Decolonization is a complex and multifaceted process that involves examining and denouncing colonialism; recovering and adopting Indigenous knowledge, language and practices, and; undertaking scholarly projects that address the needs of Indigenous communities [1]. In their essay “Decolonization is Not a Metaphor,” Eve Tuck and Wayne Yang stress that decolonization should inform radical politics that dismantle colonial relations and settler privileges, as well as involve projects that advance the repatriation of Indigenous life and land [2]. Others, such as Waziyatawin and Michael Yellow Bird, argue that, “first and foremost, decolonization must occur in our own minds” [3]. Research is an important vehicle in this process of developing a new consciousness. In particular, research that foregrounds the systemic and ongoing oppression of Indigenous ways of knowing, as well as scholarly projects that engage in reimagining the world through alternative visions and possibilities [4].

Exemplified by the rise of the ‘Water is Life’ movement, water has emerged as a key agent and site of contestation in the struggle for decolonization [5]. Zoe Todd, for instance, points out that “Rivers invited colonial movement into Indigenous territories throughout the historical colonial period in North America. And today, rivers also invite resistance to colonialism” [6]. Todd’s work frames the river as a terrain and narrative device that brings colonial and Indigenous ways of being in relation to each other. In this context, the role of infrastructure cannot be separated from the construction and reconfiguration of power dynamics. The history of dam construction, channelization, urban development, and management of rivers are intertwined with violent displacement and erasure of Indigenous knowledge and practices, as well as complex legal frameworks and land rights. As social movements to address the inequities and injustices done to Indigenous communities (and other minorities) intensify, it is critical to confront the legacies of colonial infrastructures and public works that continue to shape contemporary landscapes, ecologies and social relations. “Critically questioning the colonial practices of planning, architecture, and engineering,” according to Pierre Bélanger, “seeks to contribute a basis for undermining the industrial underpinnings and imperialist hegemonies that lie on, above, and below the surface of contemporary settler-state space whose foundations rely and rest on the perpetuation of spatial inequities, environmental injustices, and cultural inhumanities” [7].

These patterns of colonial infrastructure planning are on full display in the Missouri River Basin—a system of engineering works that inundated over 356,000 acres of Indigenous lands,[8] transformed one-third of the Missouri River ecosystem into lake environments, and helped shape the agricultural Midwest that we know today. Despite its many exploitations, the Missouri River continues to flow and permeate spatial relations and legal systems. Whether through periodic floods and droughts, or through contesting developments that threaten its ways of being, the river and its water protectors remind us of the complex web of colonial and decolonial relations shaped by its existence. In this context, this essay focuses both on ways in which designers can begin to grapple with the violence enacted through colonial water infrastructures in the Missouri River, as well as ways to envision alternative futures where water—in its spiritual, material, and legal dimensions—becomes an agent of resistance that can shape new human and more-than-human relationships. In doing so, it provides a small step in developing designerly ways of approaching water as, in the words of Melanie K. Yazzie and Cutcha Risling Baldy (2018), “a relative with whom we engage in social (and political) relations premised on interdependency and respect” [9].

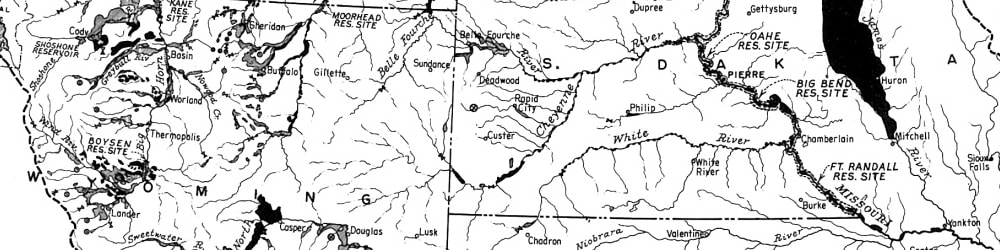

Relationship between the six major dams and reservoirs in the Mainstem of the Missouri River and Native American Reservations in the Missouri River Basin. Image by Kees Lokman.

The Missouri River Basin

Covering over 500,000 square miles and extending across ten U.S. states, two Canadian provinces, and 29 Native American Reservations, the Missouri River Basin holds a wealth of natural resources, provides nearly half of U.S. wheat, a quarter of its corn, and holds a third of its cattle with an annual value of $100 billion. It is one of the most important and contested interior watersheds of North America. Many existing land uses in the basin would not be possible if not for the implementation of the Pick-Sloan Plan, which drastically altered water flows in the basin for the purposes of flood control, water supply, irrigation agriculture, energy developments, navigation, and recreation.

The Pick–Sloan Plan, authorized in 1944, is a forced marriage of separate Missouri River development plans prepared by the Bureau of Reclamation and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Responding to a long history of floods in the basin—most significantly the 1943 Missouri River flood—the plan by the Corps of Engineers, led by Colonel Lewis Pick, prioritized the construction of dams and reservoirs in the mainstem of the Missouri River to provide flood storage and aid navigation in the lower basin. William Glenn Sloan was in charge of preparing the plans for the Bureau of Reclamation, whose primary goals were irrigation development and hydroelectric power generation. The Bureau’s plans included over ninety dams and reservoirs across the basin, along with several hundred irrigation projects, doubling the basin’s irrigated acreage [10].

While the full extents of the Pick-Sloan Plan where never entirely carried out, the basin’s landscape—its hydro-ecological, cultural, and economic processes—have irreversibly changed. In particular, the project continues to have catastrophic effects on to the livelihoods and lands of Indigenous communities. Despite the existence of the U.S Indian Law and the Treaty of Fort Laramie, which protected the rights of tribal nations to their land and water, The Corps of Engineers and Bureau of Reclamation seized the land through eminent domain. Subsequent construction of numerous dams and reservoirs in the Missouri River mainstem (including Fort Peck Dam, Garrison Dam, Lake Sakakawea, Oahe Dam, Big Bend Dam, Fort Randall Dam, Gavins Point Dam, and Lewis and Clark Lake) flooded nearly 1.5 million acres. Nearly a quarter of this land belonged to Native Americans groups, including the Arikaras, Chippewas, Mandans, and Hidatas of North Dakota; the Shoshones and Arapahos of Wyoming; and the Crows, Crees, Blackfeet, and Assiniboines of Montana.

Settler privilege and cost savings were the main drivers of site selection and decision-making. As pointed out by Robert Kelley Schneiders, “Engineering considerations were a factor in the site selection and design of Pick-Sloan dams, but political considerations, especially a concern for maintaining the Pick-Sloan compromise and sparing off-reservation urban centers, were the primary reasons the dams and reservoirs were designed to be so high and built at locations so disadvantageous to Indian interests” [11]. While the ecological significance of the floodplains, and its importance for Indigenous ways of life, had been documented as early as the Lewis and Clark Expedition, widespread imagery of dam construction and the harnessing of nature through technology fostered social imaginaries of the technological sublime. In doing so, the presence of Indigenous peoples and other living systems were effectively erased from these lands. As asserted by Jane Griffith: “This form of professional communication reveals how hydroelectric dams are built with more than engineering equipment—their tools also include narratives, language, rhetoric, and image that recast Indigenous waterways for settler audiences” [12].

Indigenous communities, who used the fertile floodplains of the Missouri River and its tributaries as a source of sustenance, a method of transport, and a vital part for ceremonial activities, were forced to relocate to barren upland regions. The devastation caused by this illegal act of displacement continues to impact every aspect of Indigenous ways of life—from food sovereignty, economic development, and education to mental health, kin relations, and intergenerational knowledge sharing. Historian and activist Vine Deloria, Jr., a member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, described Pick-Sloan project as “the single most destructive act ever perpetuated on any tribe by the United States” [13].

Over the past decade, a number of key events, including the Missouri River Floods of 2011 and 2019, record droughts in 2012, the Bakken Formation fracking boom, and protests surrounding the Keystone XL and Dakota Access Pipelines in 2016, have underlined the need to reconsider relationships among water, infrastructure, Indigenous sovereignty, and the land. The following sections include a discussion of work conducted during a landscape architecture studio, “Fluid Geographies: Liquid Plans for the Missouri River Basin,” taught by the author at the University of British Columbia in Fall 2018. The studio engaged with the themes mentioned above and speculated on alternative water resource management strategies that acknowledge the rich histories and stories tied to the Missouri River Basin while embracing the more-than-human beings that inhabit these lands [14]. The author acknowledges that various Indigenous communities rely on the Missouri River and that each community has their specific histories, technologies, and associations with the river. The studio sought to be mindful of how these different ways of relating to water could be incorporated in the proposals.

Design Approaches

What follows is a discussion of three design projects from this studio. In Actions to Express Claim—Water, Sam McFaul explores potential changes to the legal infrastructure that would enable Native American Reservations to utilize their land by creating a series of on-the-ground actions to legitimize their claim. Sovereign-Pte by Emily Soder-Duncan and Karen Tomkins seeks to promote food sovereignty for the Nakoda and A’aninin on the Fort Belknap Reservation in central Montana by acquiring land for bison reintroduction and prairie restoration. And Unceded by Jasmine Cress, Tory Michak and Tatiana Nozaki, proposes a series of interventions that follow along the route of the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL), revealing how its contentious existence has inflicted social and environmental grief.

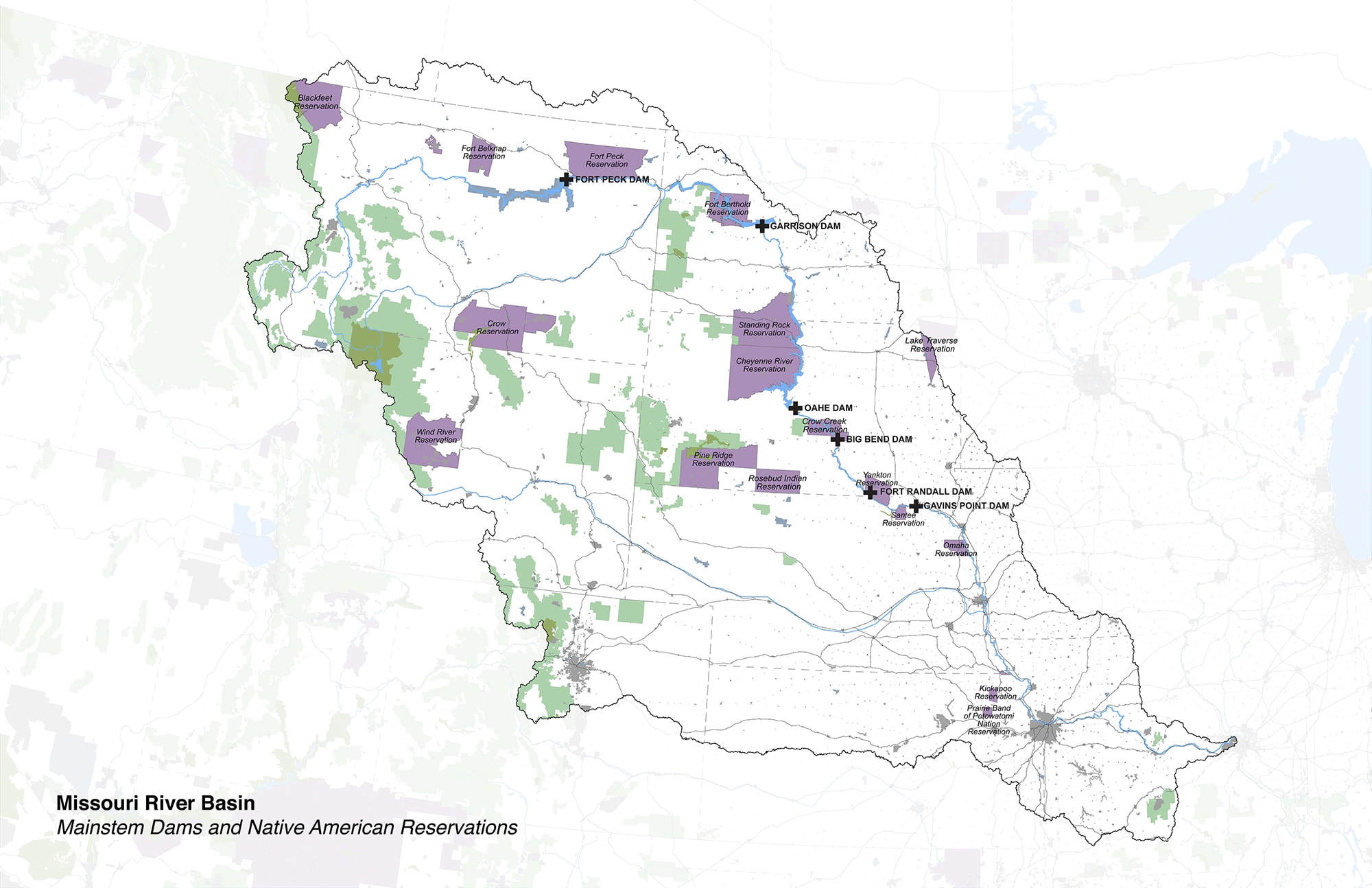

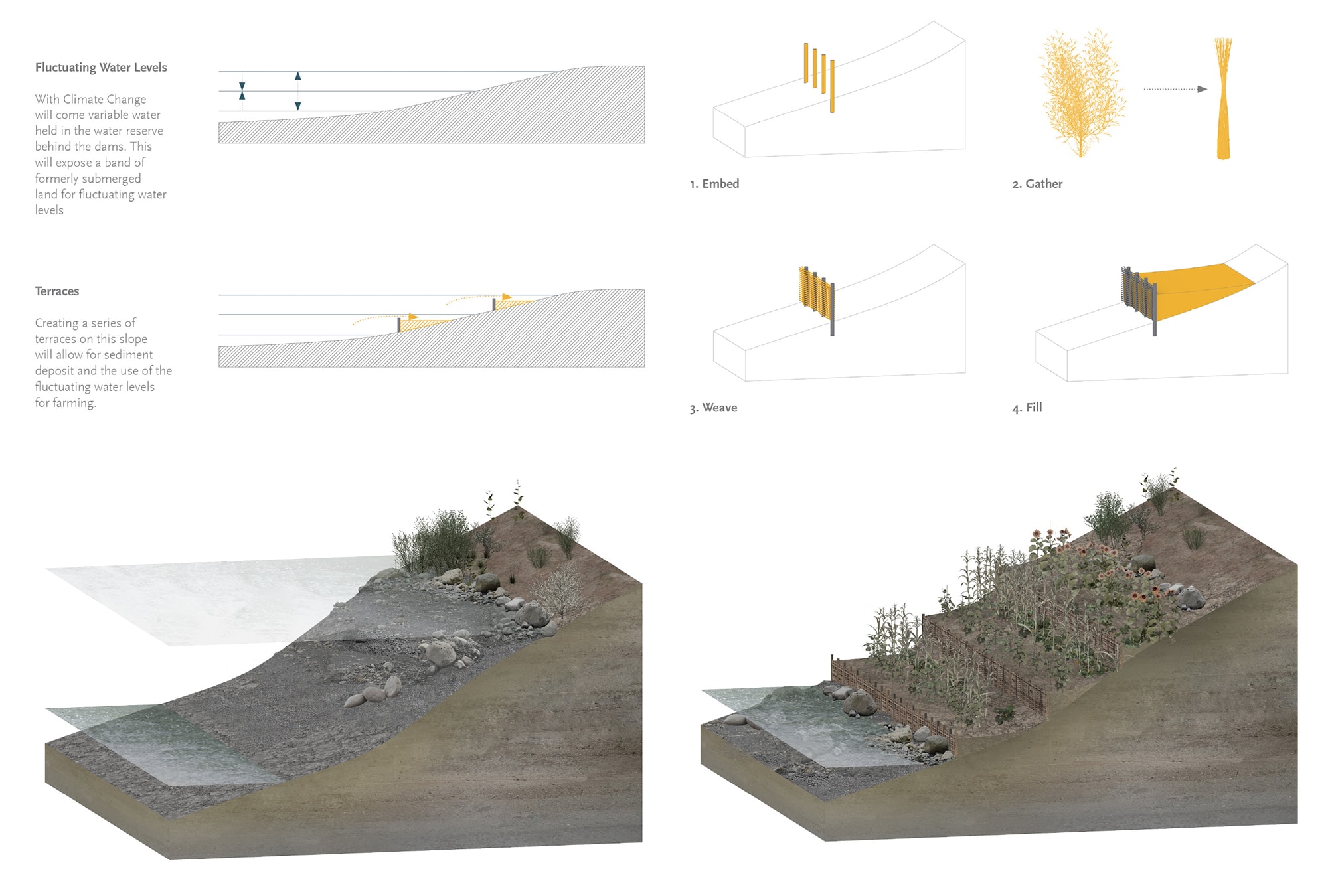

Timeline of Native American Water Rights in the United States. Image by Sam McFaul.

Actions to Express Claim—Water

This proposal explores the role and agency of design and representation in relation to ways in which Native American groups can act upon their water rights in the Missouri River Basin. It examines the spatial implications of the histories, and possible alternative futures, of legal rules which govern the allocation of surface waters for consumptive uses along the Missouri River and its tributaries.

In the United States, Indigenous groups, together with the federal and state governments, municipalities, and industries, can assert claims over water. No one entity can establish all of the rules, especially in cases involving interstate, cross-region, and cross-jurisdiction water disputes [15]. Depending on the nature of the conflicts and claims, the Supreme Court of the United States decides on a case-by-case basis over the use of water from an interstate stream. A reasonably good description of the aspects taken into consideration when decisions are made over water claims is provided in Nebraska v. Wyoming (1945):

“Priority of appropriation is the guiding principle. But physical and climatic conditions, the consumptive use of water in the several sections of the river, the character and rate of return flows, the extent of established uses, the availability of storage water, the practical effect of wasteful uses on down-stream areas, the damage to upstream areas as compared to the benefits to downstream areas if a limitation is imposed on the former—these are all relevant factors. They are merely an illustrative, not an exhaustive catalog. They indicate the nature of the problem of apportionment and the delicate adjustment of interests which must be made” [16].

Since Indigenous groups own substantial areas of land directly adjacent to the Missouri River and its principal tributaries, they have legitimate claimants to reserved water tights. Much of these rights have currently not been exercised due to the complex nature of claims over water [17]. This complexity is driven by the fact that existing water rights and law are mostly derived from issues in the Colorado River basin, which are guided by aspects of water scarcity. However, the challenge of the Missouri River basin concerns negotiating between often not having enough water (in the upper basin), and too much water (in the lower basin). In addition to allocating a specified quantity of water for use, which makes sense in areas of water scarcity, there is a case to be made Indigenous groups have the rights to the flow of the river in those areas of relative abundance. Environmental lawyer John Davidson, who has written extensively about water conflicts in the Missouri River basin, suggests: “[Indigenous groups] are compelled to argue that since it is the abundant flow that is generating economic benefits, tribes must, like any other property owner, be allowed to determine how the flow is to be used and directly enjoy the economic benefits created by that use” [18].

Within this context, the proposal Actions to Express Claim—Water, speculates on a set of architectural responses that begin to lay claim on the land and water sources in and adjacent to the Missouri River. These explorations do not inherently suggest specific sites, but rather a set of potential actions and tactics that work both with and against the colonial laws and infrastructures as a means to recover and develop new social-ecological relations with the river. These actions are divided in four broad themes: 1) environment: climate change and ongoing physical changes to the geography as a driver for laying claim; 2) tradition: application of Indigenous practices to lay claim; 3) industry: using the logic of capitalism to lay claim, and; 4) protest: laying claim through activism and dissent. McFaul developed a range of possible actions in each of these categories. I have chosen to highlight one example in within each theme to indicate a range of potential actions.

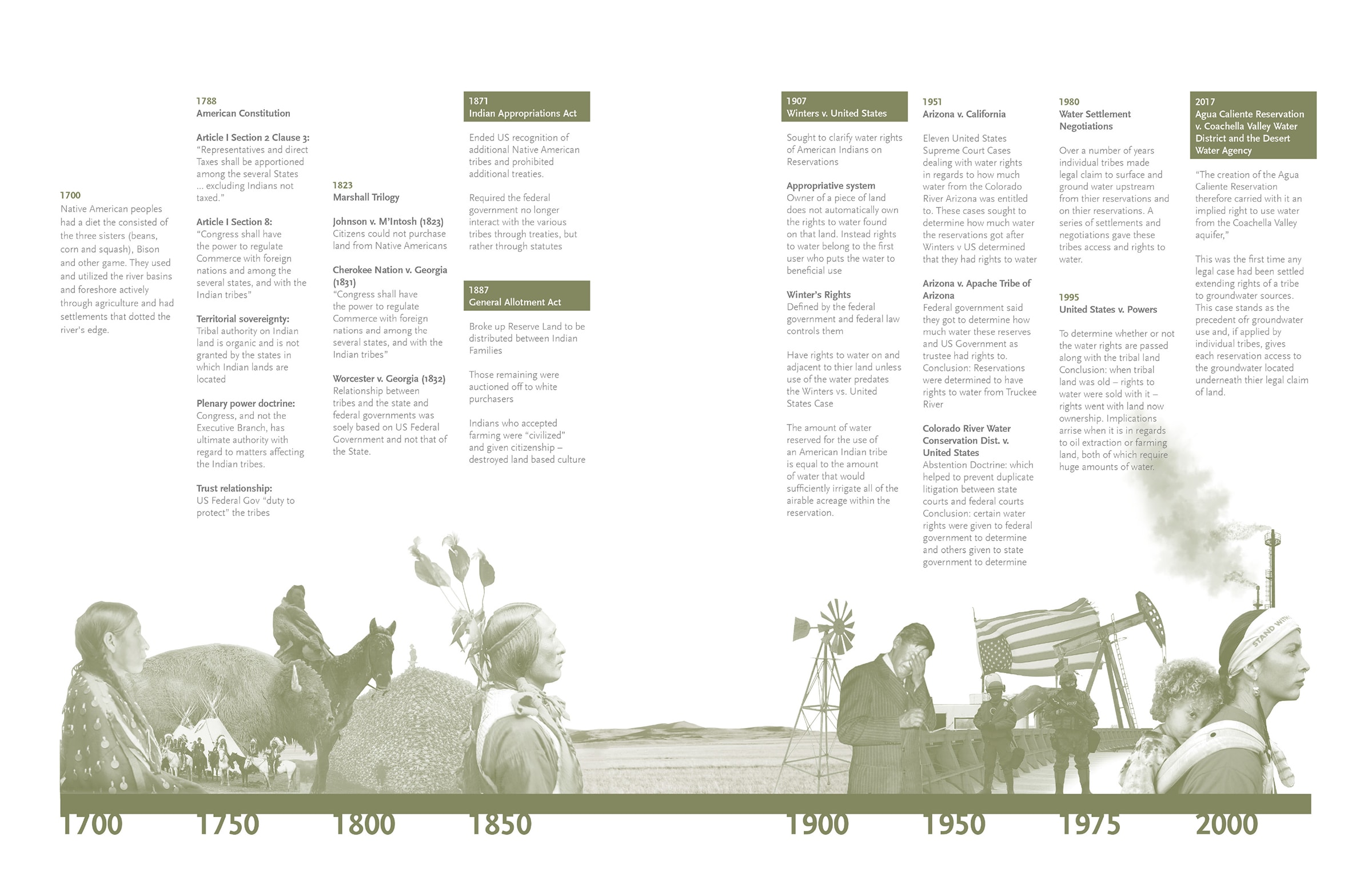

Retain uses low-tech solutions to create terraces at the edge of the reservoirs for the cultivation of food resources. Drawings by Sam McFaul

Environment

With climate change, the projected amount of water in the reservoirs behind the six dams in the Missouri River will drastically change [19]. Retain speculates on potential futures for the area of land that may be exposed in the event of prolonged droughts, and a subsequent drop in water levels of the reservoirs. It asks the question: To whom does this land, water and sediment belong? The action uses a traditional wattle method by which Salix Sitchensis (willow) is woven into a natural retaining wall. With fluctuation of the water levels, these retaining walls can capture and retain sediment. The terraces created by these interventions can be used for the cultivation of a wide range of different food crops and medicinal plants. In doing so, it provides a mechanism for Indigenous communities to lay claim to both the water and the newly created land.

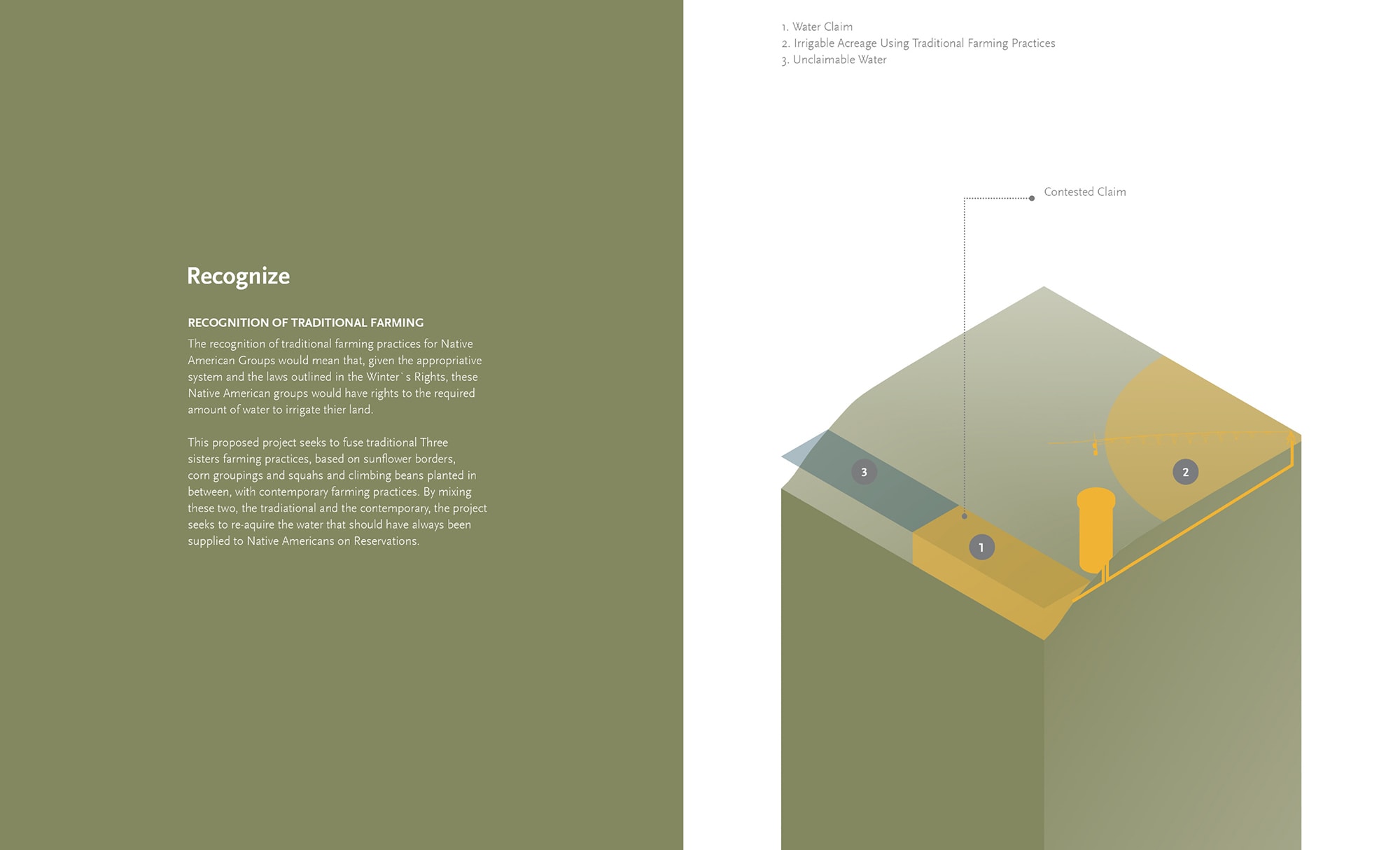

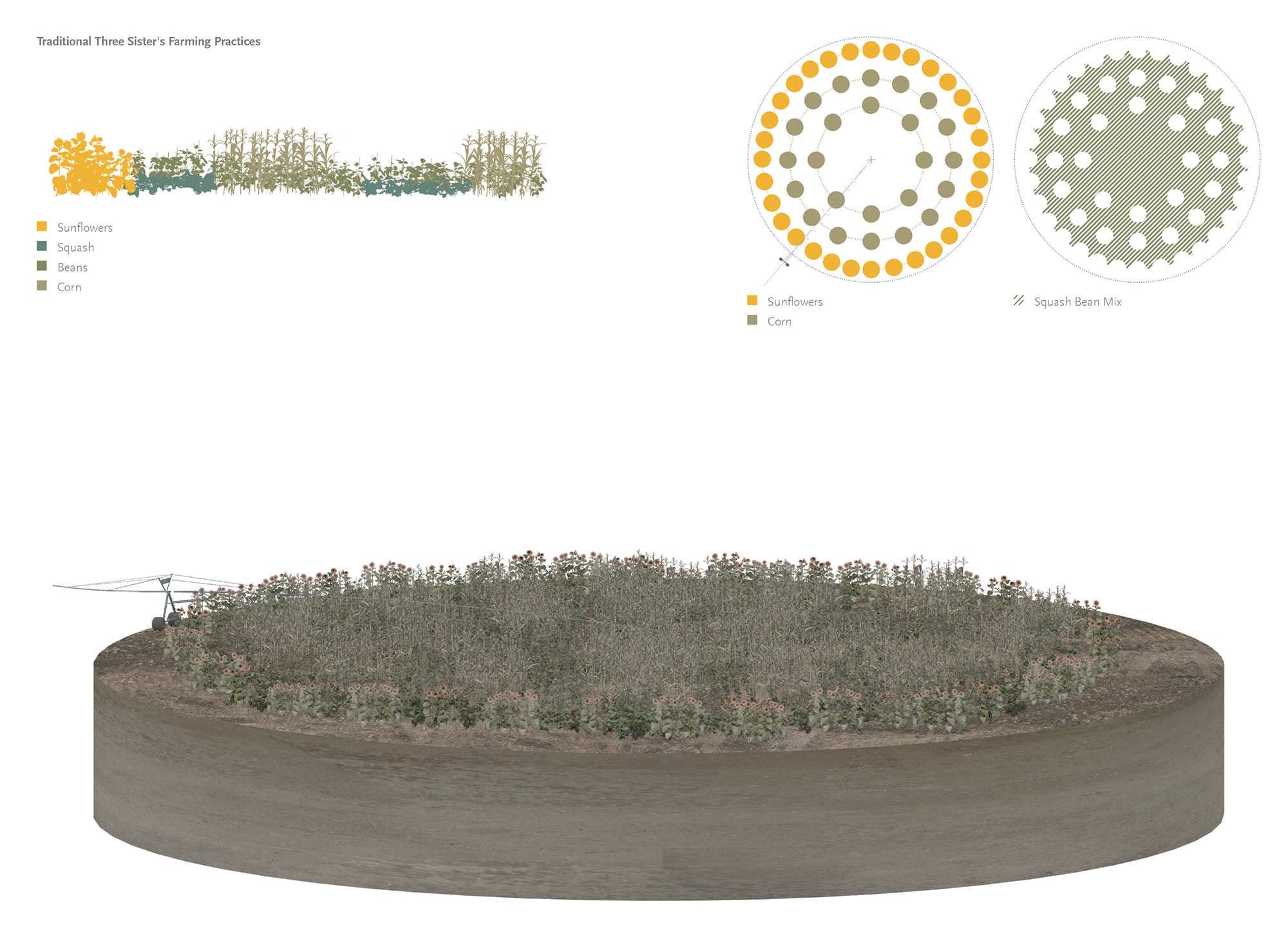

Recognize appropriates colonial irrigation infrastructure to recover and expand Indigenous food cultivation. Drawings by Sam McFaul

Tradition

Recognition of Indigenous farming practices would mean that, given the appropriative system and the laws outlined in the Winter’s Rights, Indigenous groups can claim rights to the required amount of water to irrigate these lands critical for enabling food sovereignty. This proposed action fuses the traditional practices of Three Sisters, which combine maize (corn), winter squash, climbing beans, and other Sisters, like sunflowers or amaranth, with the contemporary farming practices enabled by pivot irrigation. By hybridizing the traditional and the contemporary, this action seeks to re-acquire water that should have always been supplied to Indigenous groups along the Missouri River.

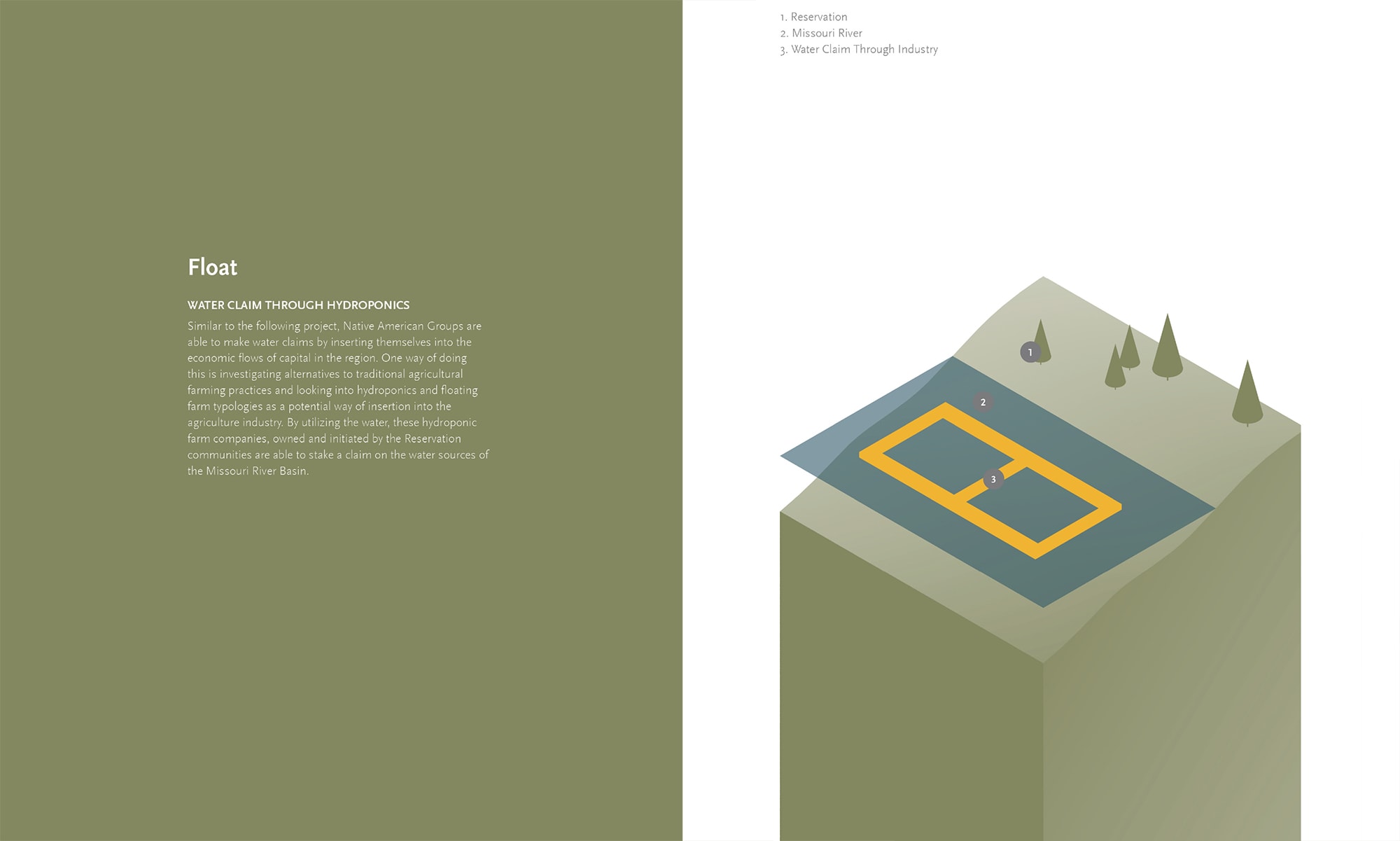

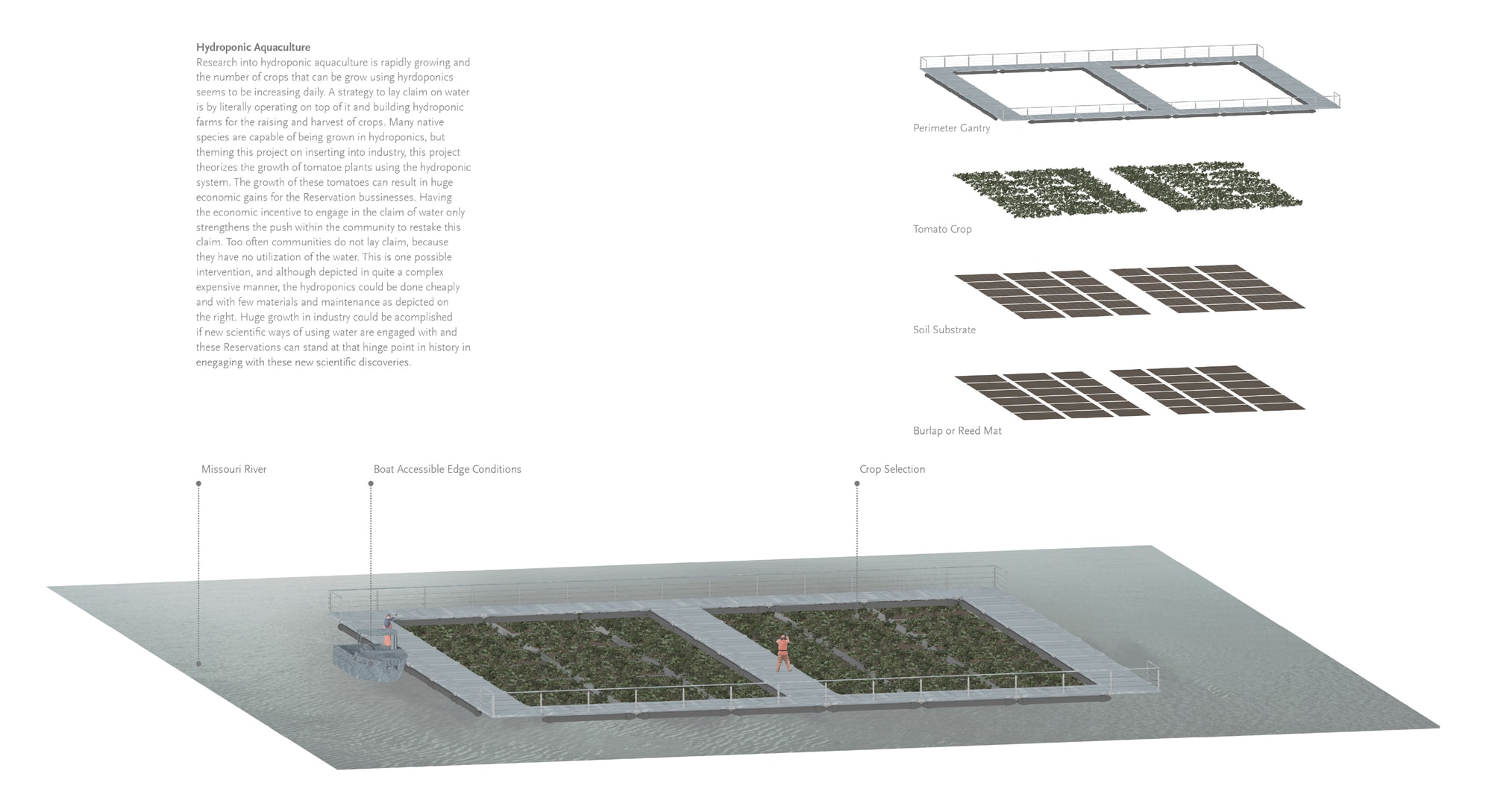

Float proposes claiming the flow of water as a means to develop aquaculture technologies. Drawings by Sam McFaul

Industry

Indigenous groups can also lay claim on the water in the Missouri River if they can demonstrate how its flow is used to generate economic benefits. One potential way of doing this is by exploring the implementation of aquaculture and/or floating farming practices within the reservoirs or river. While these practices may traditionally not have been part of Indigenous ways of life in the region, they can provide an avenue to develop new technologies, expertise, and business opportunities. Lake aquaponics could be implemented relatively cheaply, and beyond producing food and creating jobs, it could become an effective method to remove nutrients from the river.

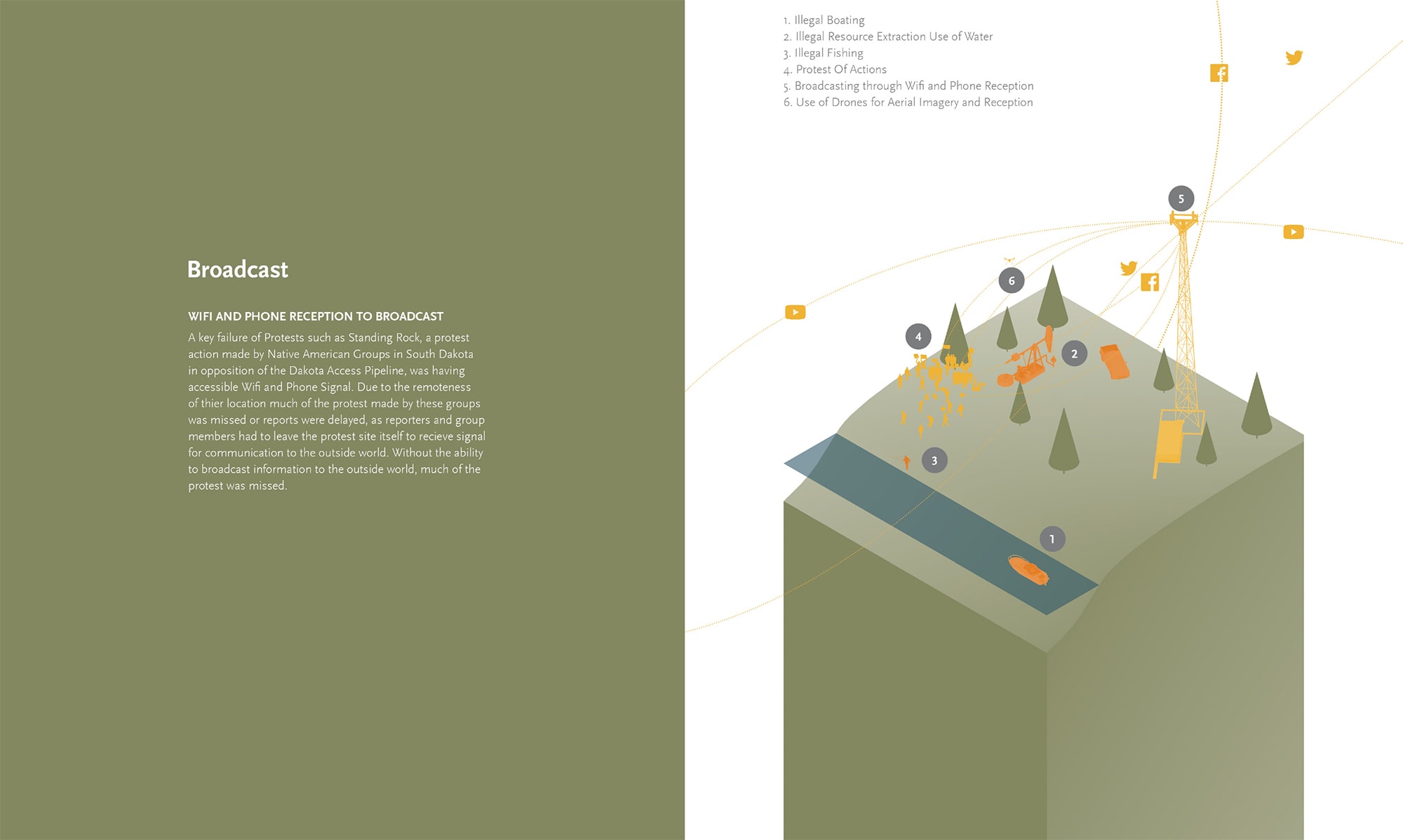

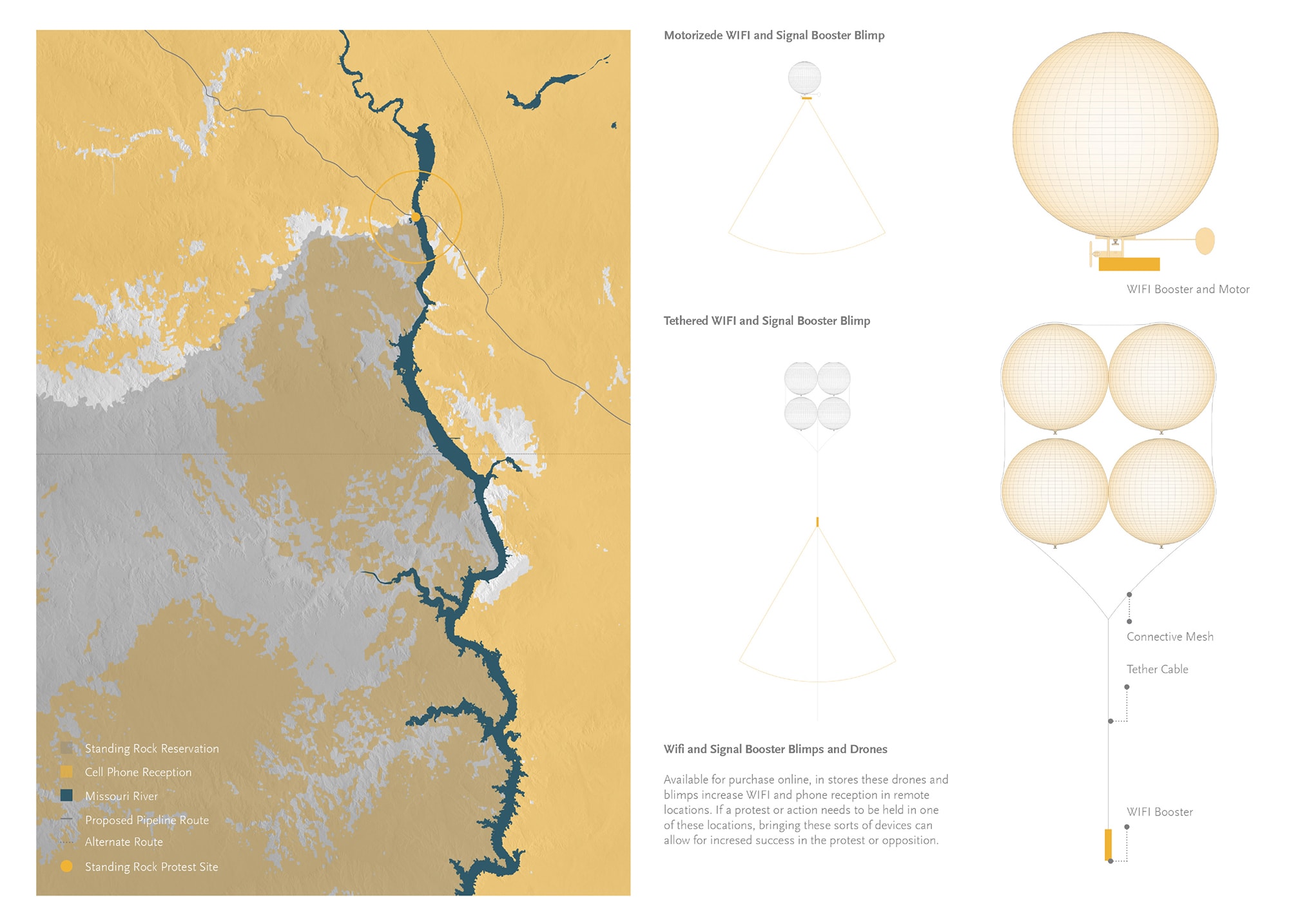

Low-tech devices and spatial interventions associated with the action: Broadcast. Drawings by Sam McFaul

Low-tech devices and spatial interventions associated with the action: Broadcast. Drawings by Sam McFaul

Protest

The last group of actions focuses on protest, which draws from both the success and challenges faced by the Standing Rock protest. One such strategy, involves designing low-tech electronic kits (with drones, blimps, and water monitoring equipment) that protestors can bring along to capture and document the protest, and potential violations against people and the environment. the is particularly important since many protests concern resource extraction and associated impacts of treaty violations and environmental degradation, which are often located in relatively remote areas out of reach from conventional telecommunication networks. Successful protests can help protect Indigenous sovereignty and stewardship over these waterways.

Taken together, McFaul’s proposed actions combine resistance, Indigenous knowledge, and design to challenge and subvert existing water rights. In doing so, it offers a range of different possibilities for building (new) relationships with the water that flows through the Missouri River and its territories.

Sovereign-Pte

Food sovereignty is defined as “the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agricultural systems. It puts the aspirations and needs of those who produce, distribute, and consume food at the heart of food systems and policies rather than the demands of markets and corporations” [20]. Food is a central component that weaves together cultural knowledge and traditions with environmental stewardship and ancestral relationships of Indigenous peoples with the land [21]. The ability of an Indigenous community or nation to make decisions about its food system requires that relations with lands, waters, plants and animals be sustained across multiple generations. When landscapes, ecosystems, and language is stripped away, and access to certain plants, animals, and practices are no longer available, a community loses critical components for its self-determination.

In this context, Sovereign-Pte provides strategies that seek to enable food sovereignty for the Nakoda and A’aninin on the Fort Belknap Reservation in central Montana by acquiring land for bison reintroduction as well as prairie restoration. Interventions focus on restoring river dynamics and fluctuations, food cultivation strategies, and Indigenous land management practices [22].

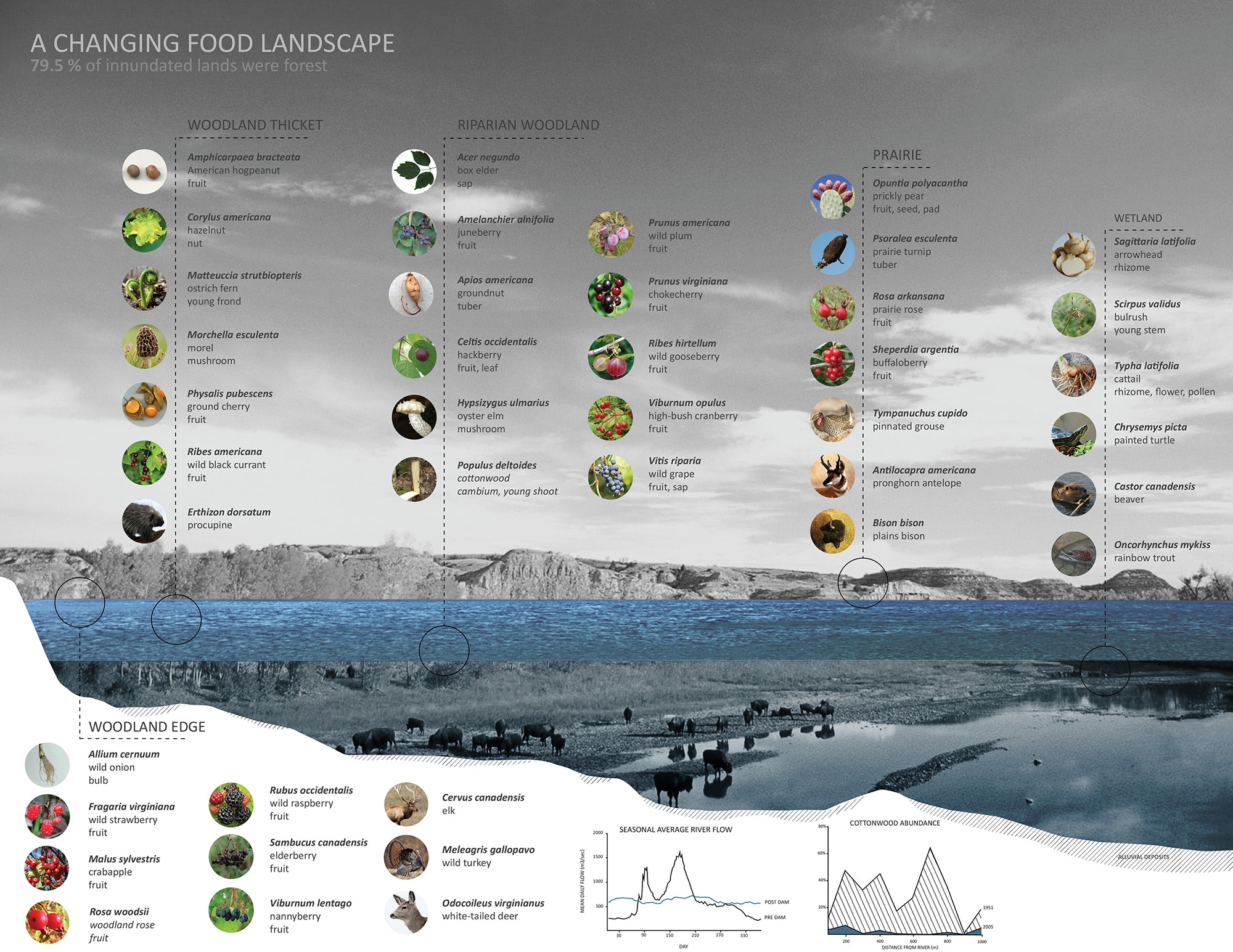

Habitats and associated food resources lost as a result of the construction of dams and reservoirs in the mainstem of the Missouri River, Drawings by Emily Soder-Duncan and Karen Tomkins

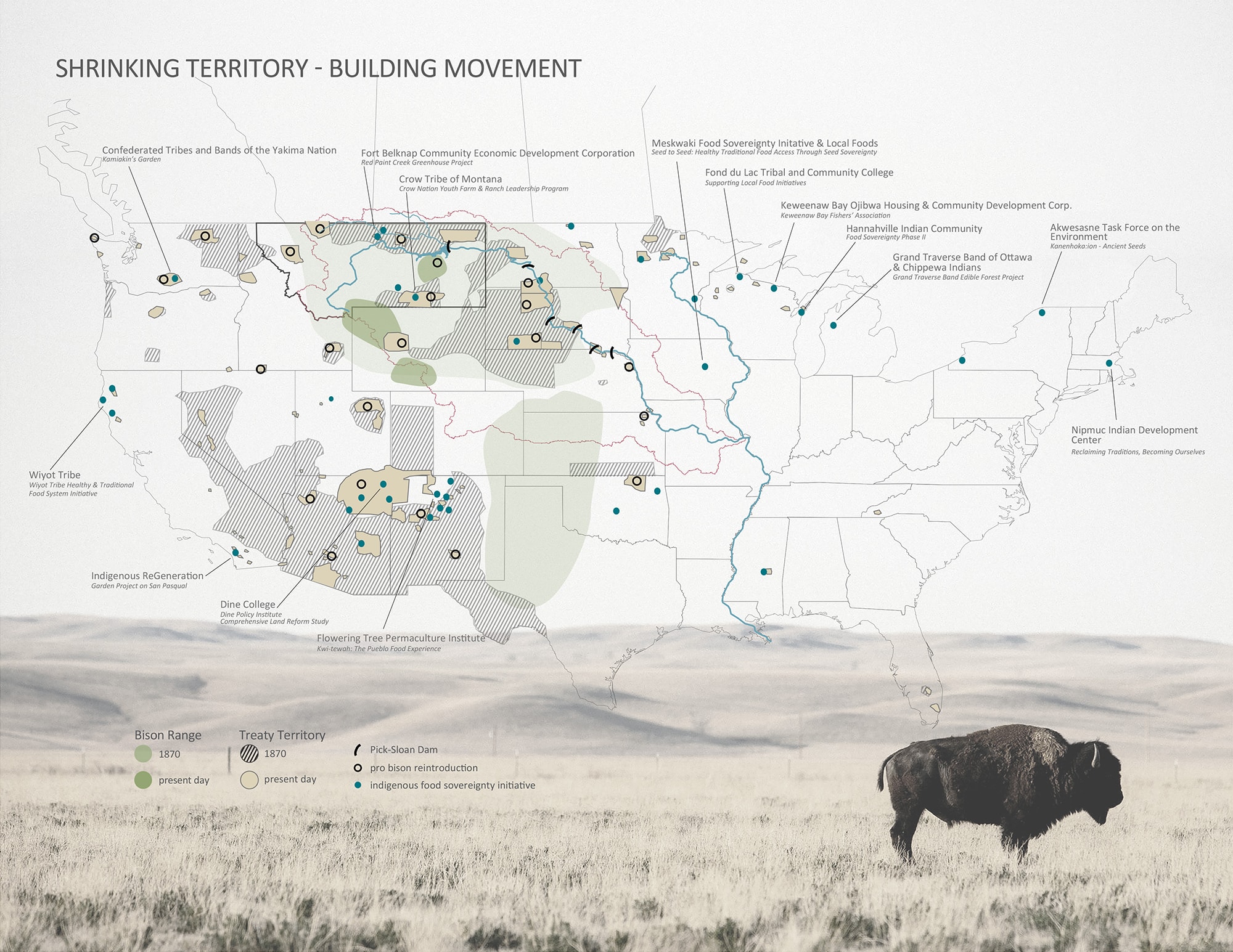

Native American-led Food Sovereignty movements across the continental United States. Drawings by Emily Soder-Duncan and Karen Tomkins

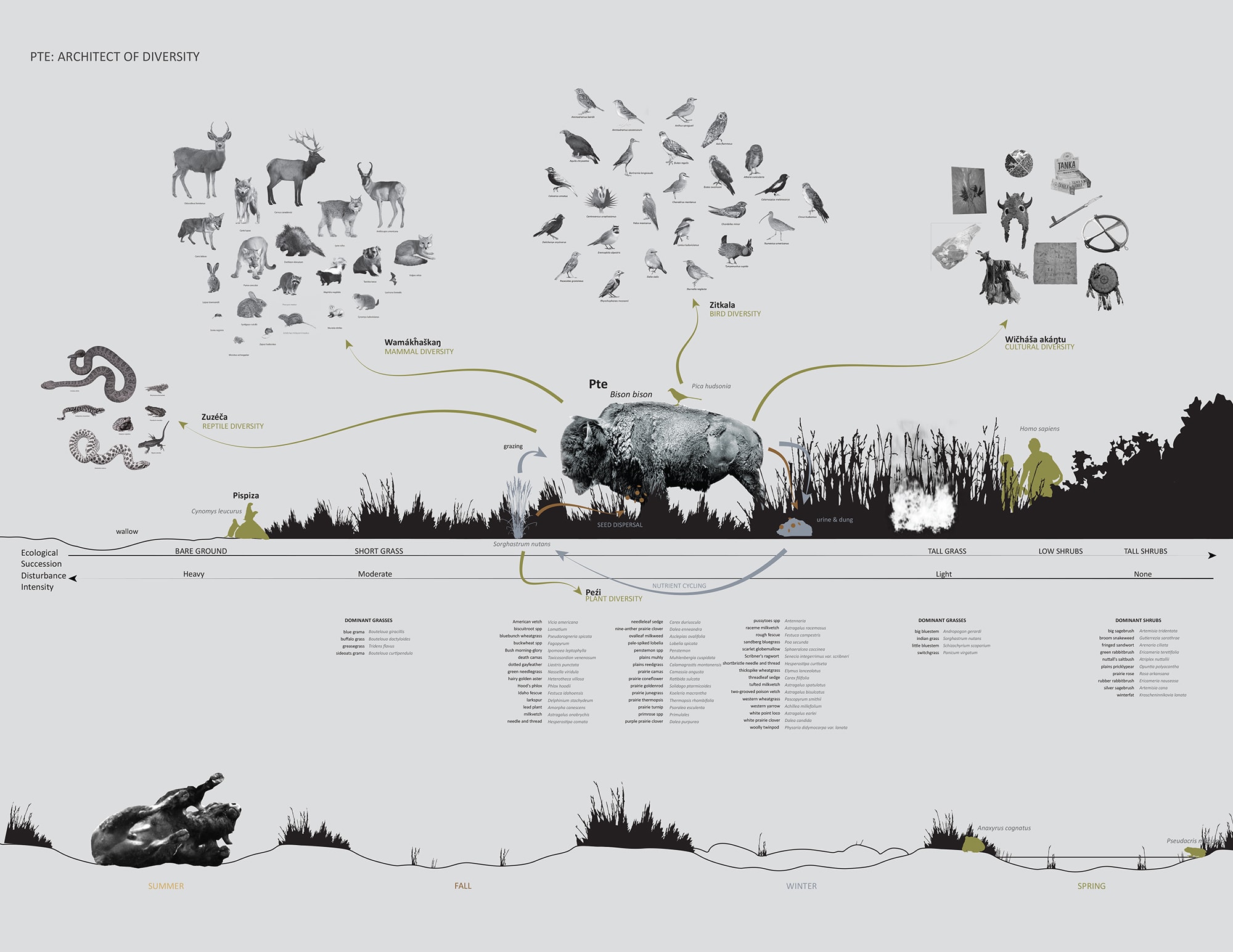

In the Missouri River Basin, much of the floodplains, riparian forests, and prairie ecosystems were drastically altered or destroyed as a result of settler colonialism, including the implementation of the Pick-Sloan Plan. This destruction combined with the uprooting and forceful relocation of Indigenous communities into Reservations continues to have major implications on personal wellbeing and cultural identity, including connections to ancestral lands, food sovereignty, and traditional knowledge. Of particular importance to the cultural identity of many of the Plains Indigenous peoples is their connection with the Bison (Pte in Lakota), which provided and cared for the people through food, shelter, clothing, tools, wisdom and more [23]. Bison, a keystone species on the prairie, are “architects of diversity,” and have co-evolved with the prairie over thousands of years [24]. They impact the land through grazing, wallowing, seed dispersal, and nutrient inputs, among others. Each of these activities provides inputs and/or disturbances that are vital for other species. Therefore, strategies aimed at reintroducing the bison are not only essential to recovering the cultural autonomy of Plains Indigenous peoples but also to the health of the prairie ecosystem as a whole [25].

The complex and multilayered relations of bison with human and non-human entities. Drawings by Emily Soder-Duncan and Karen Tomkins

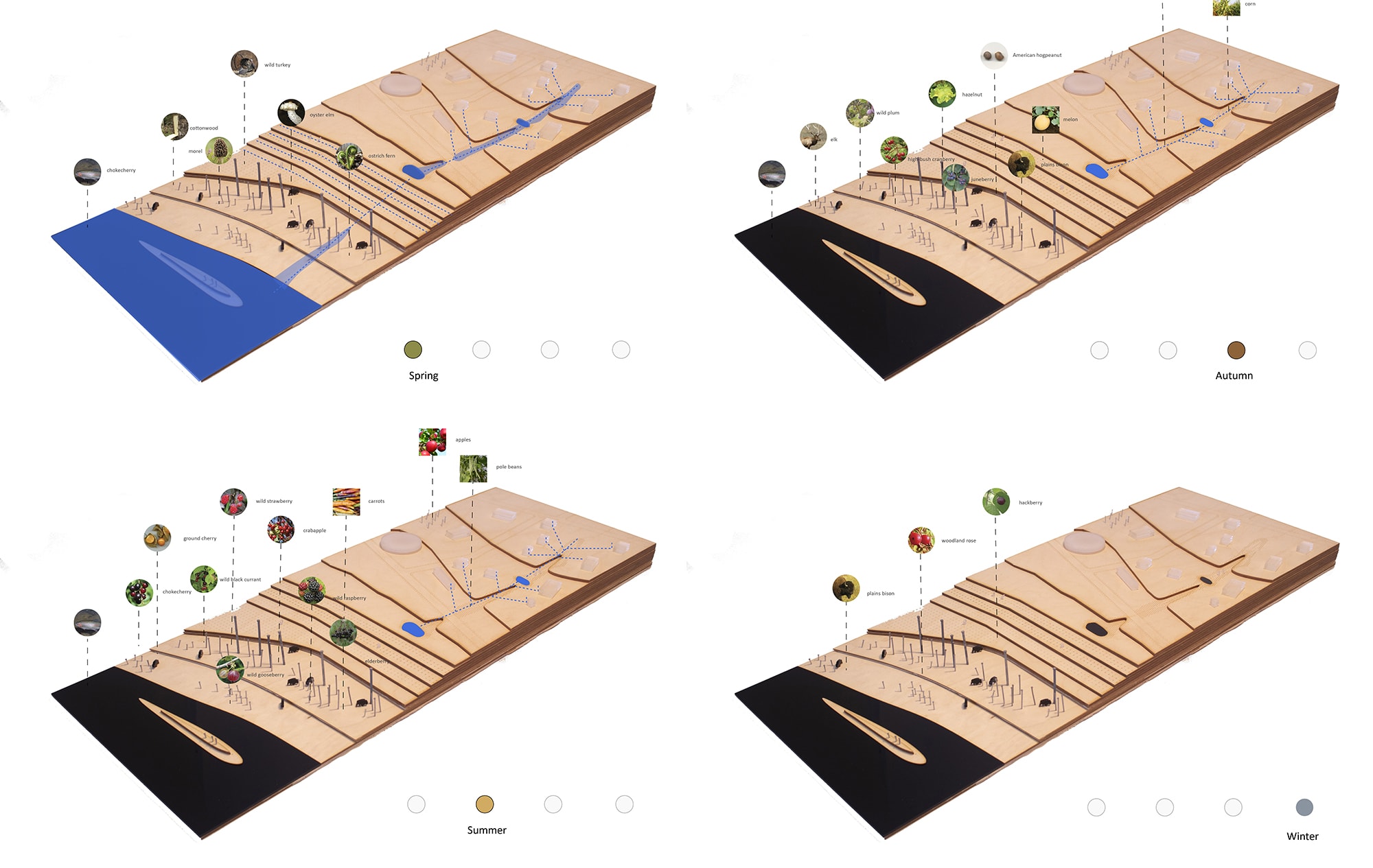

Food sovereignty and its relation to Indigenous knowledge and traditions, seasonal cycles, and land stewardship. Drawings by Emily Soder-Duncan and Karen Tomkins

Sovereign-Pte builds on ongoing efforts to ‘bring back’ bison in and around reservations in the Upper Missouri River Basin. In particular, the proposal seeks to support The American Prairie Reserve, a nonprofit focusing on creating a 3-million acre reserve by stitching together public lands through the purchase of private lands just south of Fort Belknap Reservation in Montana. The effort engages a diverse set of stakeholders, including those in tribal nations, government, conservation, and private landowners invested in realizing this vision of an interconnected habitat for free-roaming bison. Sovereign-Pte provides a range of design approaches and land management strategies to allow for the recovery and reconnection of bison and Indigenous practices.

The proposal specifically focuses on the community of Fort Belknap Agency, located adjacent to both the floodplain of the Milk River and shortgrass prairie. Removal of existing levees enables the dynamic forces of the river to regenerate riparian habitats, which host many plant and animal species vital to both bison and Indigenous communities. Proposed ha-ha walls have a dual function of acting as seasonal flood protection mechanism and a measure to prevent herds of free-roaming bison from entering the community. Stone terraces provide another opportunity for the combination of food production and water management. Fed by dry-swales that collect stormwater runoff as well as seasonal fluctuations of the river, the terraces provide opportunities for more intensely managed food practices.

Moreover, ecosystem restoration and the reintroduction of bison is essential for the recovery of traditional land management practice, including hunting, rotational burning, respectful harvesting, and pruning. Direct and sustained involvement in seeding, tending, and harvesting plants as well as hunting bison repairs and strengthens relations to the land. Borrowing the words of Charlotte Coté, Sovereign-Pte can be understood as a “decolonial praxis” and “restorative framework” that facilitates Indigenous self-determination and food sovereignty [26].

Section drawings showing a range of interventions to enable the recovery and reconnection of bison and Indigenous practices. Drawings by Emily Soder-Duncan and Karen Tomkins

Annotated models illustrating the shifting dynamics of water and the availability of food resources in the floodplain. Drawings by Emily Soder-Duncan and Karen Tomkins

Unceded

The final project, Unceded, consists of a series of interventions that follow along the route of the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) to reveal how its controversial existence has caused social grief and environmental degradation. Taking on an activist role, the interventions foreground the impacts of colonial infrastructure in unsettling tribal sovereignty, human and more-than human relations, and treaty rights. The proposal uses the lens of atonement as a means to confront those that encounter the interventions to question past and ongoing injustices embedded in the pipeline project [27].

Map illustrating the full length of the Dakota Access Pipeline and its relation to Native American Reservations and shale gas formations. Image by Jasmine Cress, Tory Michak and Tatiana Nozaki

Completed in 2017, the DAPL is a 1,172 mile-long underground pipeline, roughly 30” in diameter, that transports crude oil from the Bakken Shale Oil formation in northwest North Dakota to a refinery in Petoka, southern Illinois. From its inception through its completion, peoples from the Standing Rock Sioux tribe, along with thousands of Native American supporters from across North America have fiercely protested against the construction of the pipeline. Fundamentally, the DAPL ignores the 1851 Treaty of Laramie, which remains the supreme law of the land, and determines that no developments can happen within the reservation without the consent of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe. Moreover, by traversing under Lake Oahe, just north of Standing Rock, the pipeline jeopardizes the primary water source for the reservation, along with Indigenous relationships to the land, water, and each other. Unceded seeks to reveal the social and environmental injustices inherent to the oft-hidden practices of colonial energy developments. The proposed interventions are intended to provoke thoughts, ideas, and actions—not to be misread as actual proposals. I will now briefly discuss three of nine total interventions proposed as part of this project.

Concrete, wax, and birch models of the nine interventions along the DAPL. Image by Jasmine Cress, Tory Michak and Tatiana Nozaki

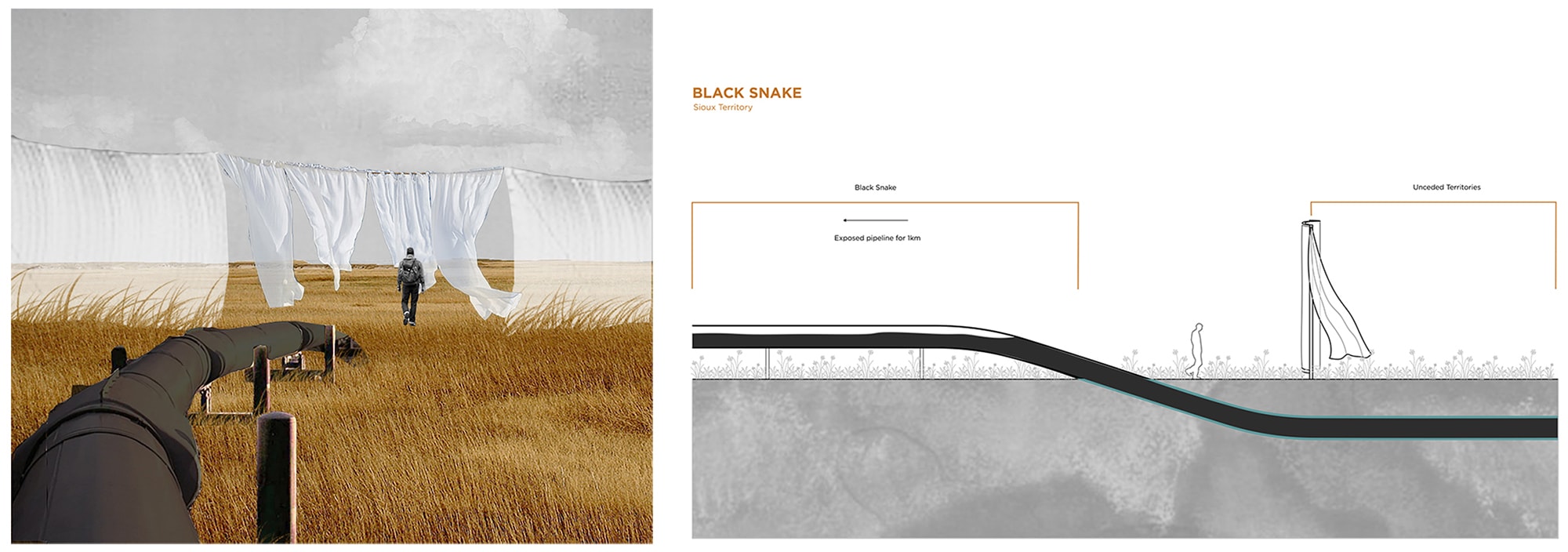

The Black Snake

The intervention The Black Snake marks the location where the pipeline crosses the unceded Sioux land, north of the Standing Rock Reservation. The notion of the Black Snake comes from the Lakota, who prophesied that “a great and evil black snake would someday descend and reap destruction, rendering their homeland uninhabitable to hunt and fish and their waters unsuitable for religious ceremony” [28]. This prophecy has tragically become a reality in the form of the DAPL. The intervention manifests itself as a curtain, marking the border between ceded and unceded territory. As the Black Snake moves into ceded (treaty-protected) territory, it visibly marks its presence on the land, willfully ignoring Indigenous treaty rights, sovereignty, and relations to the land.

Black Snake, entering the unceded territory of the Sioux Tribe. Image by Jasmine Cress, Tory Michak and Tatiana Nozaki

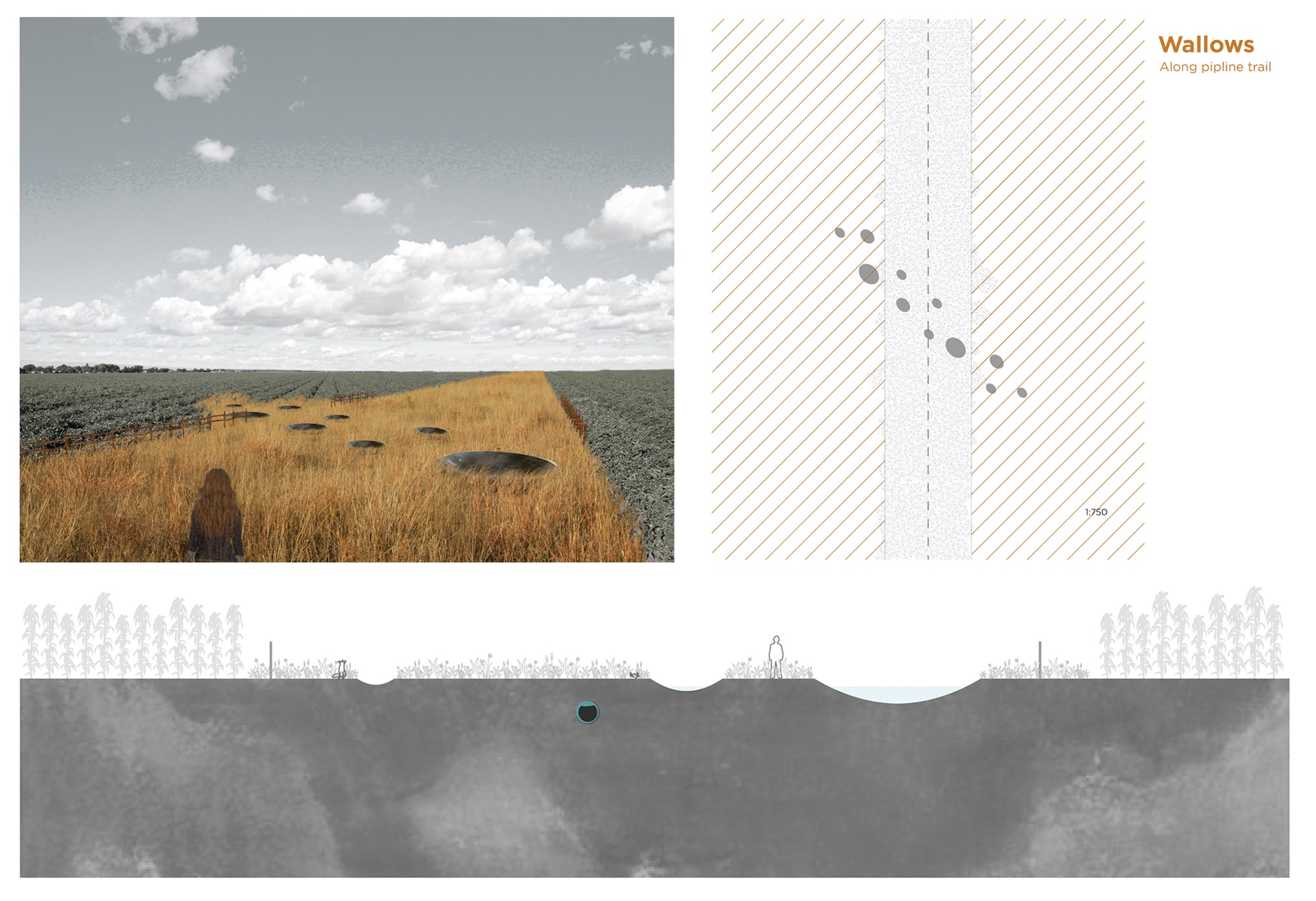

Wallows

Wallows commemorates Plains megafauna and the complex living systems and habitats sustained by them. Colonial settlement and the subsequent conversion of prairie grasslands into agriculture, combined with ongoing infrastructure developments (railways, highways, pipelines) have devastated and fragmented bison habitats. This intervention re-creates one of the iconic features of the Plains prairies: the wallows. These topographic depressions in the landscape were formed by thriving herds of bison while drinking, bathing, and rolling in naturally occurring shallow water holes for centuries. In locations marking historic bison migration routes, reflecting pools set in the ground hint at the historic presence of these animals. In addition, the entire pipeline easement is planted with native prairie grasses and flowers. The resulting thin band of prairie at once amplifies the presence of the pipeline while its contrast with adjacent monocultural agricultural crops signifies the cultural, spiritual, and environmental transformation of the Plains.

Wallows, shallow reflecting pools memorialize the enduring physical and spiritual presence of bison on the Plains. Image by Jasmine Cress, Tory Michak and Tatiana Nozaki

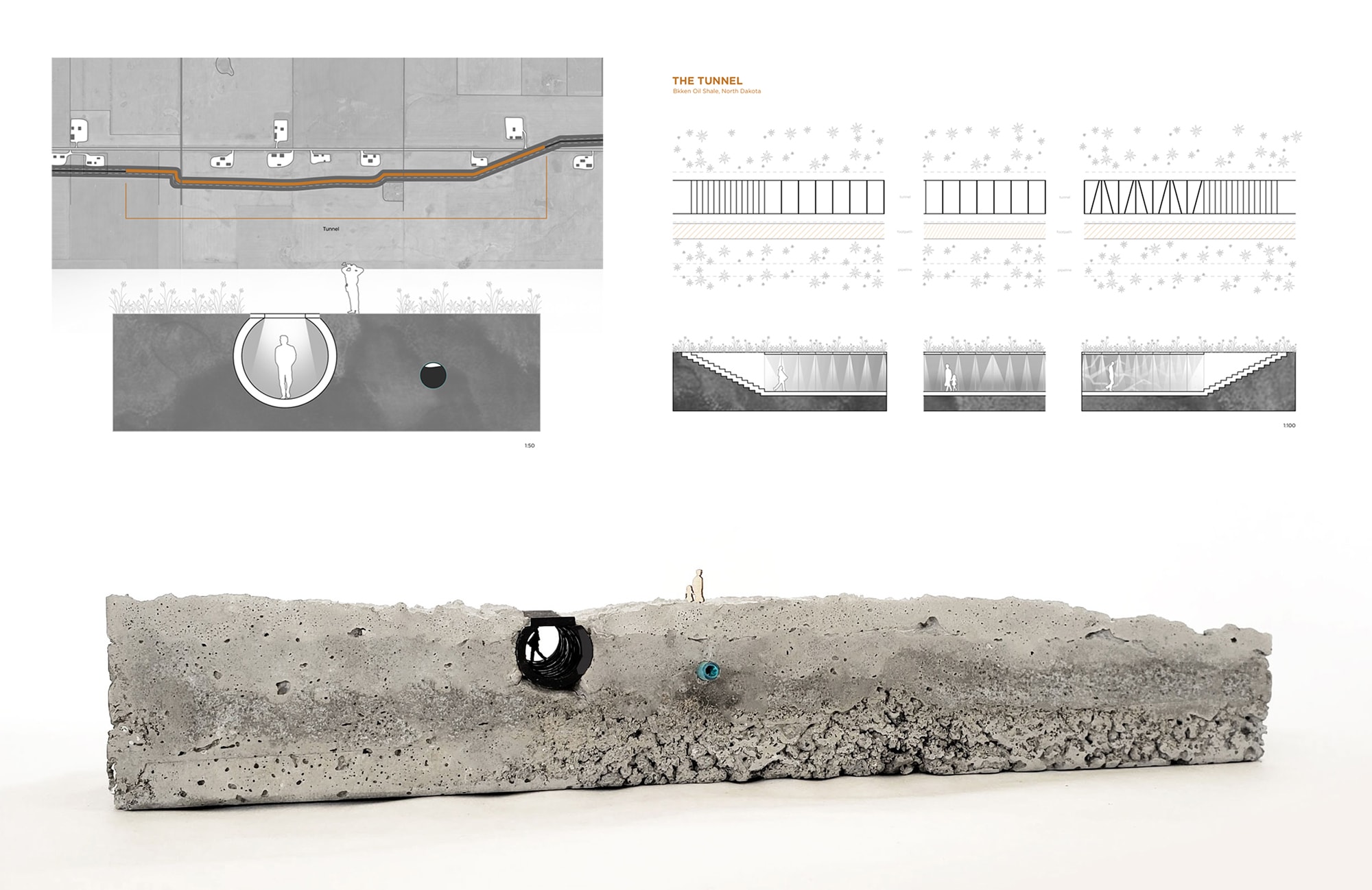

Tunnel

A final example is Tunnel, which uncovers the scale of underground fracking infrastructures and operations while creating a momentous embodied experience. The proposed tunnel, which runs parallel to the DAPL, has a length of 1.5 miles—the average depth of a vertical hydraulic fracking well. As visitors descend into the tunnel, they are confronted with the (in)visibility of the DAPL, as well as with the geological layers and timescales that are implied with the violent extraction of shale gas from the earth’s crust. Narrow slots in the ceiling allow for rays of light to penetrate the tunnel, creating a constant rhythm: light, dark, light, dark. The result is a mile-and-a-half-long procession through a space of terrible beauty, asking us to look inward and question our own values, beliefs, and relationship with nature and technology.

Tunnel creates a tension between the scale of underground fracking infrastructure and the embodied experience of terrible beauty. Image by Jasmine Cress, Tory Michak and Tatiana Nozaki

As illustrated by the examples above, the proposed interventions by Michak, Cress, and Nozaki, seek to navigate difficult and uneasy questions of design in the context of colonial energy infrastructure projects. Where contemporary design discourse too often overemphasizes material flows, environmental remediation, and engineered solutions, Unceded purposefully centers the discussion around the injustices to Indigenous peoples and more-than-humans implied by the ongoing devastation of energy developments.

Decolonization and Design

Decolonization demands designers to acknowledge the harm that is inflicted on Indigenous people, and subsequently, to act upon this knowledge. It also demands acknowledging treaty rights and addressing systemic inequalities, as well as critical engagement with Indigenous ways of knowing and making. This starts by examining our own values, and by questioning our relationships with the land, including the tendency of granting human ownership over non-human things and beings.

Instead, Indigenous botanist Robin Kimmerer encourages us to have a different relationship with the land:

“In the indigenous worldview, a healthy landscape is understood to be whole and generous enough to be able to sustain its partners. It engages land not as a machine but as a community of respected non-human persons to whom we humans have a responsibility…reconnecting people and the landscape is as essential as reestablishing proper hydrology or cleaning up contaminants. It is medicine for the earth” [29].

Especially for the discipline of landscape architecture, which fundamentally concerns investigations at the intersection of culture and the environment, discussions surrounding decolonization and alternative models of design and stewardship should be essential. Matthew Kiem suggests: “‘decolonizing design’ is not a ‘new’ or an additional form of design but a political project that takes design as such—including its theorization—as both an object and medium of action” [30]. This requires a critical examination of dominant conceptual frameworks, representational tools, and design strategies fostered within the discipline in order to ensure the landscape architects do not continue to perpetuate colonial practices.

In this context, climate adaptation must become a key vehicle for decolonization [31]. Due to ongoing challenges with respect to education, livelihood, remoteness, health, and reliance on ecosystem services, Indigenous communities and marginalized groups are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change [32]. Indigenous peoples have not been engaged in meaningful consultation, let alone in the co-design of alternative futures for their communities. Developing potential adaptation pathways to the climate crisis must be done in ways that fundamentally address the ongoing devastating consequences of colonization. This begins by respecting The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), which in addition to recognizing Indigenous peoples’ right to self-determination, states that “Indigenous peoples have the right to the lands, territories and resources which they have traditionally owned, occupied or otherwise used or acquired” [33].

Much can also be learned from Indigenous knowledge and social-ecological practices on the land-water interface. Indigenous knowledge about places, practices, and relations has been passed on through generations, evolved over time, and is based on a deep and nuanced understanding of human-nonhuman relationships. As the climate has always changed, albeit currently at faster rates, Indigenous communities have historically developed nuanced adaptation knowledge and practices. Far from static, these techniques and strategies have been tried and tested over the long-term, infused with continuous experimentation and innovation. As such, they provide important markers for an array of methods related to climate adaptation, including agroforestry, resource utilization, rainwater harvesting, and changing eating habits/diets, to name just a few [34]. Integration of this knowledge, and the worldviews that have produced these nuanced human-nature relationships, will be critical in order to overcome our reliance on hard engineering solutions and technological fixes.

In closing, this essay has aimed to foreground the legacies of colonial infrastructures and their ongoing impacts to the land and those who have shaped and inhabited it since time immemorial. Using the multifaceted lens of decolonization, I have offered some examples to illustrate potential ways designers can respond to these pressing challenges. While the approaches certainly have their shortcomings, most clearly lacking direct and sustained collaboration and interaction with the Indigenous communities implied in the proposals—as a collection, they begin to rethink the role of design in relation to notions of agency, sovereignty, relationality, and spatial justice. Bringing these discussions consistently to our classrooms and clients will help foster much-needed engagement with the histories, actualities, and futures of Indigenous territories. This begins by positioning ourselves, in the words of Zoe Todd: “within a broader and underlying awareness of, and tending to, the insistent and ongoing relationships formed among Indigenous peoples, lands, laws, and those of us who are guests within unceded and unsurrendered territories” [35].

Acknowledgments

I want to thank the thoughtful comments and feedback by the editors of this issue, which significantly improved the clarity of the essay. Additionally, I would like to thank and acknowledge all studio participants for participating in often difficulty but timely and conversations, as well as producing meaningful work that purposefully engaged design as a political project.

Studio Participants: Shaheed Karim, Lee Patola, Alex Scott, Benham Harper, Karen Tomkins, Sam McFaul. Weirong Li, Emily Soder-Duncan, Calvin Tan, Colin Jones, Tory Michak, Jasmine Cress, and Tatiana Nozaki.

Lastly, this work was produced at the University of British Columbia, which is located on the traditional, ancestral, and unceded territory of the xʷməθkwəy̓əm (Musqueam) people. The land it is situated on has always been a place of learning for the Musqueam people, who for millennia have passed on their culture, history, and traditions from one generation to the next on this site.

Kees Lokman is an assistant professor of landscape architecture at the University of British Columbia. His research focuses on design challenges related to sea level rise adaptation, water and food shortages, and the energy transition. Recent and ongoing research has been published in various journals, including the Journal of Landscape Architecture, Landscape Research, New Geographies, and the Journal of Architectural Education. This work has been funded through various agencies and municipalities, including Natural Resources Canada, the Dutch Creative Industries Fund, and the City of Vancouver. Kees is also the founder of Parallax Landscape, a collaborative design platform, which been recognized internationally and with numerous awards and mentions for contributing innovative design proposals.

Kees Lokman is an assistant professor of landscape architecture at the University of British Columbia. His research focuses on design challenges related to sea level rise adaptation, water and food shortages, and the energy transition. Recent and ongoing research has been published in various journals, including the Journal of Landscape Architecture, Landscape Research, New Geographies, and the Journal of Architectural Education. This work has been funded through various agencies and municipalities, including Natural Resources Canada, the Dutch Creative Industries Fund, and the City of Vancouver. Kees is also the founder of Parallax Landscape, a collaborative design platform, which been recognized internationally and with numerous awards and mentions for contributing innovative design proposals.

Notes

[1] Yazzie, K. Melanie and Baldy, Cutcha Risling. 2018. “Introduction: Indigenous peoples and the politics of water.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society Vol 7., No 1, pp. 1-18

[2] Tuck, E & Yang, K.W. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1(1), 1-40.

[3] Waziyatawin A.W., & Yellow Bird, M. (Eds.). (2005). For Indigenous eyes only: A decolonization handbook. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press.

[4] Yazzie, K. Melanie and Baldy, Cutcha Risling. 2018. “Introduction: Indigenous peoples and the politics of water.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society Vol 7., No 1, pp. 1-18

[5] Ibid.

[6] Todd, Zoe. 2016. “From Classroom to River’s Edge: Tending to Reciprocal Duties Beyond the Academy.” Aboriginal Policy Studies 6 (1).

[7] Bélanger, Pierre. 2018. “The Decolonization of Design.” Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation. https://www.arch.columbia.edu/events/824-the-decolonization-of-design-pierre-belanger

[8] Capossela, Peter. 2015. “Impacts of the Army Corps of Engineers’ Pick-Sloan Program on the Indian Tribes of the Missouri River Basin.” Journal of Environmental Law and Litigation 30 (1), pp. 143-218.

[9] Yazzie, K. Melanie and Baldy, Cutcha Risling. 2018. “Introduction: Indigenous peoples and the politics of water.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society Vol 7., No 1, pp. 1-18

[10] Committee on Missouri River Ecosystem Science, National Research Council, Division on Earth and Life Studies Staff, Water Science and Technology Board Staff, National Research Council (U.S.). 2002. The Missouri River Ecosystem: Exploring the Prospects for Recovery. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press.

[11] Schneiders, Robert Kelley. 1997. “Flooding the Missouri Valley: The Politics of Dam Site Selection and Design.” Great Plains Quarterly 17 (3/4): 237-249.

[12] Griffith, Jane. 2018. “Do some work for me: Settler colonialism, professional communication, and representations of Indigenous water,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, Vol 7., No 1, pp.132-157

[13] Philip P. Frickey, Domesticating Federal Indian Law, 81 MINN. L. REV. 31, 83, n.206 (1996).

[14] Todd, Zoe. 2016. “From Classroom to River’s Edge: Tending to Reciprocal Duties Beyond the Academy.” Aboriginal Policy Studies 6 (1).

[15] Davidson, John H. 1999. “Indian Water Rights, the Missouri River, and the Administrative Process: What are the Questions?” American Indian Law Review 24 (1): 1-20.

[16] Nebraska v. Wyoming, 325 U.S. 589 (1945), 618.

[17] Davidson, John H. 1999. “Indian Water Rights, the Missouri River, and the Administrative Process: What are the Questions?” American Indian Law Review 24 (1): 1-20.

[18] Davidson, John H. 1999. “Indian Water Rights, the Missouri River, and the Administrative Process: What are the Questions?” American Indian Law Review 24 (1): 1-20.

[19] U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Omaha District. Missouri River Recovery Management Plan – Climate Change Assessment (Draft). December 2016. https://cdm16021.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/api/collection/p16021coll7/id/3063/download

[20] Mali Sélingué. “Declaration of Nyéléni.” 27 February 2007. Available online: http://nyeleni.org/spip.php?article290

[21] Salmón, Enrique. 2012. Eating the Landscape: American Indian Stories of Food, Identity, and Resilience. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

[22] Soder-Duncan, Emily, Karen Tomkins. 2019. “Sovereign-Pte” Sitelines, April 2019, pp. 7-8. http://www.sitelines.org/sites/default/files/sitelines_issues/Sitelines_April2019_web_0.pdf

[23] ibid.

[24] ibid.

[25] Zontek, Ken. 2007. Buffalo Nation: American Indian Efforts to Restore the Bison. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

[26] Coté, Charlotte. 2016. ““Indigenizing” Food Sovereignty. Revitalizing Indigenous Food Practices and Ecological Knowledges in Canada and the United States.” Humanities 5 (3)

[27] Cress, Jasmine, Tory Michak, and Tatiana Nozaki. 2019. “Unceded” Sitelines, April 2019, pp. 5-6. http://www.sitelines.org/sites/default/files/sitelines_issues/Sitelines_April2019_web_0.pdf

[28] Rome, Andrew. 2018. “Black Snake on the Periphery: The Dakota Access Pipeline and Tribal Jurisdictional Sovereignty.” North Dakota Law Review 93 (1): 57.

[29] Kimmerer, Robin Wall. 2013. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants. First ed. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Milkweed Editions.

[30] Schultz, Tristan, Danah Abdulla, Ahmed Ansari, Ece Canlı, Mahmoud Keshavarz, Matthew Kiem, Martins, Luiza Prado de O, et al. 2018. “What is at Stake with Decolonizing Design? A Roundtable.” Design and Culture 10 (1): 81-101.

[31] Howitt, R., Havnen, O. & Veland, S. Natural and unnatural disasters: responding with respect for indigenous rights and knowledges. Geographical Research 50, 47–59 (2012).

[32] Green, D., Jackson, S. and Morrison, J. (eds), 2009: Risks from Climate Change to Indigenous Communities in the Tropical North of Australia. Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency, Canberra.

[33] UN General Assembly. United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, resolution / adopted by the General Assembly, 2 October 2007, A/RES/61/295, available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/471355a82.html

[34] Makondo, Cuthbert Casey and David S. G. Thomas. 2018. “Climate Change Adaptation: Linking Indigenous Knowledge with Western Science for Effective Adaptation.” Environmental Science and Policy 88: 83-91.

[35] Todd, Zoe. 2016. “From Classroom to River’s Edge: Tending to Reciprocal Duties Beyond the Academy.” Aborigial Policy Studies 6 (1).

Cite

Kees Lokman, “The Missouri River Basin: Water, Power, Decolonization, and Design,” Scenario Journal 07: Power, December 2019, https://scenariojournal.com/article/Missouri-River-Basin/.