The landscape of a country is always a playground for political events. So it is in the case of Russia, where over the past century, across a huge territory, almost all the landscape of the country has undergone significant changes as a consequence of evolving political and strategic interests.

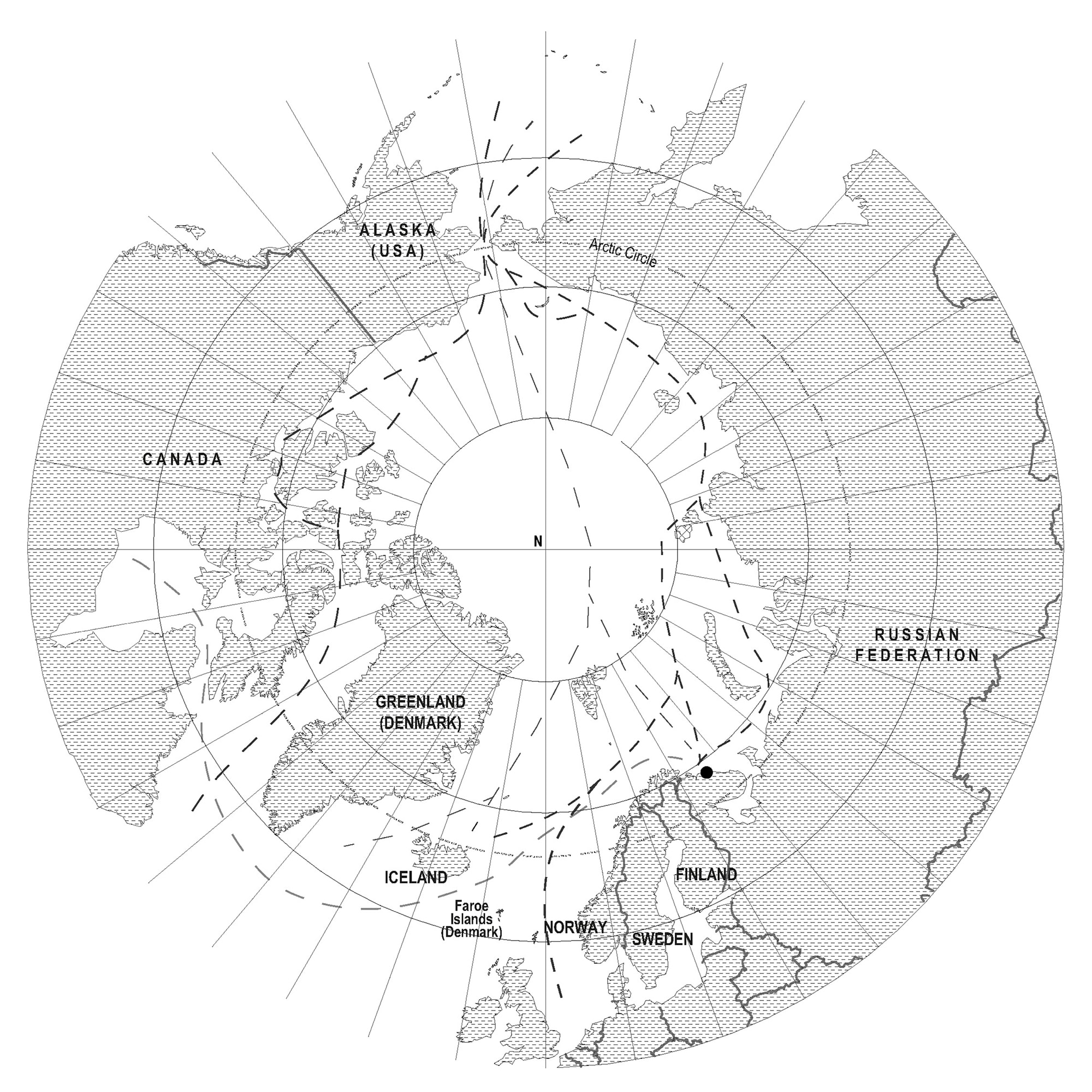

Teriberka on the world map

Though the Northern Territories are defined by extreme conditions, they were articulated as being of extreme importance based on their abundance of resources. At the beginning of the 20th century, they became the sites of heavy industrialization processes, based on the planned economy. In order to rapidly explore and industrialize the land, the whole territory was redefined as a huge machine, which has to work coherently to achieve these goals [1]. The North had to become the main provider for this program. Therefore the Northern pioneer cities were established to maintain the enormous masses of workers, resettled from all over the country.

From a geopolitical perspective, fighting for the North nowadays makes more sense than ever before. Nevertheless, the question of fighting for human presence in the North remains open. Certainly, keeping a constant settlement in the North is unprofitable, demanding lots of resources and energy while constantly facing new problems [2].

Security

The notion of the “border zone” defines the special status of the perimeter lands of the Russian state, with precise restrictions on access and land use [3]. Historically the settlement structure in the border areas was based on economic and cultural exchange with the bordering countries (traditionally this territory was under the responsibility of the Ministry of Finance). The coastline settlements were naturally established during the process of land development from the seaside, and they were sea-oriented in terms of resources and of the means of transportation. In the 20th century, the border zone became a “frozen belt”, which caused the “thinning” of the territories along the borders (with the forced evacuation of residents to other settlements inland) [4] and the placing of new outposts (in fact military bases) along the coastline. Many cities became isolated military-industrial “closed cities,” with access tightly regulated.

With the collapse of the USSR the border regulations were temporarily suspended and the width of the border zones shrank to 15 km. Moreover, their oversight was given to the regional administrations, which resulted in the monopolization of resources (especially where fossil fuels and natural sea resources are concerned).

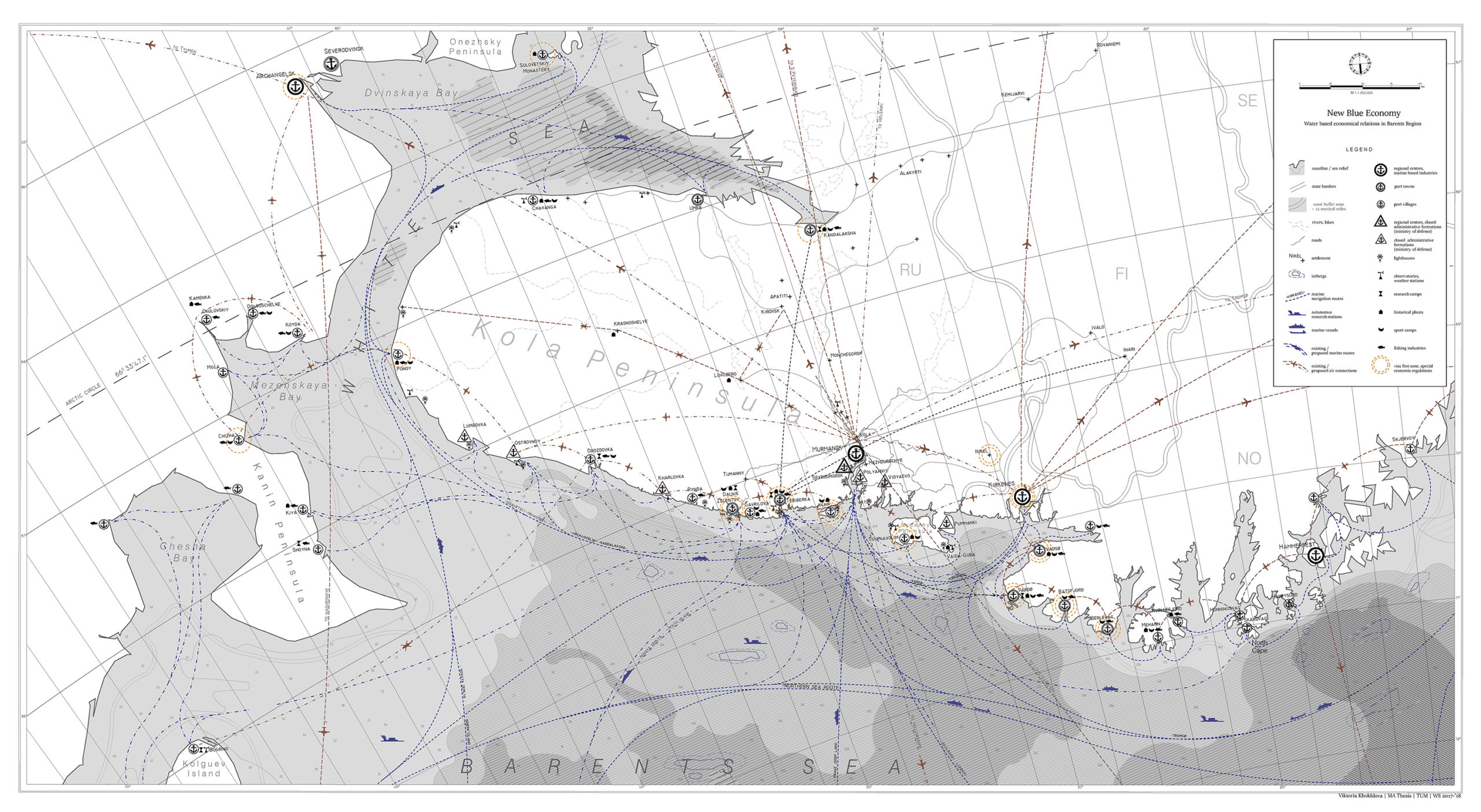

“New Blue Economy”: Water-based economic relations in Barents Region

Vicinity of Teriberka

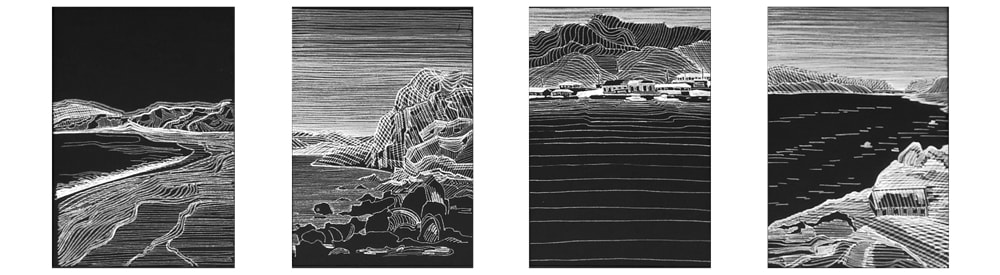

Forever Ephemeral

After the end of resource-intensive investment in arctic settlement during the 20th century, the North nowadays is balancing between the thinning epidemic of population loss and the new models of extraction-driven Petropolis utopia. In the contemporary conditions driven by the market economy and the age of advanced technology, the land is rated mainly by its profit value, with no regard for the essence of the local landscape. Present trends illustrate increased human dependence on natural resources and maintenance of the ecological balance, though it has already become an unattainable goal.

The historical nomadic nature of settlement is back, but in a new form, driven by hydrocarbon resources and operated by machines. The tendency of relocations from uninhabitable northern sites runs parallel to official abandonment of the settlements, partially maintaining just a few strategic ones. The consequences of such trends are already visible, but the real effects will present themselves in the nearest future. The new explorations are realized in a nomadic way with constant relocations and temporary structures. This, on the one hand, thins the land and the urban structure, and on the other creates new transformations which lead to the vitally important re-urbanization of the land, gradually erasing the traces of the previous interventions. But whereas the fossil fuel-based nomadic urbanism with its exploitative nature destroys the natural land- and waterscapes, with no possibility for recovery, there are other rational and responsible ways to develop these territories.

Research Camp Teriberka

Impossibility of the North

The small remote fishing village of Teriberka used to be known as one of the rest stops on Pomor [6] trade routes between Norway and Russia from the 16th century. Then it was constantly varying in scale seasonally (from 10 residents in the wintertime to up to 800 visitors).

Teriberka was established as a sea-based settlement, oriented on the use of sea resources and oriented at international trade and connections. Nowadays the settlement has become introverted and shifted its orientation towards the land, deprived of its main defining source — the waterscape. It is remote and lacks basic infrastructure and ground transportation facilities.

Just recently (2009) the “closed city” status — now known in post-USSR modern Russia as a “closed administrative-territorial formation” — was repealed in Teriberka and some other settlements at the Kola Peninsula during the preparations for the new gas-development project at the Stockman field in the Barents Sea [7]. The land which used to be isolated from the public for many years became accessible to everyone, including international tourists. Nevertheless, the area extending from the coastline out to 12 nautical miles offshore remains in the status of the territorial waters (1982, United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea). This status presupposes the existence of certain special regulations on use. This means, that the coastline location affects the economic, cultural and everyday life of the settlement.

Barents Region Network

Barents Region

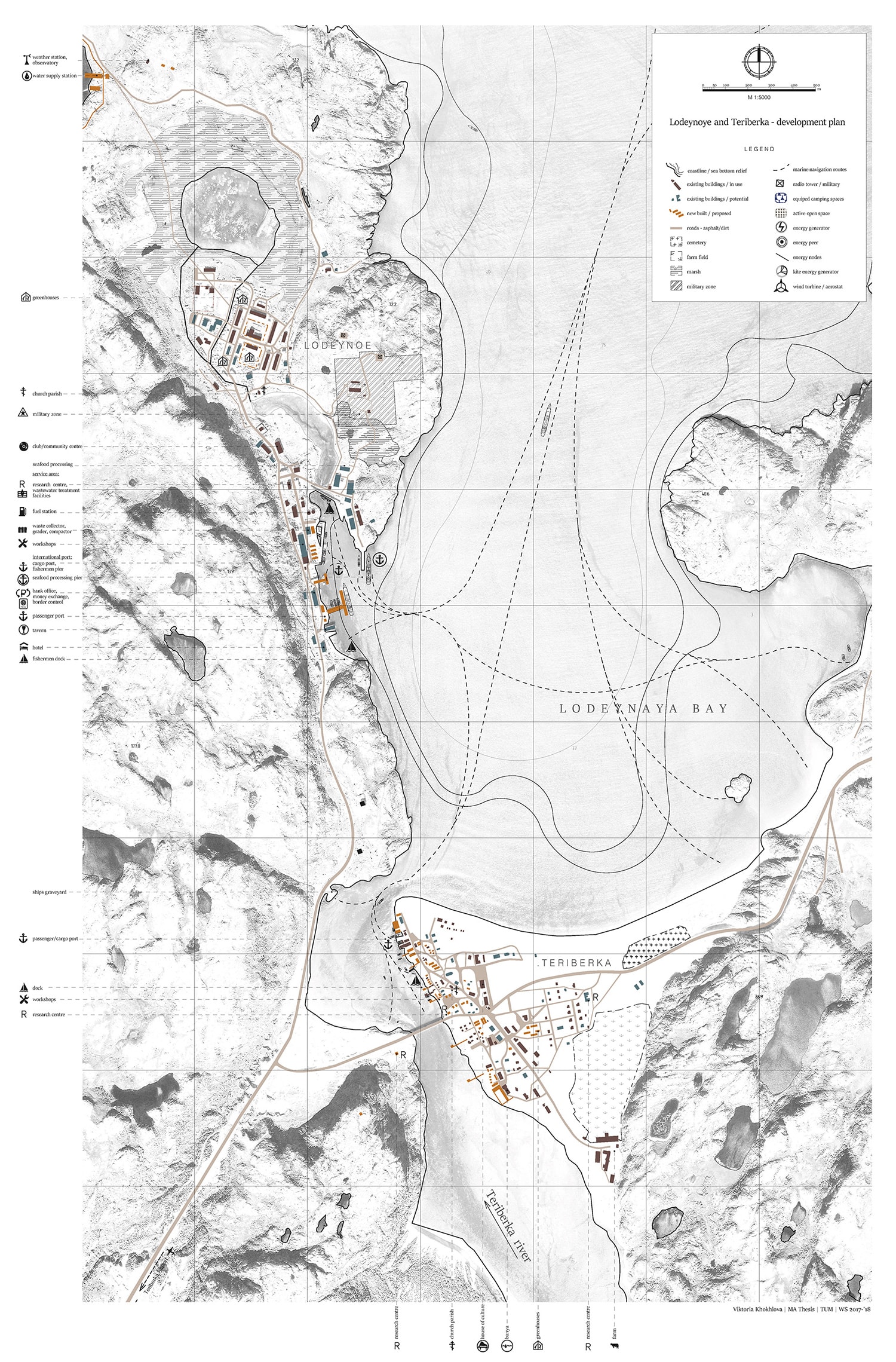

Considering territory not as part of a national state but rather as the coexisting place of certain communities, which share common interests and have to deal with similar issues, sparks reconsideration of the notion of national borders and the introduction of borderland regulations. Land with open borders is more likely to be populated by open-minded people. In this project, the Barents region evolves into a self-sustaining territory, founded on special economic regulations.

New Blue Economy shall be established in the network of settlements along the coastline of the Barents Sea and the White Sea. Providing the rural areas of Finnmark and Kola Peninsula with strong water and air connections aims to deal with the remoteness and support the economy, as well as establish new cultural interactions. Amongst other improvements is to make the territory of Teriberka and some other northern cities a visa-free zone as a part of special economic agreements and cooperation. This dispersed but networked structure of compact units promises to become a strong alternative to urban sprawl.

Shrinking settlements are becoming highly unprofitable and hard to maintain in the traditional way, especially the remote ones. When the settlement gets too small, it is in need of re-organization and re-establishing of basic life principles. This project proposes to turn coastal settlements into autonomously functioning units, taking advantage of the weather and natural environment and benefiting from it wherever possible. Sufficiency is the key aspect of the new lifestyle. By providing communities with basic necessities, each settlement finds its own balance of communal and individual demands.

Settlements can be considered as islands, nodes of a decentralized network. Self-sustaining to the maximum extent possible, they strive not only to survive in severe Arctic conditions but also to accumulate the strength of the communities. In order to keep and develop their links to other settlements inland and internationally, localities (each one acting as an independent member) use such instruments as cultural festivals, sports competitions, discussions, open forums, and celebrations, involving their neighbors from the Region to participate. Teriberka, as part of this network, shall become simultaneously both globally open and site-oriented.

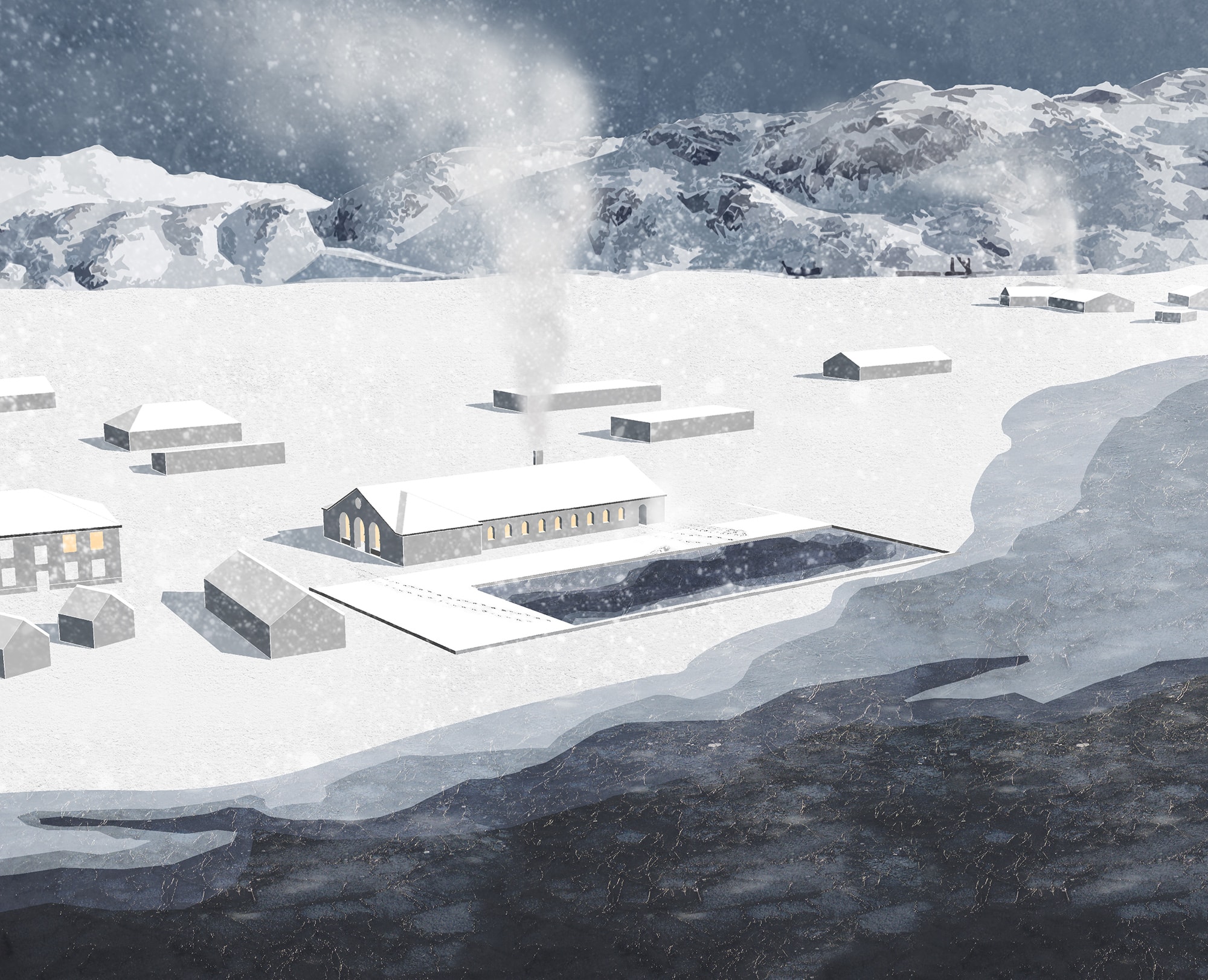

Teriberka: View from above. Para-kites are harvesting wind energy

Research Camp Teriberka

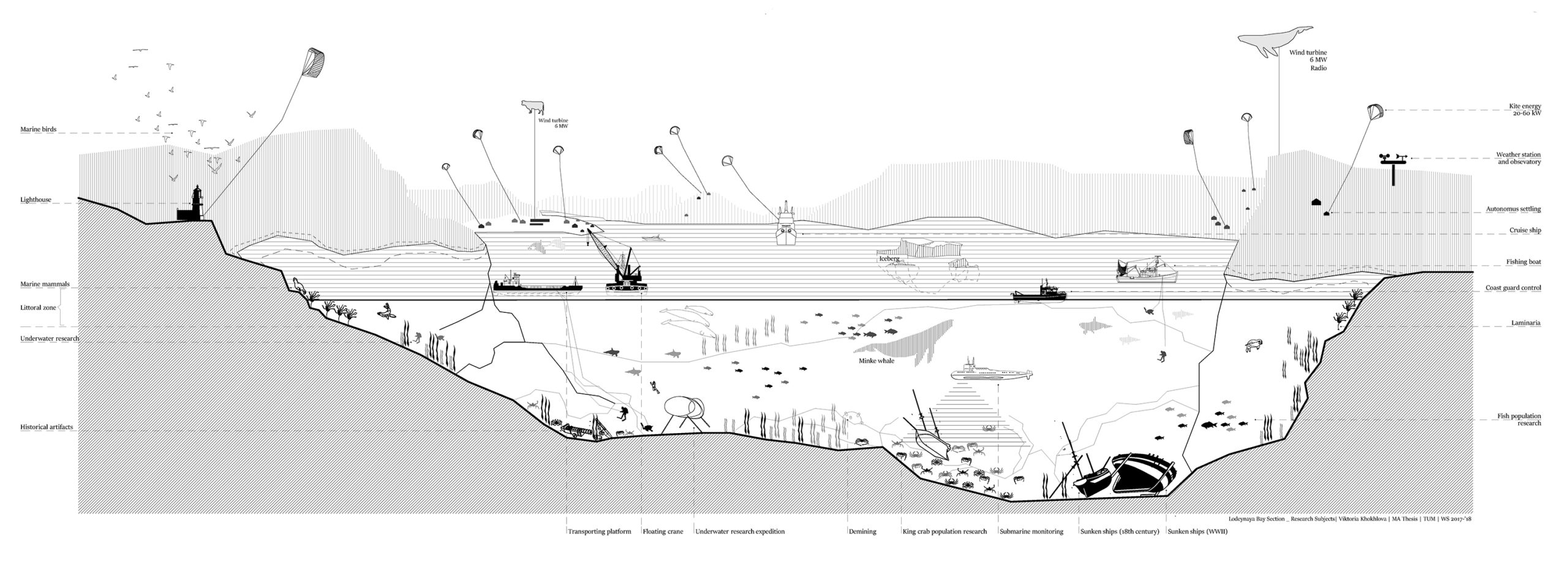

Aiming to meet a healthy balance between the natural environment and the artificial elements as a continuation of the landscape, the area around the settlement turns into a research camp. To be able to act sufficiently and responsively, the specialists would have to diagnose the landscape and the waterscape simultaneously.

The project also involves embedding of new technology, testing it specifically in a northern environment. Companies are welcome to test their pilot projects and to contribute to the stable development of the village. In order to maximally profit from the geographical location and overcome the negative factors of the remoteness, the implied projects are to profit on modifying the basic service facilities into responding efficiently and creatively to the climate, as well as to integration in the public.

Lodeynaya Bay Section: research subjects

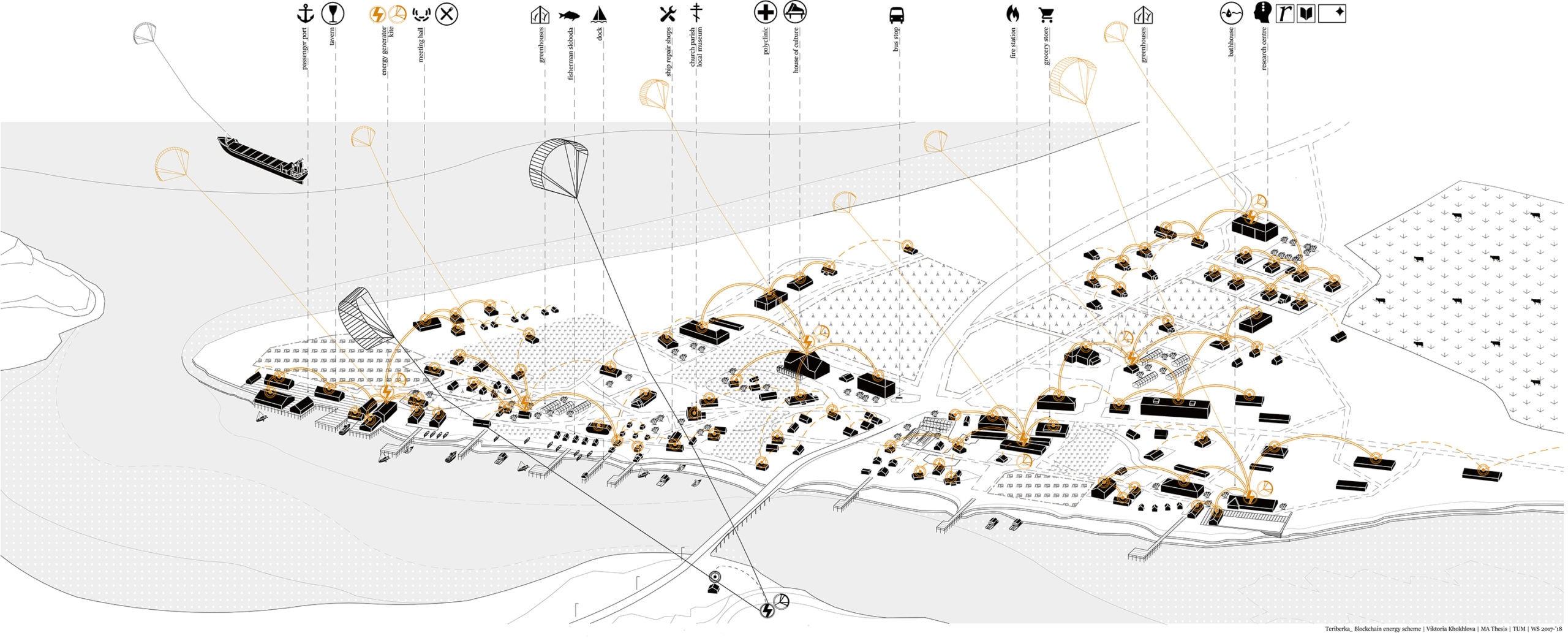

Axonometric view of the Teriberka village showing the blockchain energy scheme

There is considerable potential for the Kola Peninsula coast to provide itself autonomously with renewable wind energy [8]. Once deployed, a para-kites system would serve the dynamic and publicly accessible process of harvesting wind energy in the entire Arctic region, and in Teriberka in particular [9]. Unlike contemporary large-scale wind infrastructures, this system would respond to the dynamic character of the tundra landscape – it could become an iconic marker of the dispersed nomadic settlements. Decentralized autonomous networks, based on the blockchain peer-to-peer principle, shall manage the resource consumption in the villages. Thus it shall enable people to explore potential effects of decentralized energy, currency, and governance on their lives while being not anchored to one place.

Interactive and responsive programs shall involve both residents and visitors in order for them to contribute to the research programs of testing the viability of locally produced, renewable wind energy for domestic services (such as electrical, heating, water and sanitation supply systems, transport connections), as well as for sport and leisure activities. The results of such experiments, as well as the process of testing itself, will be available at the open data centers situated in both Teriberka and Lodeynoe, and will be discussed and negotiated with the locals publicly. Thus the whole process tends to be maximally transparent and will be sure to generate public awareness, discussion, and the efficient communication of Teriberka’s future plans.

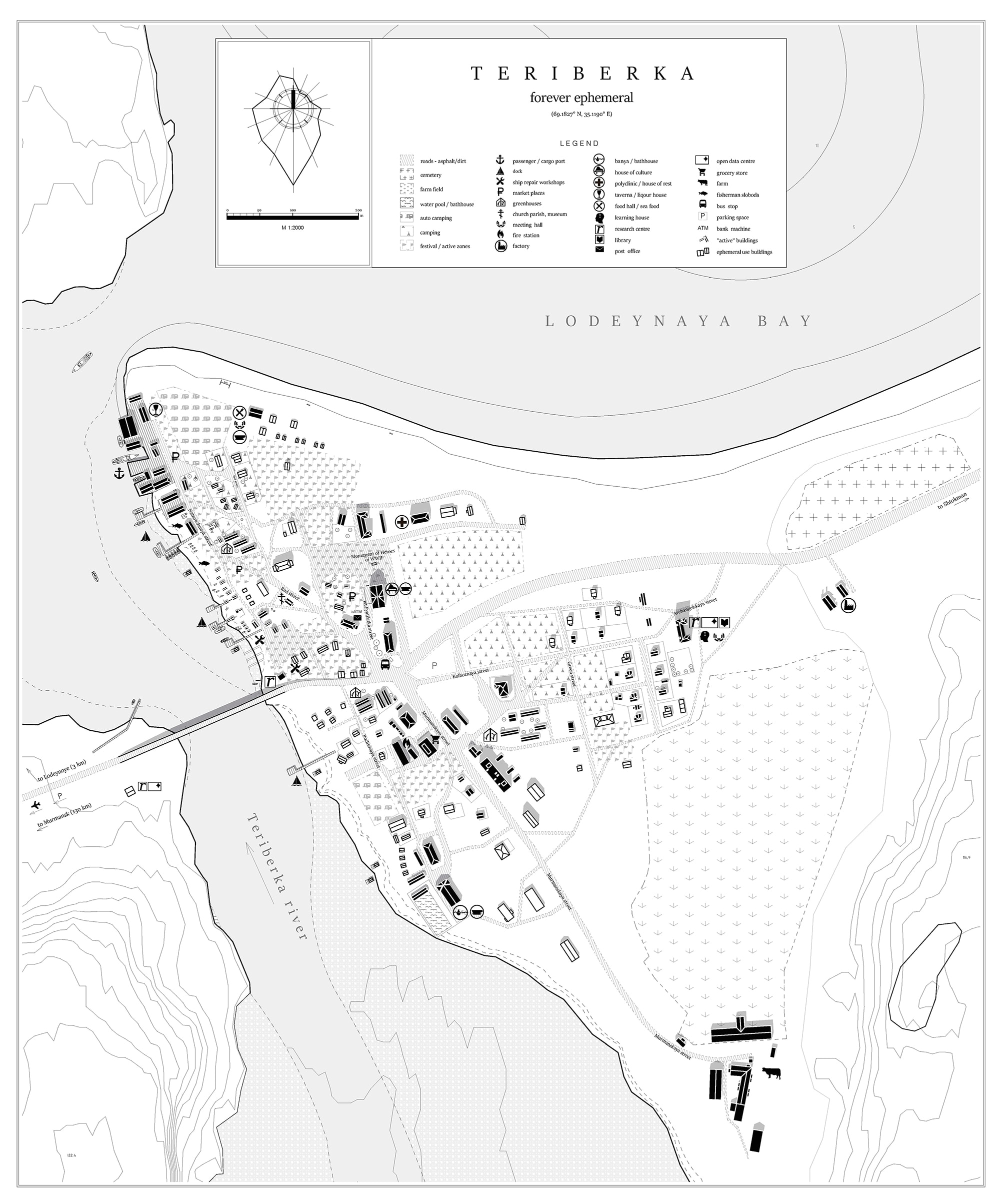

Teriberka: forever ephemeral

Nomadic Nature

In the land of eternal light and eternal night, where the oceans control the weather and the natural cycles, provide the food and energy, the lifestyle is totally based on Nature. Its already vibrant character is overlapped with the range of human activities, celebrations, festivals, and other forms of collectivity. Untouched territory here serves as a unique opportunity to rethink human presence in a delicate ecological context, and to benefit from the continuous void.

The physical structures are not of importance for the nomadic camp. Space may be transformed intellectually, programmatically, technically, atmospherically, mythically — the physical is not a constant. Temporal life-supporting structures play the biggest role in such settlements. For Teriberka and Lodeynoye, as for the water-based localities in the remote North, the critical facilities are transportation, energy and heating systems, water and food supply.

Lodeynoye and Teriberka – development plan

Year events calendar – occupation of the space

In the project, space becomes expressed by the routine rituals and traditions — in other words, the necessary domestic everyday activities, which are tied to the lifestyle of the Russian North so inseparably, that they shape the architectural environment. The facilities are intended to fulfill the fisherman’s daily routines, the possibility of weekend escape (dachas). They include a public banya and water culture center (as traditionally there are no baths in most of the houses), private family banyas, farming (with greenhouses to fully benefit from the solar activity in summertime), a tavern (in the Russian tradition one should never drink alone), tea rooms, organized outside places for communication or contemplation, and a health resort and rehabilitation center on the sandy coast. Apart from these facilities, there shall be some intended to recover the decayed but still desirable community public establishments, as well as those supporting the existing forms of collective life, such as the church parish, school, and kindergarten, house of culture, community club (allowing for all the different activities from the disco and theatre to the weekly sports and round-tables).

All these centers of activities and local life in the villages are aimed at providing the residents and visitors with the clearly traditional and necessary forms of interactions and engagement with the landscape. Even if it does not show demand, even if the populations remain small, Teriberka needs principles and structures capable of varying in scale or being altered whenever needed, both intellectually and physically, in both the landscape imagination and the architectural reality.

Banya in the village

Viktoria Khokhlova is an architect and urbanist who enjoys working with spaces and future scenarios. She studied in Russia, Lichtenstein and Germany, where she obtained her Master Degree in Architecture (M.A., Dipl.-Ing.) at the Technical University of Munich (TUM). Viktroia has worked alongside international colleagues on projects in Moscow, Tyumen, Eindhoven, and is currently based in Munich.

Notes

[1] Koolhaas, Rem. (2018). “Koolhaas on the Countryside.” Arquitectura viva (203), p.12. http://www.arquitecturaviva.com/en/Info/News/Details/12124. Originally published in The World in 2018 yearbook of “The Economist” and in “Tiempo.”

[2] Sheppard, Lola and Mason White. (2017). Many Norths: Spatial Practice in a Polar Territory. Actar Publishers.

[3] Official publications of Border Security Zones limits across the subjects of the Russian Federation, http://www.pravo.gov.ru/

[4] Martin, Terry. (1998). “The Origins of Soviet Ethnic Cleansing.” Journal of Modern History 70, no. 4: 813-861. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:3229636

[5] White, Mason and Lola Sheppard. (2008, August) “Thawing Urbanisms in the Arctic.” MONU, No. 09: Exotic Urbanism.

[6] “Pomors.” Barentsinfo. Retrieved from http://www.barentsinfo.org/Contents/Indigenous-people/Pomors

[7] Minin, Valery. (2012). “Economical aspects of the small-scale renewable energy development in the remote settlements on the Kola Peninsula.” Murmansk: Bellona Foundation. https://network.bellona.org/content/uploads/sites/3/fil_Economic_Aspects_of_Small-Scale_Renewable_Energy_Development_in_Remote_Settlements_of_the_Kola_Peninsula.pdf

[8] On the 26th of December2020 Shtockman Development AG had announced the liquidation of the company and its branch in Teriberka; www.shtokman.ru

[9] The Kite Power Systems technology has been researched and developed since 2011 by a team of engineers at KPS. “Technology.” KPS, Retrieved from http://www.kps.energy/

Cite

Viktoria Khokhlova, “Arctic Present: The Case of Teriberka,” Scenario Journal 07: Power, December 2019. https://scenariojournal.com/article/arctic-present/