Whether designing a building, operating on a patient, or cooking a meal, the tools of the trade leave their marks on the tradesman’s product. Take, for instance, the orbs and halos produced by flash photography, the lens flares resulting from aiming a camera into the sun, or the pixels of a digital image: in each example, the technologies of image creation (cameras) are indelibly imprinted onto the final output (photographs). As technologies advance, outputs change. For centuries, buildings were ornamented extrusions of simple geometric forms, surgeons relied on blades and sutures, and chefs chopped, pureed, baked, and sautéed. Today, technology has profoundly altered traditional methods. Digital modeling and fabrication techniques have enabled architects to build nearly any conceivable form with nearly any material. Nanotechnology and robotics have enabled surgeons to work with a degree of precision previously the stuff of science fiction. And chefs specializing in molecular gastronomy are utilizing high-tech lab equipment to serve up foams, spheres, and even flavored air.

Barcelona Botanical Garden designed by Carlos Ferrater and Bet Figueras.

Image credit: Alejo Bagué. From here.

But what physical impact does rapid technological progress leave on the products and processes it enables? In other words, what are the tooling marks of the digital age? Buildings with intelligent control systems, surgical scars reduced to millimeters through laproscopic technology, and high-tech food—whether haute cuisine or processed foodstuff—are obvious examples. In photography, the lens flares, orbs, halos, and pixels that were once considered a nuisance, to be avoided or removed through post-production, eventually found a following among photographers who learned to control their appearance and harness them for the emotional and ephemeral qualities they evoked. The advent of photography software has transported the shortcomings of analog equipment into fine-tuned, intentional effects, evidenced today by the soaring popularity of iPhone applications such as Hipstamatic and Instagram, which mimic the desaturated palette of Kodachrome, the shadowed corners of a Holga lens, or the yellowing edges of vintage film papers.

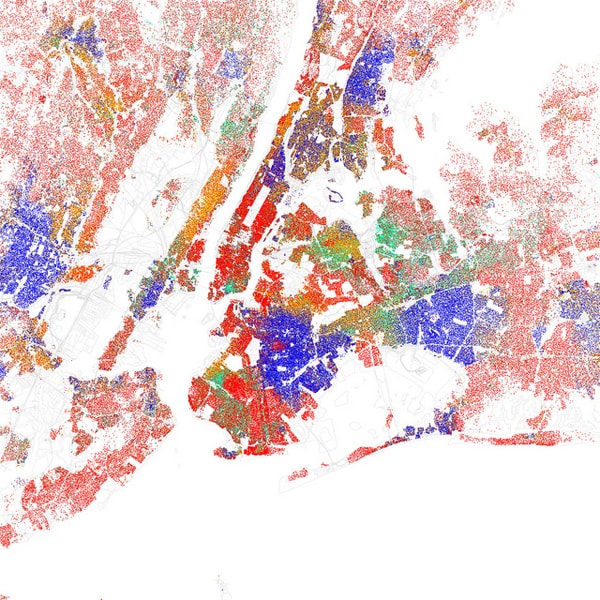

The harnessing of procedural artifacts in photography translates well to the current treatment of digital media in landscape architecture. The advent of landscape urbanism, with its roots in mid-century movements in ecology and modernist planning (note 1), has, for the most part, freed landscape architects from the postmodern tradition of steeping projects in the signs and syntax of Western European garden tradition. While pre-millennial landscapes by Peter Walker, George Hargreaves, and Martha Schwartz Partners, among others, are imbued with social, historic, or stylistic semiotics in the vein of Bryson (note 2) or Venturi (note 3)—as exemplified by Schwartz’s Jacob Javits Plaza in New York (1997) and its signifiers of the formal French garden (note 4)—the Downsview Park (1999) and Fresh Kills (2001) competitions produced a profound paradigm shift by switching the focus to ecology. Following these competitions, contextual reference in landscape today generally points to a territorial, rather than formal, context: the natural and engineered systems that activate a site and give it character. Given that one of the prime motives of digital technology is to simulate and analyze the complex regional processes that affect local sites, it makes sense that there is a desire to leave visual traces of said technology on the built landscape, as doing so is a way of revealing evidence of larger contexts and hidden systems.

Barcelona Botanical Garden designed by Carlos Ferrater and Bet Figueras. From Google Maps.

Toolmarks: A History

As tools and techniques for simulation and design have aided a transition from landscapes rooted in historic formalism to landscapes centered on ecological and social performance, the resultant “toolmarks”—vestiges of the methods used to design these landscapes—have likewise changed. Indeed, over the centuries that spacemaking has been documented, technological developments have been instrumental in shaping the types of spaces that have been built, whether intentionally or not. Laurie Olin states this simply: “if you can’t draw something, you probably can’t make it.” (note 5)

With the exception of a handful of ancient anomalies that leave historians scratching their heads—crop circles, Stonehenge, various mounds and sacred landscapes by indigenous peoples, for example—Olin’s maxim has held true in landscape architecture as it has evolved from sacred prehistoric traditions into capricious landscape painting, aristocratic garden design, and finally its chameleonic present. Today, landscape architects are trained to be equally comfortable at scales ranging from residential gardens and pocket parks to urban infrastructure networks and regional ecological mosaics. In a parallel evolution, the primary medium in which landscape architects work has shifted from earth, to paper, to screen.

The gradual transition from paper to screen has been marked by several technology-induced milestones. Prior to the industrial revolution, the field-based approach of skilled craftsmen and master-and-apprentice workshops meant that garden-making required minimal design documentation, with scale-less field sketches being far easier and faster to make than plan and section projections. (note 6) In the 16th and 17th centuries, with the notable exception of Capability Brown, plans and constructed drawings were more often used to document landscapes after they were built than to aid in the actual design of the gardens: one example of this being the aerial perspective woodcuts used to document French and Italian villa gardens that were highly prized among the social elite. (note 7) In the late 18th century, Humphry Repton popularized the design drawing as marketing tool. Repton’s Red Books employed cleverly manufactured “before and after” overlays in which anemic sites were magically transformed into bucolic scenes by simply flipping the page. (note 8)

In the late 19th century, mechanical reproduction became a viable process and landscape architecture emerged as a profession separate from landscape gardening. Subsequent increases in scope and scale mandated a standardization of the general process of making landscape drawings: measured plan and elevation projections, cross sections, and material specifications began to surpass the role of on-site fieldwork. In the 20th century, seminal landscapes of the modern period—Dan Kiley’s Miller Garden, Thomas Church’s Donnell Garden, among others—were defined by a geometric vocabulary that was constrained by the tools used to design them—straight-edge, compass, protractor, French curve. Echoing parallel movements in art and architecture, geometric formalism dominated landscape architecture through the middle of the century: it appeared everywhere from Dan Kiley’s vegetal grids to Eckbo’s palm allees. In landform, technical drawing was apparent in the artful nod to the invention of contours evidenced by Lawrence Halprin’s Lovejoy Plaza, whose terracing so faithfully adheres to its contour plan as to treat the mathematics of grading with a kind of reverence.

Detail of topographic model for Guadelupe River Park, Hargreaves Associates, 1988-1990.

Image Credit: Collection of the Frances Loeb Library, Harvard Design School.

It was through landform that landscape architecture began to make its most direct transition from paper to screen. In the early 1980s, Hargreaves Associates began using a sandbox to model its signature earthworks at the suggestion of the artist Douglas Hollis, who collaborated on the firm’s Candlestick Point park project. (note 9) What began as an experiment rapidly became a critical step in the firm’s design process. Over time, sand was replaced by clay, and a clay-modeling workshop became a rite of passage for students at the Harvard Graduate School of Design during Hargreaves’ tenure as chair of the landscape architecture program. The iterative nature of clay modeling combined with its honesty to the “real” medium of landscape—earth—foreshadowed the omnipresence of 3D modeling as a means of testing landform permutations prior to construction. It is only recently, however, through digital fabrication and advanced material mapping, that these digital models are approaching the tactility and hand-worked qualities of their clay predecessors.

CAD systems for producing projected drawings—plans, sections, and elevations—also have their antecedents in pre-digital landscapes. In marked contrast to the curves in Thomas Church’s Donnell Garden, which are compound arcs that can be constructed with only a compass and straight-edge, the whimsical tropical gardens designed by Roberto Burle Marx in the 1950s and 1960s are characterized by freeform curves that are nearly impossible to replicate accurately by hand. This looseness is perhaps foretold by Burle Marx’s use of paint, rather than drafting ink, in his plans. To facilitate the continued use of freeform curves in a more constructed manner, designers turned to computers. In 1960, MIT’s Lincoln Laboratory produced SKETCHPAD, the first computer-driven drafting system. (note 10) SKETCHPAD and other computer-aided drafting systems rapidly calculated polynomial equations for freeform curves—or more technically, splines, so named for the flexible tools used to construct curves in analog drafting, especially for shipbuilding. (note 11) Given that straight lines are rarely found in nature, the digital mastery of curves has had a profound impact on landscape design: whereas formerly, landscapes manipulated or were situated in opposition to natural forms—think French gardens with their symmetry and formal vegetation, or the orthogonal landscapes of Dan Kiley or Peter Walker—landscapes today increasingly employ the geometry of nature—curves, tributaries, gradients—to seamlessly blend into their natural settings or reintroduce nature into an urban setting.

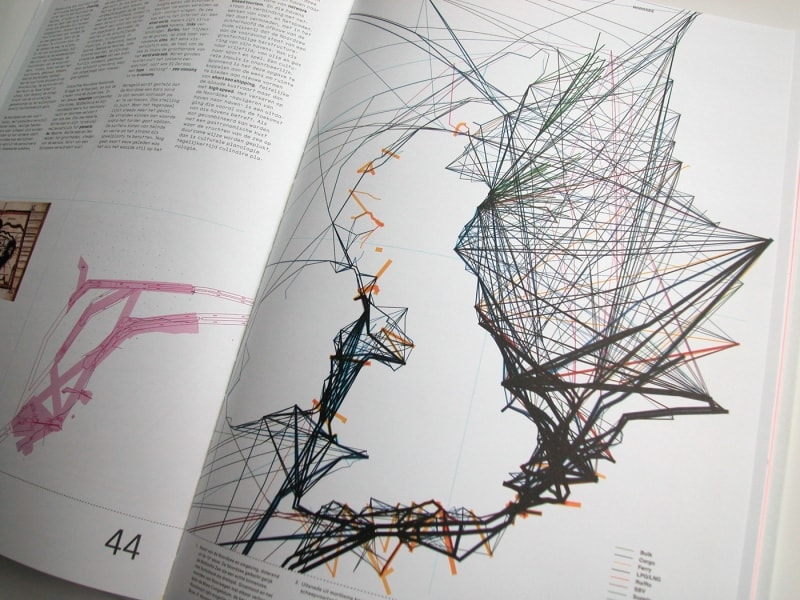

Beyond replicating the complex forms of nature, today’s digital processes have advanced to the point of accurately simulating large-scale ecological processes as well as realizing complex conceptual designs in built form. The parallel development of geodesign tools, environmental simulation software, BIM (Building Information Modeling), a variety of parametric engines (note 12), and advancements in digital fabrication have heightened the ability of landscape architects to engage at a high level in discourse previously the realm of experts in other disciplines. In landscape, the fields of biology, geology, and hydrology inform ecologically sound strategies, while engineering and architecture inform the construction of pre-fabricated elements, infrastructural systems, and complex earthworks.

Much has been written on the impact of design and fabrication technology on architecture. Indeed, a discussion of the expanded universe of employable geometry would be incomplete without referencing William Mitchell’s shape economies. (note 13) In architecture, the notion of economies of shape—progressing from the simple forms enabled by traditional drafting instruments to the limitless library of complex curves and patterns that have been unlocked by computers—largely provokes a discussion of formal typologies. Generally, when function enters the equation, it has yet to move beyond the novel tectonics of structural systems and building skins—and as much emphasis is placed on ornament as performance. Does the lack of structural economy seen in works by Zaha Hadid, or the elaborate articulation of facades seen in projects such as Jean Nouvel’s Institut du Monde Arabe, have a strong enough performative argument to justify the monumental cost of construction, or are they merely formally interesting?

Performance is a major factor that separates landscape architecture from architecture, and similarly digital relics, at their most effective, weave their way into landscape performatively, not formally. Let us return for a moment to Laurie Olin’s refrain: we can only build what we can draw. The fact that today we can draw just about anything has enormous implications for the built landscape, and requires enormous restraint by the landscape architect to ensure that technology is employed to appropriate means. Agency certainly comes into play when one considers that computers are increasingly the workhorses in both design and construction. However, a more interesting issue is that some aspects of the landscape are inherently undrawable. (note 14) Landscape is defined by expansive, indefinite spatiality; living materials that grow, weather, and decay; and temporal cycles that span hours, days, seasons, and epochs. (note 15) In consideration of these ephemera, which distinguish landscape from any other form of spatial practice, how can digital tools be harnessed to understand, manipulate, and emphasize qualities that are, by their very nature, constantly in flux? The following catalog of procedural artifacts—a sampling of the ways in which digital media activates and marks landscape today—attempts to answer this question by evaluating digital design methods for their ability to engage spatiality, temporality, and materiality, in an effort to underscore the criticality of environmental and social performance in contemporary landscape architecture.

Barcelona Botanical Garden designed by Carlos Ferrater and Bet Figueras.

Image credit: Alejo Bagué. From here.

Digital Relics in Landscape Architecture: A Catalog

Faceting

One of the most common digital artifacts in both landscape and architecture is the faceted surface. Arising, like the spline, as a mathematical approximation of complex curvature in CAD software, the faceted mesh is to a curved surface as a multi-sided polygon is to a circle. By manipulating the degree of triangulation, meshes can approach smoothness, or appear jagged or angular. It is this angular quality of a faceted mesh—a low-resolution analog of a high-resolution surface—that has fascinated digitally-inclined designers of late. Faceted surfaces, more perhaps than any other digital artifact, are direct results of the software in which they are designed. A common cross-pollinator between geographic analysis and landscape design is the TIN, or Triangulated Irregular Network: a tessellated surface formed between geographic coordinates in GIS (Geographic Information Software) that can be exported and manipulated in 3D modeling software. Because they require little memory, meshes are the native format in many 3D modelers commonly used today. To display smooth results, coarse angular meshes can be automatically subdivided many times over. The fact that users can easily toggle between smooth and angular modes with a single keystroke is perhaps responsible for a generation of young designers who view landform more easily in three-dimensional space than in plan or section: it is now exceedingly simple to think as a computer does, abstracting nearly any form into a wireframe structure or a faceted planar surface.

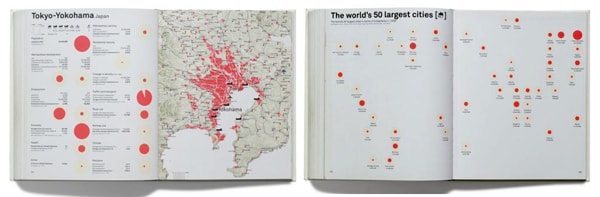

Examples of the faceted landform are increasingly prevalent, particularly among architect-designed landscape projects (Foreign Office Architects’ La Gavia Park, Herzog and de Meuron and Vogt Landschaftsarkitecten’s Laban Dance Center) and among Spanish designers (RCR Arquitectos, Vicente Guallart)—the latter of whom were doubtless inspired by one of the earliest examples of the faceted planar landform, the Barcelona Botanical Garden by Carlos Ferrater and Bet Figueras. Ferrater and Figueras’ proposal used computer modeling software to develop a triangular grid as a framework for planting and infrastructure in the garden: each triangular plane, retained by a series of COR-TEN steel walls, features a different Mediterranean plant community, with the slope and solar aspect of each plane mimicking ideal growing conditions in the plants’ native setting. (note 16) The triangular planes also provide a built-in system for evenly distributing an irrigation network through the garden, which is deployed across the same triangular grid as the planting beds. Even the visitor’s experience is guided by the faceting system, as paths follow the triangular network across its slope. In this sense, faceting transcends mere formal aspects and becomes inextricably embedded into both the function and experience of the garden.

Gwanggyo City Center: rendering by MVRDV. Image from here.

Mimesis

The ecological rigor that gives landscape urbanism its credibility also gives rise to an easy error: mimesis. All too often, the emphasis which landscape architects place on analyzing regional conditions and determinants, drawn from procedures tried and perfected in ecological planning as promoted by McHarg, Geddes, and others, (notes 17 and 18) results in a fascination with, if not fetishization of, mathematical and tectonic morphologies in nature. In this sense, technology acts as an enabler: the accuracy and ease of simulation and modeling software—for computing flows of surface and groundwater, tracking solar angles and predominant winds, modeling terrain, etc.—result in precise, complex mappings of environmental, biological, geological, or social phenomena. The novelty and aesthetic appeal of these mappings make them formally generative in a way heretofore rarely seen: too often this yields awkward scalar translations between regional and local scales or macroscopic and microscopic systems, prompted by desires to embed metaphor and context into design. Far from being confined to novice projects, these effects are common in competition entries and built work by established landscape architects and architects. Mimesis as a procedural artifact can be subtle or overt. For example, the MVRDV’s China Hills Exhibition and Gwanggyo Power Center and Vicente Guallart’s Denia Mountain and Wroclaw Expo (note 19) are speculative, unbuilt proposals that reduce highly specific geological operations—subduction, delamination, sedimentation, erosion—to superficial envelopes containing regularly spaced floorplates that belie the geomorphologies that inspired them. (note 20)

Governor’s Island as mollusk: rendering by James Corner Field Operations. Top image from here. Lower image from author’s collection.

To be fair, biomimicry often produces elegant proposals that enhance the performance of landscapes by using natural processes as the vehicles through which a site’s challenges can be addressed. For example, James Corner Field Operations and Wilkinson Eyre’s proposal for New York’s Governor’s Island, entitled Mollusk, reimagines the filter-feeding anatomy of mollusks as a series of earthworks. These earthworks act as cleansing biotopes for the tidal water in New York Harbor, as well as flood mitigators for the developed portion of the island. In this project, 3D modeling software allowed for precise testing and refining of the mollusk-inspired landforms under a variety of tidal and flood scenarios.

Keio University. Image from here.

Recursive Patterning

One of the more obvious examples of a computer-aided process revealing itself in built form is the explosion of algorithmic and parametric patterning in architecture and more recently landscape architecture. By harnessing lightning-quick computational processes, such as recursion, iteration, and conditional application of rules (parameters), it is now possible to quickly create highly complex field conditions that respond to structural, environmental, or aesthetic conditions. The fine grain of these patterns would have been exponentially more difficult, if not impossible, to achieve manually, and as such was rarely seen until recent decades—notable exceptions being Islamic architecture and the work of Antonio Gaudí. As in the work of the Moors and Gaudí, much of today’s algorithmic and parametric work in architecture rests firmly in the realm of ornamentation and the subdivision and rationalization of complex structures. While digital fabrication technologies such as water jet cutting, 3D printing, and CNC milling (note 21) have made it possible to build nearly any parametric façade or structure, they also make it all too easy to impose unnatural or excessive geometry that fails to respond to site conditions.

Keio University. Image from here.

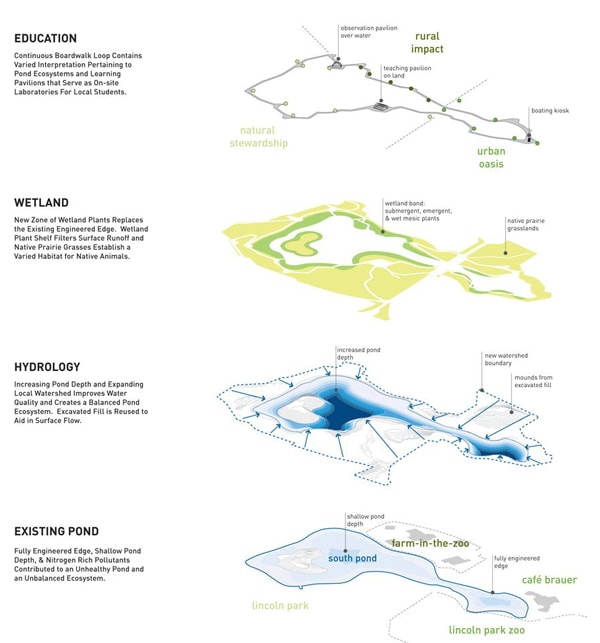

So, how can these patterns transcend ornamentation and become performative? In landscape, attempts at performative parametrics have often focused on gradients composed of discrete units that adjust in response to changing conditions. At their simplest, these gradients change incrementally as their topographical namesake implies: in response to slope. For example, to respond to hydrology, slopes have been articulated as impermeable fields punctuated by apertures that become incrementally larger where water collects, or as variably-sized paving units in a permeable field. An example of the aperture in the impermeable field is Michel Desvigne’s Keio University Roof Garden in Tokyo. In this project, rather than responding to slope, concrete tiles are perforated in a gradient pattern in order to allow patches of vegetation to poke through. Not only does this allow for the same unit paving system to be used for walkable surfaces and planting beds, it also helps to delineate and enclose paths.

Busan Cinema Complex: rendering by James Corner Field Operations. Image from here.

An example of paving units in a permeable field is the Busan Cinema Complex competition entry by James Corner Field Operations and TEN Arquitectos. In this project, topography stretches over subterranean water retention bladders. To subtly reveal the position of the bladders, the ground is articulated with a field of pavers that decrease in size where the bladders deform the surface.

Busan Cinema Complex: rendering by James Corner Field Operations. Image from here.

Design of paving units for Busan Cinema Complex developed by James Corner Field Operations.

While these two projects were certainly dependent on parametric modeling and computational simulation software—Keio University, for the creation of paving units, and Busan, for the topographical modeling and allocation of a slope-dependent field of pavers—hydrological gradients as a means of marking the groundplane are not new.

Land imprinting. Image from here.

One of the more innovative precursors is the Dixon land imprinting machine that, like the mill marks left by a CNC milling machine, employs a toothed roller attached to a bulldozer to emboss a pattern of V-shaped troughs and seeds into compacted soil. (note 22) This mechanical technology, if paired with the conditional adaptation enabled by parametric software, has enormous potential. By feeding sensor data into the machine, it could vary the depth and scale of the roller teeth and the speed of the bulldozer in real time, allowing it to respond to slope, the compaction or chemical makeup of soils, moisture content, and more.

Land imprinting. Image from here.

It is not difficult to imagine modifications to the Dixon machine that could be used to plant phytoremediative vegetation in response to contamination, break up asphalt in military sites or repurposed infrastructure, or introduce hydrophilic vegetation in areas that collect more water. By seeking economies of scale, whether through mass-produced paving units or sensor-fed equipment, parametric patterns can allow landscapes to easily respond to on-site conditions with a high-degree of specificity and little additional time and cost.

Yokohama Port Terminal. Photo ©Andrea Hansen 2009.

Topology

Ever since Rem Koolhaas and Bernard Tschumi gained worldwide acclaim for their schemes for the Parc de la Villette design competition in 1982, the line between architecture and landscape has come in and out of focus. This is due at least in part to an interest among many designers in blurring the lines between ground and enclosure. Architects are no longer satisfied designing walls and roofs, and landscape architects are not content to simply add greenery around the buildings. Rather, hybrid conditions have emerged in which ground becomes roof, walls fold into floors, and greenery creeps onto vertical walls and vegetated roofs. Topology—the mathematics of continuous, seamless surfaces—has been explored by artists such as Max Bill and M.C. Escher throughout the 20th century. Only through 3D modeling, however, have non-Euclidian and topological surfaces gained widespread use in the design of habitable spaces. The development of NURBS (non-uniform rational basis splines) curves and surfaces, which are manipulated by a cage of finite control points, allow complex continuous surfaces to be easily modeled even by novice users. Meanwhile, built-in operations for flattening or “unrolling” geometry and calculating ribs and cross-sections allow these surfaces to be panelized and codified so that they can actually be built.

Yokohama Port Terminal. Photo ©Andrea Hansen 2009.

One of the earlier examples of a topological landscape is the Yokohama Port Terminal by Foreign Office Architects (FOA), begun in 1995. This project utilized 3D modeling software (Microstation) to construct a continuous surface whose undulations allow it to act interchangeably as ground, roof, wall, and ceiling. In the built project, continuous curvature is achieved by using a system of wooden planks that are present on both the interior and exterior surfaces.

Southeast Coastal Plaza. Photo ©Andrea Hansen 2009.

The theme of topological curvature reappears in a later project by FOA, the Southeast Coastal Plaza in Barcelona (2000-2004). (note 23) In this project, a single unit (a crescent shaped paver) is deployed across the site, changing from pathway to amphitheater, skate ramp, and retaining wall. Though some design details have been overlooked—apertures for drains and tree planters, for instance—the project succeeds in creating a continuous surface that is enclosed yet almost entirely accessible. As modeling software improves and rapid prototyping of 3D models becomes faster and cheaper, the boundaries between architecture (enclosure) and landscape (ground) will become increasingly porous. It is important, however, that the built outcomes of 3D surface modeling become more than manifestations of forms floating in a model space unencumbered by real-world scale, context, and materiality. By registering localized ecologies such as solar angles, panoramas or barriers, or active and passive zones, topological decisions can become intelligent drivers of the way people experience landscape.

Southeast Coastal Plaza. Photo ©Andrea Hansen 2009.

Conclusion: Digital Media and Performance

The act of classifying procedural artifacts is not a question of authorship: the four categories outlined above speak less to the presence of the designer’s hand, skill, or intuition, and more to a transparent use of digital technology. (note 24) True, the designer plays a vital role in even the most computationally advanced schemes: she devises the generative logic, sets and resets the parameters, chooses the permutations, and creates the drawings. Nonetheless, remnants of the computational toolkit have a persistent, unmistakable syntax that evokes the back-end mathematics of design software: the meshes and surface analogs, the computational algorithms, the back-and-forth, do-and-undo recursion involved in translating concept to code. The real question of agency is raised by the intentionality of these digital relics. Is it necessary or even effective to leave traces of the technology we use on the landscape? Does the rapid turnover of what is “cutting edge” in computational design and the gap between conception and construction—over many months, if not years—leave landscape architects susceptible to seeming passé even before a project’s newly-planted trees have time to set roots? Or is the act of embedding contemporary thought, design, and fabrication processes into the built landscape as critical to the historical documentation of this epoch as it was when Mies ushered in the structural honesty of modernism with his adoption of the mantra, “less is more?”

Perhaps the answer lies less in the whims and wherefores of designers and their critical allies, and more with the people who experience landscapes on a daily basis with little awareness of, or care for, spatial logic, let alone the toolmarks that the design process leaves on a site. An excellent example of the way that trained and untrained eyes have wildly differing perceptions can be found in the comparative sketches of roadside landscapes in The View From the Road by Donald Appleyard and Kevin Lynch. (note 25) Ultimately, qualitative successes are what make landscapes great at any scale: the social relationships they engender, the ecological and environmental benefits they impart, the ephemeral delights—whether the sheer pleasure of walking in dappled sunlight under a leafy canopy, or the relief of dipping one’s feet in cool water on a hot summer’s day. The successful examples cited in this essay embrace the artifacts of digital media not for their formal qualities, but because, in some way, the chosen forms support the performance of the landscape. Technology helps to make sense of our complex world, and at its best it helps translate environmental and social processes into designs that bring people together, improve underperforming sites, and promote healthy cities. Moreover, as a core aspiration, technology enables landscape architects to focus on what they do best: creating vibrant, dynamic, and robust landscapes that enable plant, animal, and human inhabitants to thrive.

For more examples of the varied ways in which digital media is revolutionizing landscape architecture, check out the projects in the Digital Terrain series in strategies: Aidan Acker’s Sited: Digital Strategies, Allison Dailey’s Underworld, and Max Hooper Schneider’s Monist Kingdoms. See also A. Scottie McDaniel’s catalog of representational instruments, Patterns of Representation, for further breakdown of contemporary representational techniques and how they are employed in the conceptual realm.

Andrea Hansen is Daniel Urban Kiley Fellow and Lecturer in Landscape Architecture at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design, where she teaches core and option studios and lectures on representation and advanced digital media. Her research and design practice, Fluxscape, focuses on the development of responsive landscape infrastructural frameworks that express urban and ecological contexts through ephemera and gradients. Andrea holds a Master of Landscape Architecture and a Master of Architecture from the University of Pennsylvania, where she was the recipient of several awards including the George Madden Boughton Prize, the Warren P. Laird Award, the William M. Mehlhorn Scholarship, and the Van Alen Traveling Fellowship. She also holds a Bachelor of Arts in Urban Studies and Civil Engineering from Stanford University.

Andrea Hansen is Daniel Urban Kiley Fellow and Lecturer in Landscape Architecture at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design, where she teaches core and option studios and lectures on representation and advanced digital media. Her research and design practice, Fluxscape, focuses on the development of responsive landscape infrastructural frameworks that express urban and ecological contexts through ephemera and gradients. Andrea holds a Master of Landscape Architecture and a Master of Architecture from the University of Pennsylvania, where she was the recipient of several awards including the George Madden Boughton Prize, the Warren P. Laird Award, the William M. Mehlhorn Scholarship, and the Van Alen Traveling Fellowship. She also holds a Bachelor of Arts in Urban Studies and Civil Engineering from Stanford University.

Note 1: See Meg Studer’s interview of Charles Waldheim in this issue of landscape urbanism (dot) com for further discussion of landscape urbanism’s roots in ecological planning.

Note 2: Mieke Bal and Norman Bryson, “Semiotics and Art History,” in Art Bulletin 73, no. 2 (Jun., 1991): 174-208.

Note 3: Robert Venturi, Steven Izenour and Denise Scott Brown, Learning from Las Vegas: The Forgotten Symbolism of Architectural Form (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1977).

Note 4: “Jacob Javits Plaza, New York, New York,” Martha Schwartz Partners, accessed November 12, 2011. http://www.marthaschwartz.com/projects/javits_details.html

Note 5: Laurie Olin, “Drawings at Work,” in Representing Landscape Architecture, ed. Marc Treib. (New York: Taylor and Francis, 2008). “Drawing is an act of thinking. If you can’t draw something, you probably can’t make it.” 155.

Note 6: Ibid. “While equal in age to drawings for building, landscape documents have experienced greater difficulty in achieving accurate representations. . . . One traditional method first creates a recognizable view and then alters it by redrawing or overlay, annotating the new view with comments on the work intended.” 144.

Note 7: Dianne Harris and David Hays, “On the Use and Misuse of Historic Landscape Views” in Representing Landscape Architecture, ed. Marc Treib. (New York: Taylor and Francis, 2008) 22-41.

Note 8: Stephen Daniels, Humphry Repton: Landscape Gardening and the Geography of Georgian England (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1999).

Note 9: Kirt Rieder, “Modeling, Physical and Virtual,” in Representing Landscape Architecture, ed. Marc Treib. (New York: Taylor and Francis, 2008).

Note 10: Marian Bozdoc, “The History of CAD,” accessed October 17, 2011. http://www.mbdesign.net/mbinfo/CAD-History.htm

Note 11: As with splines, today’s CAD systems find the basis for many tools—fillets, chamfers, lines, and arcs—in hand-drafting techniques, just as Photoshop’s core digital tools reference analog techniques (paintbrush, pencil, and eraser from drawing, dodge and burn, from photographic printmaking).

Note 12: Grasshopper for Rhinoceros 3D and Bentley’s Generative Concepts, for example.

Note 13: William J. Mitchell, “Foreword” to Kostas Terzidis, Expressive Form: A Conceptual Approach to Computational Design. (London, UK: Spon Press/Routledge, 2003).

Note 14: Robin Evans, “Translations from Drawing to Building,” Translations from Drawing and Building and Other Essays. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1997). “Not all things architectural . . . can be arrived at through drawing.” 159.

Note 15: James Corner, “Representation and Landscape: Drawing and Making in the Landscape Medium,” Word & Image 8, no. 3 (July-Sept 1992) 243-275.

Note 16: Carlos Ferrater, Synchronizing Geometry. (Barcelona, Spain: Actar, 2008).

Note 17: See also Meg Studer’s interview of Charles Waldheim in this issue of landscape urbanism (dot) com for further discussion of landscape urbanism’s roots in ecological planning.

Note 18: See also Shanti Fjord Levy’s “Ground Landscape Urbanism” in Issue 1 of this journal.

Note 19: Vicente Guallart, Geo-Logics: Geography, Information, Architecture. (Barcelona, Spain: Actar, 2008).

Note 20: It is perhaps indicative of the sometimes conflicting priorities of landscape architects and architects that all of these projects were architect-designed.

Note 21: For an excellent and highly-readable overview of digital modeling fabrication technologies, see Branko Kolarevic, “Digital Morphogenesis” and “Digital Fabrication” in Architecture in the Digital Age: Design and Manufacturing. (London, UK: Spon Press, 2003).

Note 22: For more information, see http://imprinting.org/.

Note 23: Foreign Office Architects, Phylogenesis: FOA’s Ark. (Barcelona, Spain: Actar, 2004).

Note 24: For a discussion of the traces of authorship in the process of making, see the critique of James Turrell in Robin Evans, “Translations from Drawing to Building,” in Translations from Drawing and Building and Other Essays. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1997).

Note 25: See also issues of disjuncture as presented in experienced vs. drawn translation of Rittenhouse Square in Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities. (New York: Random House, 1961).

Sarah Kathleen Peck is a writer, designer, and storyteller. In 2011, she created the LandscapeUrbanism.com website and served as the co-editor of landscape urbanism journal issues 01 and 02 and the editor of the website. Her work lies in the spaces between environments, technology, communications, and strategy. She grew up in Palo Alto, and graduated with a BA in Psychology from Denison University and an MLA from Penn Design. She currently writes and teaches storytelling workshops across the country.

Sarah Kathleen Peck is a writer, designer, and storyteller. In 2011, she created the LandscapeUrbanism.com website and served as the co-editor of landscape urbanism journal issues 01 and 02 and the editor of the website. Her work lies in the spaces between environments, technology, communications, and strategy. She grew up in Palo Alto, and graduated with a BA in Psychology from Denison University and an MLA from Penn Design. She currently writes and teaches storytelling workshops across the country.

Gerdo Aquino is the President of

Gerdo Aquino is the President of