urban [ˈɜːbən] adj

1. (Social Science / Geography) of, relating to, or constituting a city or town.

2. (Social Science / Geography) living in a city or town.

forest [ˈfɒrɪst] n

1. (Forestry) a large wooded area having a thick growth of trees and plants.

2. (Law) An area of woodland, especially one owned by the sovereign and set apart as a hunting ground with its own laws and officers.

In the last decade, contemporary urbanism has undergone a radical change in its conceptualization and description of the urban landscape and its relationship to its surroundings. The emergence of the mega-urban landscape has led even the most rational voices in urbanism to become tethered to a discourse of sustainability. Within this paradigm, the urban forest has become both a troupe and a programmatic stalwart – acting as a largely symbolic gesture serving to legitimize the production of cities through the notion of a “green” urbanism.

On its own, the “urban forest” seems self-explanatory and banal, characterized largely by spatial proximity and contrasting territories and functions. However, in addition to its literal definition – a forest within or adjacent to the city – the urban forest can also be understood in the context of hybrid progressions, wherein it serves as a rhetorical device that challenges the idea of the classical urban core and questions the possibility of a new form and pattern of urban expansion. In this sense, the urban forest highlights the potential for forested land to serve as a meaningful urban typology capable of promoting a topographic and ecological evolution in a mega-urban landscape.

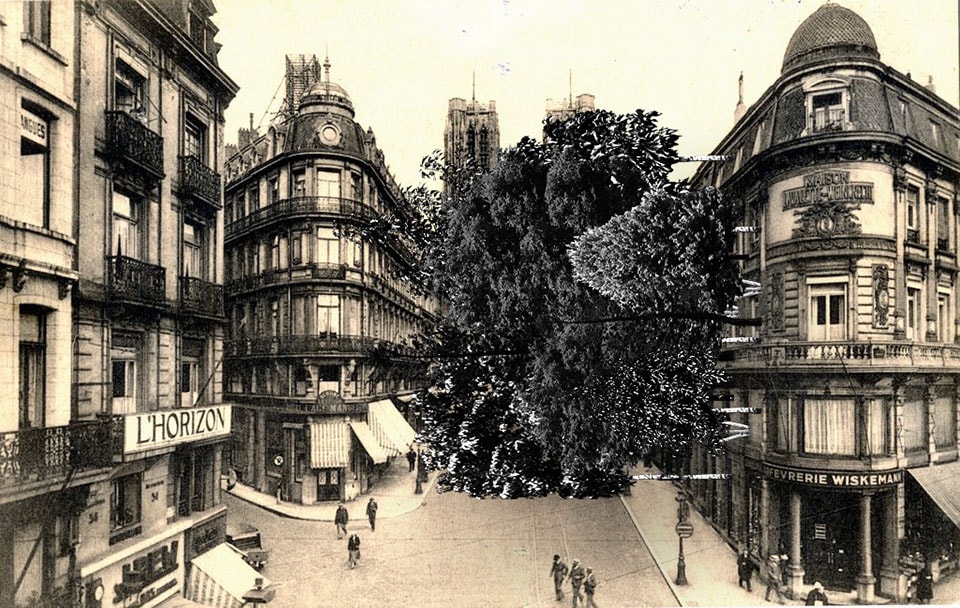

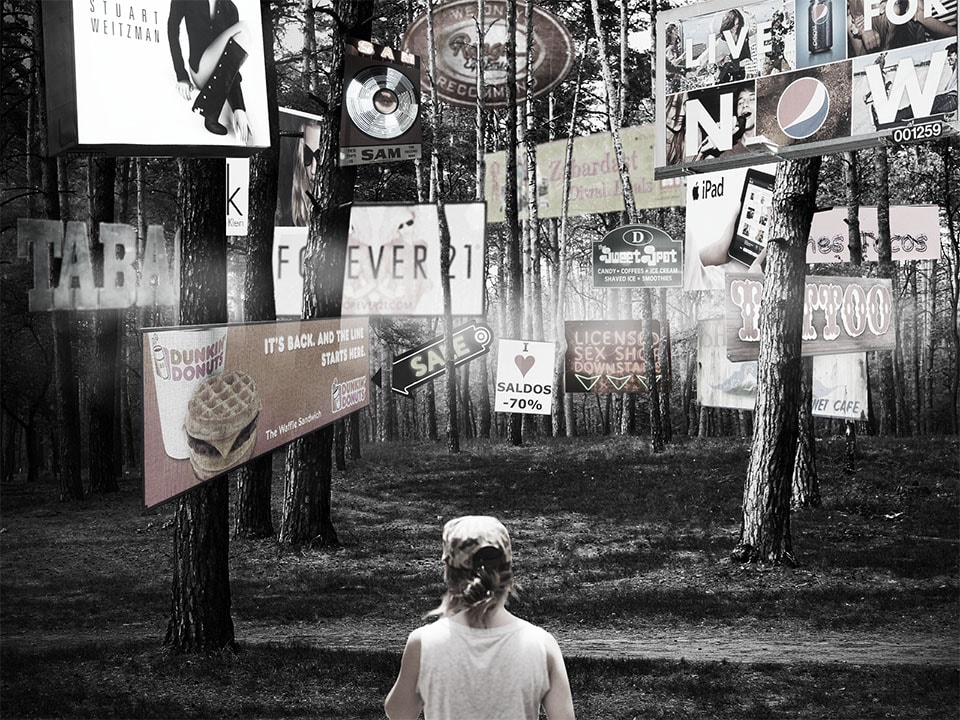

Romanticized binaries: the urban person in the forest is the same as wild animal in the city

Romanticized binaries: the urban person in the forest is the same as wild animal in the city

As the title of this issue (Scenario 4: Building the Urban Forest) suggests, there is a possibility of constructing a new paradigm of landscape urbanism today, one which does away with the paradoxical and unhelpful binaries of urban versus forest, of nature versus nurture, but instead promotes a synthetic project by exploring the productive possibilities of fusing together urban and forest. It’s a proposition to recognize the significance and instrumentality of forests as ecologically complex, spatially layered and dynamic systems that contribute to contemporary urban production. It suggests that the forest can, and does grow within human settlements; forming novel ecosystems that fuse wilderness and metropolis; a sophisticated natural system that could be managed and sustained within the city. Perhaps, as forests are considered through the lens of urban ecology, we might recognize the ways in which they benefit citizens and add value to cities – by mediating water, clean air, sunlight, shade, shelter to animals, and local climate. Ultimately, the urban forest is a place for citizens to escape the city and it’ll be an inexorable rebellion…

The urban forest is a mixture of two archetypes brought together to create an entirely new condition. However, creating such a synthesis simply through a superficial combination of heterogeneous archetypes and features can only result in a problematic and sloppy synthesis. Therefore, the following collages question the expedient definition of urban forest as a total environmental and urban system by stressing the fundamental differences between these two ideas. The drawings examine a paradoxical inversion of these archetypes, in which the city and the forest are each articulated through their contextual nature, and when merged together, maintain traces of their problematic encounter while also denouncing their incapability to function as a synthetic whole.

In order for the urban forest to have social meaning, it must be legible as a form and as a system – revealing the workings of each entity through their juxtaposition. The justification of these archetypes does not rely solely on their conjunct symbolism, meaning and quality, but builds off each idea to stand individually and create something new through a productive tension.

Tender junction: The city and the forest can never be brought together. They either oppose to each other or take over one another. It is in-between… It cannot serve as none of them. It is a dead city and a ruined forest, it is post-apocalyptical place where neither a human nor an animal can exist as it used to before, it is forced to learn to survive again.

City Decoration: The forest in the city can be considered as green facade: plants are constrained to grow on the vertical surface being victims of the fashion for the nature. They are just a decoration without its initial features and abilities. Same is the forest which by the whim becomes a decoration for the city.

Cliché: It was nature through the lens of the city. It was as the city itself created by the society for society and the forest in the city can never be the real forest as it will be created by the very same principle.

Masquerade of the City: The forest caged in the city is swallowed by it, digested. It can never remain the same. It has to live by the rules set in the city, it has to survive and adapt. It has to wear masks that are for the city embedded faces. It has to hide, it has to suffer. It is colonized.

Anna Misharina completed a Bachelor degree in architecture from the Moscow Architectural Institute and graduated with a Master degree in architecture from the Umea School of Architecture in Umea, Sweden.

Anna Misharina completed a Bachelor degree in architecture from the Moscow Architectural Institute and graduated with a Master degree in architecture from the Umea School of Architecture in Umea, Sweden.

Keith Chung completed a Bachelor degree in architecture from the Boston Architectural College and graduated with a Post-Master degree in architecture from the Berlage in Delft, Netherlands.

Keith Chung completed a Bachelor degree in architecture from the Boston Architectural College and graduated with a Post-Master degree in architecture from the Berlage in Delft, Netherlands.

Keith and Anna are the co-founders of studio CRIT, a research studio that stresses the capacity of architecture as a multi-disciplinary practice with writing, research and design intervention. The studio focuses on understanding spatial conceptualization and production in relation to the changing context of both increasing globalization and the dispersal of local cultures.