Coal-fired power stations play a critical role in the production of electricity in the United States. Coal is delivered to the power plant, coal is burned to turn water into steam, turbines spin the generators, and electricity is created. Unfortunately, this is not the end of the story.

Since the dawn of coal-fired power stations, a stream of waste has been continuously growing. As coal is burned to produce electricity, non-combustible byproducts are collected from the stack and boiler, water is added, and the slurry is piped into pits in the landscape. In 2017, over 111 million tons of coal ash were produced in the U.S. [1].

Historically, coal ash has been stored in unlined intrusions in the landscape. Commonly referred to as coal ash ponds, these waste sites are contained by earthen dams. Without a liner, the liquefied coal ash can seep into groundwater. The earthen dams are continuously threatened by storms, flooding, and engineering failure. These ponds are an unstable form of containment.

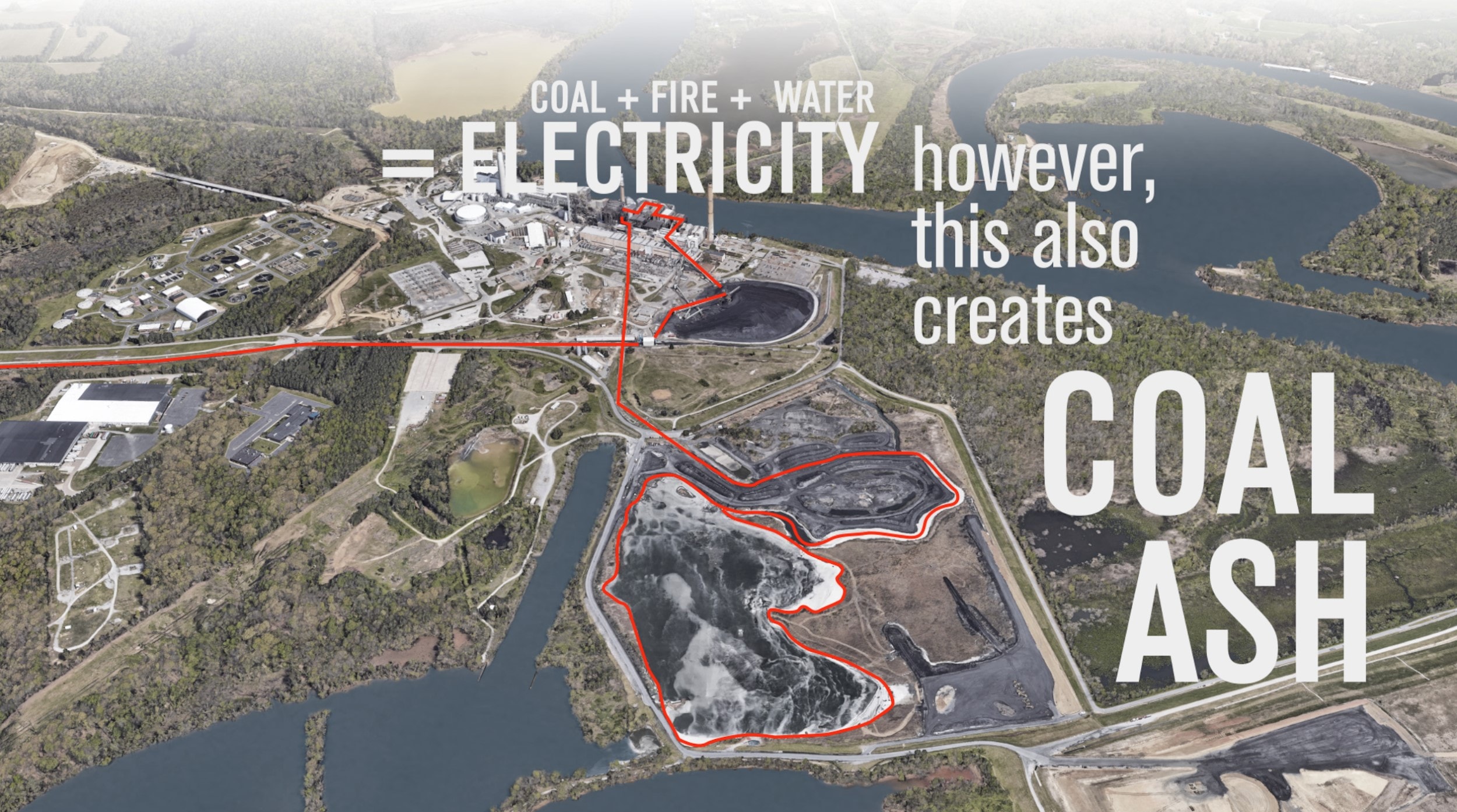

Chesterfield Power Station and coal ash ponds, Chesterfield, VA. Chesterfield Power Station is the largest fossil-fueled power station in Virginia [2]. Image by Lauren Delbridge

The Hidden Problem

As coal ash is left to rest in ponds, the problem comes from the heavy metals within the ash itself. As coal is burned, trace amounts of arsenic, lead, cadmium, mercury, and other metals remain in the ash. Coal-fired power plants are generally located along rivers and bodies of water, and so their coal ash ponds pose an even larger threat to water supplies. For decades, these coal ash ponds have gone relatively unnoticed by the public and the media, allowing the waste and dangerous contents to seep and spill into surrounding communities and waterways.

How did we get here?

The placement of these coal-fired power stations is most concerning. These power stations are dependent on two constants: water and space. This leads to an unfortunate pattern of placement on the cheapest land along the water’s edge. In many cases, the communities around these power stations were already at a disadvantage. A 2012 NAACP report revealed that individuals living within three miles of a coal power plant have an average per capita income of $18,400, which was less than the U.S. average of $21,587. In addition, an estimated 39% of these individuals are people of color [8]. Coal ash ponds have only added to the struggles of these vulnerable communities. The heavy metals in coal ash leach into the groundwater that many households rely on for their drinking water wells. The ash can seep into the nearby rivers and lakes used for recreation, and the dams used to contain the ash ponds can fail, resulting in large-scale disasters.

Flow of materials in coal-fired power stations. Image by Lauren Delbridge

We have, rightly, spent decades focusing on the carbon emissions of coal-fired power stations, but coal ash ponds pose an even more immediate safety threat. In 2008, a dam failure at Tennessee Valley Authority Kingston Fossil Plant resulted in over 1 billion gallons of coal ash flooding the Emory River [3]. In 2014, a ruptured pipe at a North Carolina Duke Energy retired power plant sent over 39,000 tons of coal ash into the Dan River [3]. These catastrophic events captured the attention of the EPA and led to long-awaited attempts to regulate coal ash ponds.

In December 2014, the EPA set the first national standards for coal ash disposal. In addition to forcing significant-hazard or high-hazard coal ash ponds into regulatory compliance, the rule also recognized coal ash itself as a “non-hazardous waste” [4]. This classification was meant both to encourage the beneficial reuse of ash, and to hand over control of these ponds to states. The non-hazardous label allows states, and not the EPA, to be the enforcers of coal ash legislation. Ultimately, coal ash ponds are being forced to close across the nation.

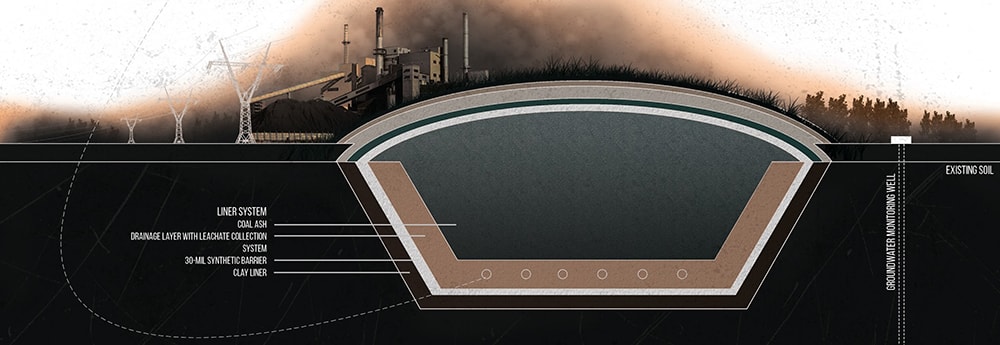

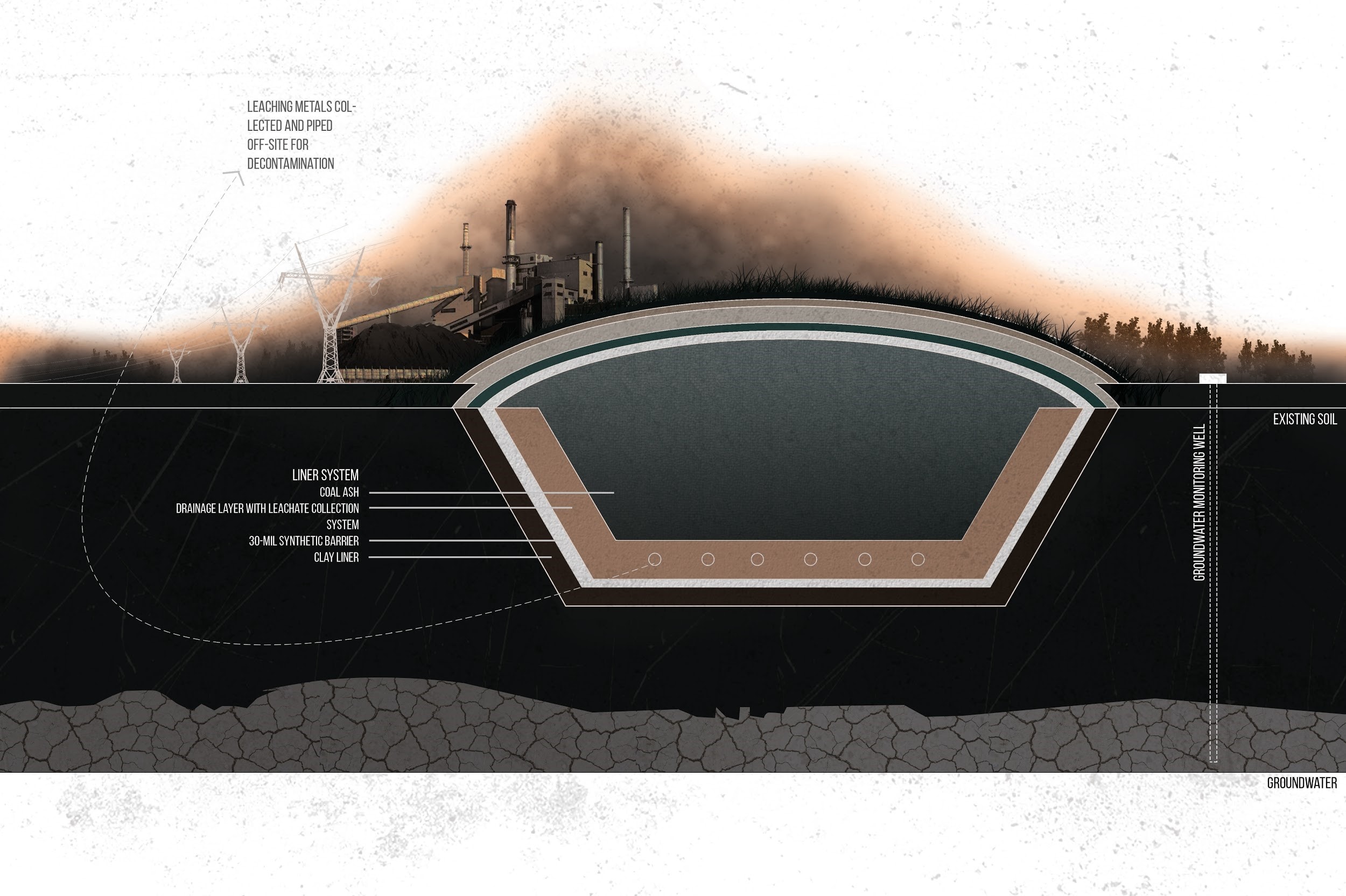

Coal ash ponds are at a critical point of flux. Currently there are two widely accepted closure methods for coal ash ponds. The cap-in-place solution dewaters the ash in place, caps the waste with an impermeable geomembrane layer, and leaves the waste sealed in place [5]. The clean closure solution dewaters the ash, excavates the waste, and relocates the material to an engineered landfill [5]. While both solutions are engineered to minimize seepage and spills, they aren’t creating spaces with people in mind. Coal ash ponds have been damaging communities, waterways, and the environment for many years; now is the time to reclaim these wastescapes.

Clean closure engineered solution. Fully lined landfills contain possible contaminants but make no space for people. Image by Lauren Delbridge.

A Nation Covered in Ash

Nearly every state in the U.S. is affected by a coal ash site. In Charlotte, North Carolina, there are three coal-fired power plants with coal ash ponds within 30 miles from my home. Even more troubling is the fact that two of these power plants and their respective ash ponds are on the banks of lakes that supply the city of Charlotte’s drinking water. Designated by the EPA as high hazard coal ash ponds, these ponds are a threat to the city’s water supply, a story shared by many towns and cities across the nation [6].

Coal ash waste sites in the United States. Image by Lauren Delbridge

How can we transform these wastescapes?

Now is the time to think innovatively about coal ash ponds and the potential future of these sites. As ponds across the US are being forced to close, we should be pushing beyond an engineered solution. There is a growing amount of research surrounding the reuse and recycling of coal ash; however, the majority of coal ash is still disposed of in a coal ash pond or landfill.

Landscape architects should be driving the conversations about what these sites can become. It is imperative to reclaim these damaged lands, and to do so in a way that responds to communities, water systems, and the environment.

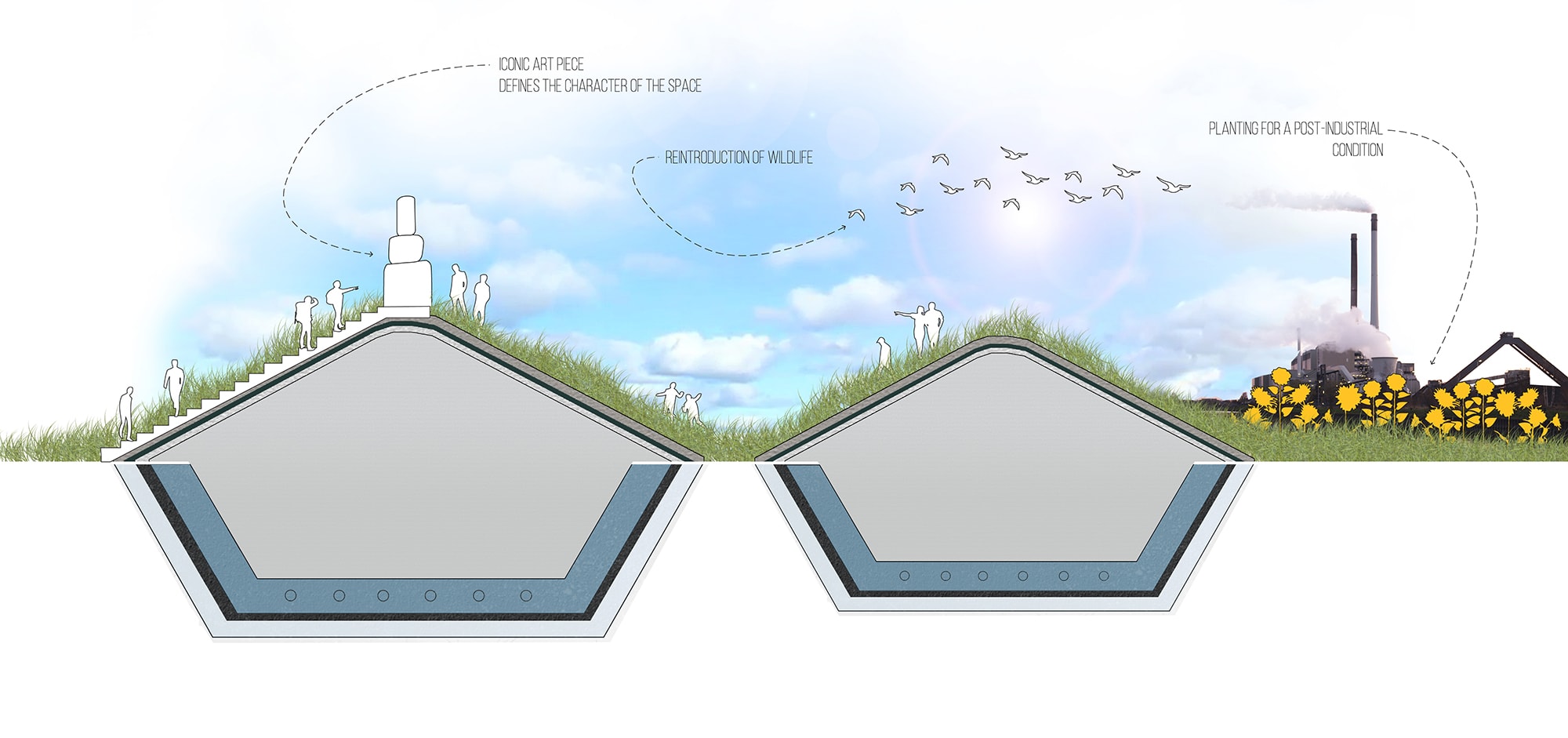

Artful Wastescape. Exploration of creative landfill strategies to build an iconic landscape. While landfills will most effectively contain heavy metals, they should be designed for human interaction. Images by Lauren Delbridge

Artful Wastescape. Exploration of creative landfill strategies to build an iconic landscape. While landfills will most effectively contain heavy metals, they should be designed for human interaction. Images by Lauren Delbridge

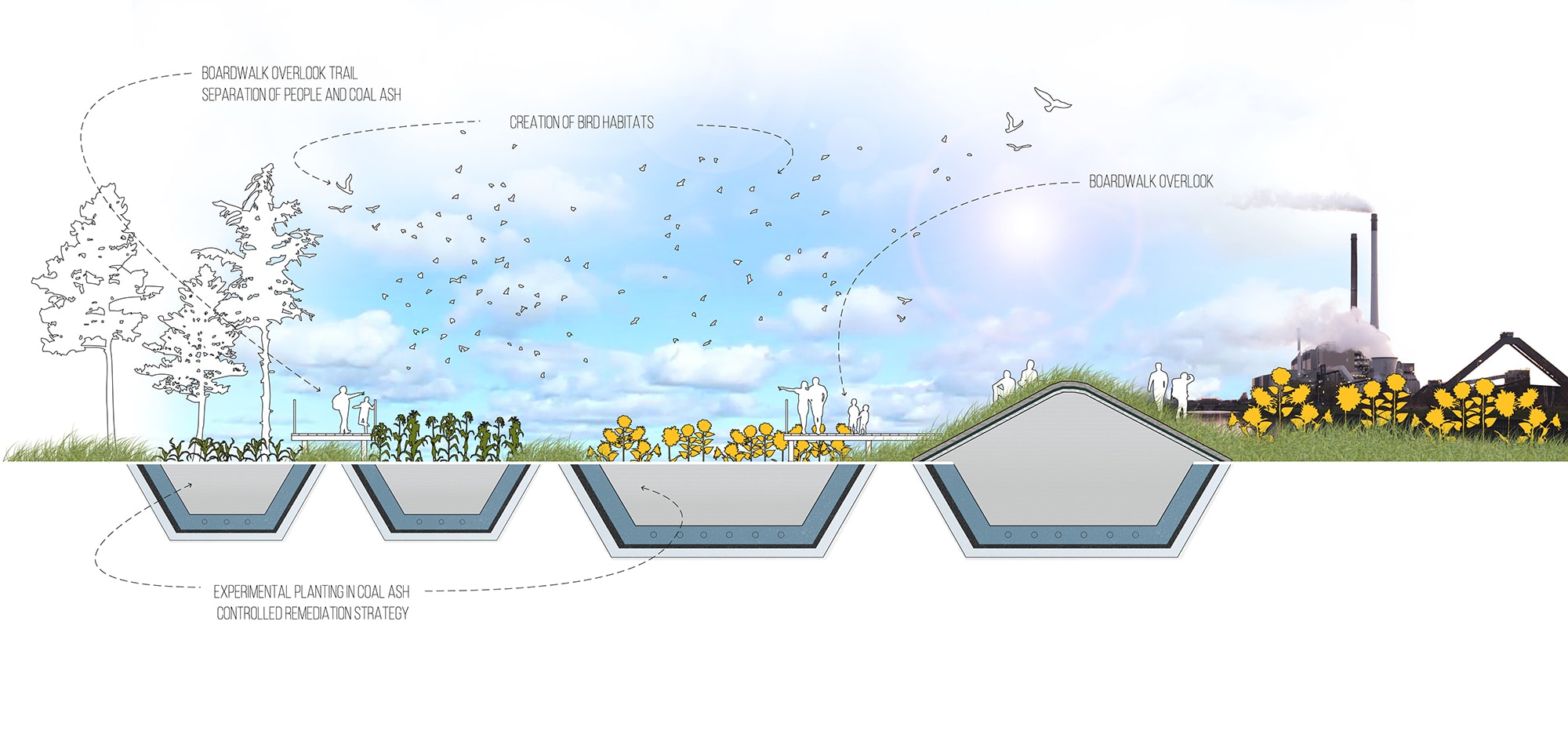

Remediated Ecologies. Exploration of in-situ remediation techniques to recreate habitats for species long forgotten on site. Coal ash contains organic matter suitable for experimental planting. Images by Lauren Delbridge.

Remediated Ecologies. Exploration of in-situ remediation techniques to recreate habitats for species long forgotten on site. Coal ash contains organic matter suitable for experimental planting. Images by Lauren Delbridge.

Creative Waste Disposal Precedents

Although there are no precedent examples of transformed coal ash pond sites, there are numerous global examples of creative waste disposal strategies. Recent travels to the Ruhr Valley in Germany revealed particularly interesting outlooks on waste and the activation of wastescapes. This industrial region of Germany is celebrating the history of industry — coal in particular — even bringing attention to the byproducts of their industrial successes. It is critical to take cues from how other countries are handling the by-products of their power dependencies.

Beckstraße Tip + Tetraeder, Bottrop. Mining spoil from the adjacent coal mine is left in a mountainous pile. This spoil tip encourages visitors to climb to the summit to experience its iconic “Tetraeder” sculptural landmark. Images by Lauren Delbridge

Beckstraße Tip + Tetraeder, Bottrop. Mining spoil from the adjacent coal mine is left in a mountainous pile. This spoil tip encourages visitors to climb to the summit to experience its iconic “Tetraeder” sculptural landmark. Images by Lauren Delbridge

Zollverein, Essen. Coal mine and coking plant turned UNESCO World Heritage Site. The site digs into the industrial history of the Ruhr region of Germany, and educates the public on the processes that took place within its walls. Images by Lauren Delbridge

Zollverein, Essen. Coal mine and coking plant turned UNESCO World Heritage Site. The site digs into the industrial history of the Ruhr region of Germany, and educates the public on the processes that took place within its walls. Images by Lauren Delbridge

Himmelstreppe, Gelsenkirchen. A former colliery site and spoil tip scattered with sculptural remnants of the industrial past. The peak of the spoil tip is apocalyptic; devoid of vegetation and topped by an overwhelming sculpture. Images by Lauren Delbridge

Himmelstreppe, Gelsenkirchen. A former colliery site and spoil tip scattered with sculptural remnants of the industrial past. The peak of the spoil tip is apocalyptic; devoid of vegetation and topped by an overwhelming sculpture. Images by Lauren Delbridge

Where are we going?

“People think coal ash is not going to be a problem because utilities are switching to natural gas and it’s cleaner,” says Avner Vengosh, a geochemist at Duke University who studied the Kingston and Dan River spills. “But the legacy of coal ash production and disposal is going to be with us for ages. These contaminants don’t biodegrade [7].”

We have long overlooked the issue of coal ash ponds and have been unwilling to face the consequences of our coal-fired power dependency. We have spent decades covering up our problem — hiding ash in ponds and basins behind fences and barricades. We have stripped our mountains for coal, burned tons upon tons of coal to generate power, and dumped the waste into vulnerable landscapes and communities. Now is the time to take back the land these power stations have desecrated and transform the waste into landscapes that give back to the environment and their surrounding communities.

Lauren Delbridge received her Bachelors of Landscape Architecture from Virginia Tech, where she was first introduced to the issue of coal ash ponds. Her work with these sites earned her the 2017 Undergraduate National Olmsted Scholar award from the Landscape Architecture Foundation. Lauren has continued to be involved with the Landscape Architecture Foundation, recently completing the 2018-2019 LAF Fellowship for Innovation and Leadership where she continued to investigate the future of coal ash ponds. Lauren currently works as a landscape designer for LandDesign in Charlotte, NC.

Lauren Delbridge received her Bachelors of Landscape Architecture from Virginia Tech, where she was first introduced to the issue of coal ash ponds. Her work with these sites earned her the 2017 Undergraduate National Olmsted Scholar award from the Landscape Architecture Foundation. Lauren has continued to be involved with the Landscape Architecture Foundation, recently completing the 2018-2019 LAF Fellowship for Innovation and Leadership where she continued to investigate the future of coal ash ponds. Lauren currently works as a landscape designer for LandDesign in Charlotte, NC.

Notes

[1] 2017 Coal Combustion Product Production & Use Survey Report. PDF. Farmington Hills, MI: American Coal Ash Association. 2018.

[2] “Chesterfield Power Station.” Chesterfield Power Station | Dominion Energy. Accessed October 15, 2018. https://www.dominionenergy.com/company/making-energy/coal-and-oil/chesterfield-power-station.

[3] “Coal Ash Disasters.” Appalachian Voices. Accessed March 10, 2019. http://appvoices.org/coalash/disasters/.

[4] “Disposal of Coal Combustion Residuals from Electric Utilities.” EPA. March 13, 2019. Accessed April 15, 2019. https://www.epa.gov/coalash/coal-ash-rule.

[5] Larson, Aaron. “Coal Combustion Residuals Rule Compliance Strategies.” POWER Magazine. 31 May 2016. Accessed 15 September, 2016. http://www.powermag.com/coal-combustion-residuals-rule-compliance-strategies/.

[6] Coal Combustion Residuals Impoundment Assessment Reports. PDF. EPA, June 24, 2016.

[7] “Coal’s other dark side: Toxic ash that can poison water and people.” National Geographic. February 19, 2019. Accessed August 2, 2019. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/2019/02/coal-other-dark-side-toxic-ash/

[8] Coal Blooded. Putting Profits Before

Cite

Lauren Delbridge, “Coal Ash Wastescapes: The Byproduct of Our Coal-Fired Power Dependency,” Scenario Journal 07: Power, December 2019, https://scenariojournal.com/article/coal-ash/.