recognition. Cities like Detroit spark intense debate in the possibilities that landscape urbanism offers; the High Line and Academy of Sciences are two glamour projects that add to our collective vocabulary. Perhaps the recently built Buffalo Bayou, the Anning River master plan, or the future London post-Olympic legacy landscape afford fresh views for how people, ecology, transit, and open space can co-exist. Over the next decade, as the work communicated in words and pictures transforms into real places in the world, the public understanding of both urbanism and landscape architecture will expand, while new challenges and opportunities emerge for designers to tackle.

Gerdo Aquino is the President of SWA Group and an adjunct associate professor of the Master of Landscape Architecture program at the University of Southern California. As an academic and practitioner, he seeks to promote landscape infrastructure through both research and large-scale commissioned projects. He’s also the coauthor of the book Landscape Infrastructure.

Gerdo Aquino is the President of SWA Group and an adjunct associate professor of the Master of Landscape Architecture program at the University of Southern California. As an academic and practitioner, he seeks to promote landscape infrastructure through both research and large-scale commissioned projects. He’s also the coauthor of the book Landscape Infrastructure.