“The conservation idea covers a wider range than the field of natural resources alone. Conservation means the greatest good to the greatest number for the longest time…It proclaims the right and duty of the people to act for the benefit of the people. Conservation demands the application of common-sense to the common problems for the common good.”

– Gifford Pinchot, The Fight for Conservation, 1910

“The Third Landscape can be considered as the genetic reservoir of the planet, the space of the future.”

– Gilles Clément, The Third Landscape, 2003 [1]

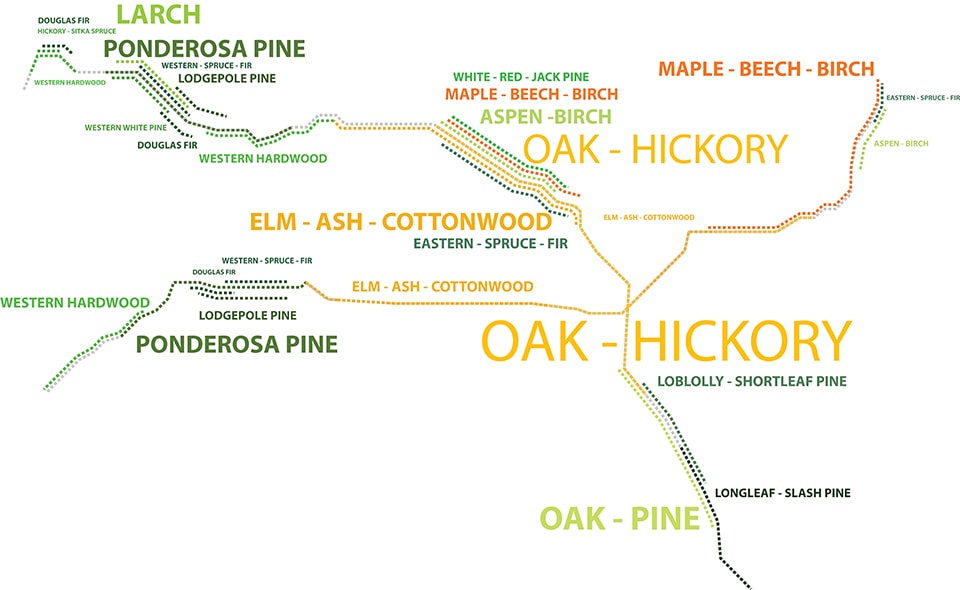

In America, the forests of our past stretched across the continent, in wide bands, with distinct species marking the different longitudes and latitudes of the vast territory. Surveyors had to devise new systems of measurement to address the wooded landscape—the European precedent only worked for a denuded terrain with vast open views. The American forest was dense and occluded, unmatched in its richness and diversity. The famed naturalist John Muir described them as the best that God ever planted [2]. The transect was impressive from the eastern spruce-fir and the beech-maple-birch forests of the northeast to the loblolly pinelands of the southeast through oak forests and aspen-birch tracts, to the dry ponderosa pines and the deciduous conifer larches onward to the immense western hardwood forests and the coastal lands of Douglas fir, Sitka spruce and redwoods.

Diagram of United States Forest Types

These trees, as decried by Muir, gave way to urban progress with its agricultural fields, cityscapes, infrastructural projects and industry. But as the cycles dictate, the forests are re-emerging, as spontaneous woodlands on abandoned farms, foreclosed subdivisions, vacant parcels, un-mown right-of-ways and former factory sites. As landscape architect Gilles Clément indicates, these are the forests of the future, the sites to be targeted, re-invented and claimed as the next commons.

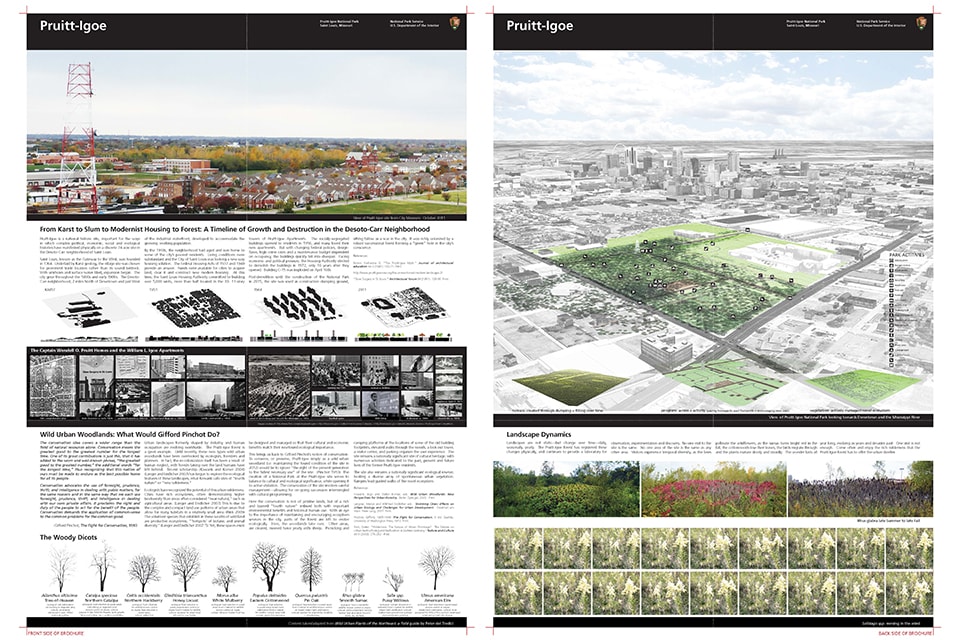

Aerial View of Pruitt Igoe Woodlands taken from the City Museum

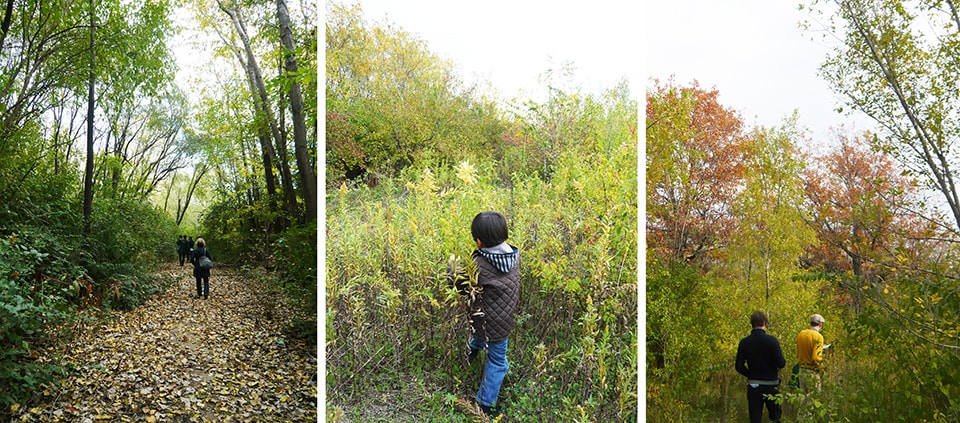

One such tract—a 33-acre parcel—sits less than one mile from downtown Saint Louis. The site is stunning, both from a distance and on the ground. To penetrate the overgrown perimeter (the fence is a key element in the ecological toolbox, collecting seeds, protecting seedlings and fostering incredible spontaneous plant growth), is to discover a magical interior. Trees loom over forgotten streets with occasional street lamps and manhole covers signaling former development. Rolling topography, formed from the dumping of construction waste, supports varied vegetal communities—a testament to the idea that complex, urban land use patterns yield high biodiversity [3]. Perfect sumac domes have found their ideal home and the site has attracted a suite of species capable of both thriving in the harsh environment and contributing ecosystem and aesthetic benefit.

Rich Spontaneous Vegetation Covers the Site

The place is remarkable both for its present constitution and past legacy. Once the home of the infamous modernist public housing project—the Captain Wendell O. Pruitt Homes and the William L. Igoe Apartments—the contested site has remained in limbo since their demolition, long enough to grow into a substantial wild urban woodland [4]. Yet, after forty years, the tower demolition imagery remains the most well-known and proliferated symbol of the site [5], while the burgeoning forest is unrecognized, overlooked as a resource worth mentioning, much less celebrating or conserving.

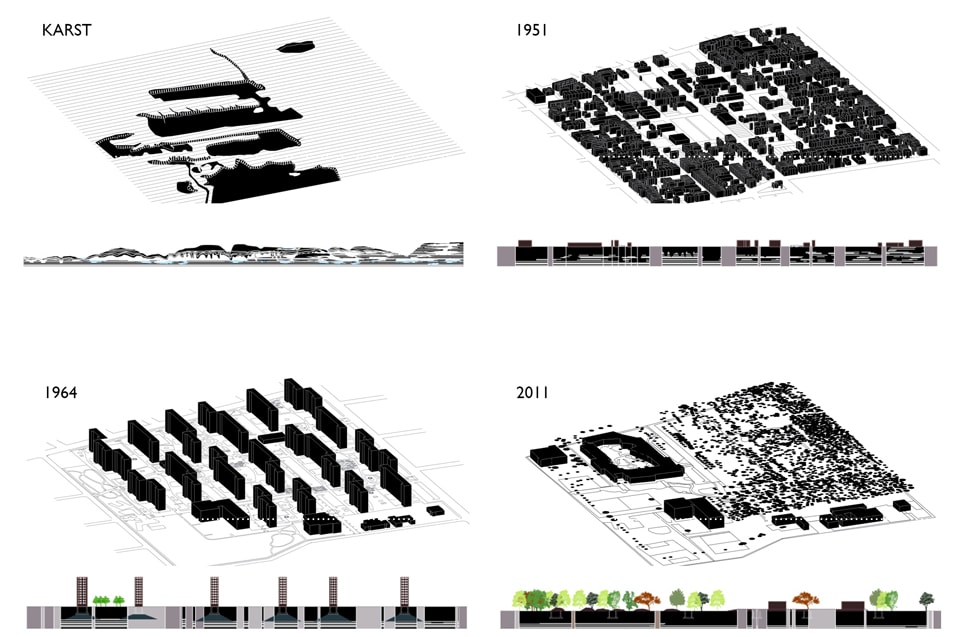

Saint Louis, the Gateway to the West, was founded in 1764. Underlaid by Karst geology, the village site was chosen for its prominent trade location rather than its sound bedrock. With sink holes and surface water filled, expansion began. The city grew throughout the 1800s and early 1900s. The Desoto-Carr neighborhood, located 2 miles north of downtown and just west of the industrial waterfront, developed to accommodate the growing working population. By the 1930s, the neighborhood had aged and was home to some of the city’s poorest residents. Living conditions were substandard and the City of Saint Louis was looking for a housing solution. The Federal Housing Acts of 1937 and 1949 provide an answer. Funds were available for cities to acquire land, clear it and construct new modern housing. Saint Louis led the nation in the envisioning, planning and construction of these towers—deemed a welcome sanitary alternative to the previous condition.

The Saint Louis Housing Authority committed to building over 5,000 units, more than half located in the 33- 11 story towers of Pruitt-Igoe. The racially-segregated buildings opened to residents in 1956, and many loved their new apartments. But with changing federal policies, design-flaws, high crime rates and a maintenance budget dependent on occupancy, the buildings quickly fell into disrepair. Facing economic and political pressure, the Housing Authority elected to demolish the buildings in 1972, only 18 years after it opened.

Post-demolition, the site sat unused, with high levels of debt and social stigma discouraging development but welcoming floral and faunal invaders. It was used as a construction dumping ground, taking much of the material from the stadiums and the convention center, but otherwise sitting fallow as a scar in the city. In the early 1990s, 57 acres were given to the construction of the Gateway school complex. The site was capped, with a large berm burying the toxins below. The remaining 33 acres continue to be richly colonized by a robust successional forest forming a “green hole” in the city’s conscience.

Diagrams Showing Major Site Transformations from Karst Geology through Development Cycles to Wild Urban Woodland

The unique circumstances surrounding the Pruitt-Igoe site have protected it from development, especially the often seen transition from modernist public housing towers to HOPE VI style suburban enclave. This transformation can be seen on the adjacent site. However, after forty years, the pressure seems more imminent. A local suburban developer, Paul McKee, known for his corporate campuses on greenfield sites, has targeted the neighborhood for his next project, Northside Regeneration. He has purchased over 2,220 parcels in the surrounding neighborhoods, including an option on the Pruitt-Igoe site [6]. The project has garnered political support but the vision remains nebulous. There is no question that the area is in need, as one of the hardest hit areas of population and economic loss, and McKee’s emphasis has been on job creation. Yet, he is treating the land as vacant, as a brownfield tabula rasa akin to his greenfield sites, disregarding past use, and present occupation. It is true that many have left the neighborhood, but those who have remained have chosen to do so. Any future development should respect the resilient, both the human and the floral and faunal.

In Detroit, by contrast, the urban forest is becoming an alternative development model for the extensive, yet perforated, open land. Local planners champion a 140-acre project advertised as a reforestation initiative [7]. John Hantz, a local financier, has obtained a series of non-contiguous parcels on the east side of the city. His proposal, dubbed the Hantz Woodlands, is for the planting of 15,000 trees. The project is unabashedly an economic one, designed for profit through tree harvesting. Much like the Northside Regeneration project in Saint Louis, the details have yet to surface, but Hantz vows for the sites to be open to the public, without fences, allowing free passage among the trees. The implication is a hybrid, civic-economic forest, an alternative urban infill scheme. The idea of a forest running through a city is not a new one—but the idea of a managed, productive urban forest is intriguing and untested. The Hantz project, however, despite self-proclamation, is not an urban forest. Instead, it is more akin to a large scale nursery demonstration. The ornamental planting seems out of place amid the extensive urban wilds. The plots of volunteer vegetation found across the city which is slowly moving into an early successional forest (as evidenced by the Pruitt-Igoe site) have greater potential to seed the next urban forests. The Hantz proposal actively intervenes, by planting woodlands as if they were gardens, when embracing and managing the emergent woodlands is likely a better alternative in a resource-strapped environment.

A small stand of trees is being planted in Detroit while another is being eradicated in Saint Louis. The Northside Regeneration project in Saint Louis seeks to remove the successional forest on the Pruitt-Igoe site, a landscape forty years in the making [8]. Perhaps the argument is that Saint Louis already has a Forest Park – a much-loved and well-frequented park that belies its name. There are countless Forest Parks in the United States, many developed during periods of industrialization as ways to escape the evils of urban life. Some of these parks, like the 5,100 acre woodland in Portland, Oregon remain true to their name whereas others, and Saint Louis’s fits in this category, are forest parks largely in name only. In Saint Louis, a corner of the 1,371 acre park remains treed, while the rest is heavily programmed with recreational activities. Overall, the site has an average of only thirteen trees per acre. While it hosts a primary forest, a secondary successional forest, and several fragile ecosystems, the park is best known for its cultural amenities including a free zoo and a museum housed in Cass Gilbert’s World’s Fair Exposition Palace of Fine Arts building. So while the name is taken, there is still room for a second forest park in Saint Louis. This second generation Forest Park has the ability to capitalize on the urban successional woodlands as a resource capable of providing ecosystem value—carbon sequestration, heat island reduction, stormwater mitigation, biodiversity—while anchoring neighborhood transformation and development.

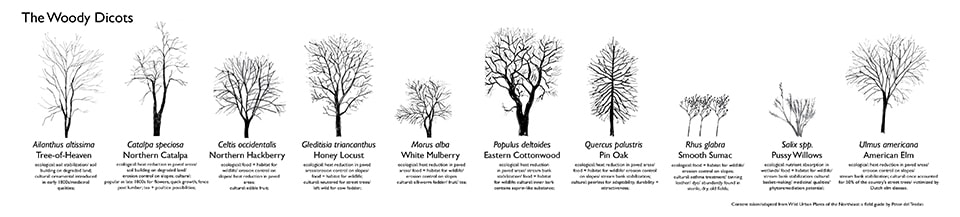

Ecologists have recognized the potential of the wild urban woodlands. Cities have rich ecosystems, often demonstrating higher biodiversity than areas often considered “near-natural,” such as agricultural areas [9]. This is due to the complex and compact land use patterns of urban areas that allow for many habitats in a relatively small area [10]. The volunteer species that establish in these swaths of woodland are productive ecosystems, “‘hotspots’ of botanic and animal diversity.” [11] These spaces of newfound environmental significance—dubbed novel ecosystems [12] —are the contribution of the anthropocene. The forests of our future are hybrid spaces, rich and layered biomes shaped directly and indirectly by human activity. Their design and management must address ecological, as well as cultural and economic requirements. It is time for urban designers to join their ecological cohort in championing the successional urban forest as an important element in urban restructuring. The insertion builds on past landscape infrastructures, large tracts of land like the Forest Parks or the 1,100 acre Emerald Necklace in Boston, set aside as civic amenities. It recognizes both the need to adopt former sites of human occupation as the next fodder for conservation and the impetus to restore balance to the urban environment. The successional urban forest recycles land and provides breathing room in formerly dense conurbations with species well-adapted to the given conditions.

Key Wild Urban Woodland Species Found on Site

The tools of design are twofold: one at the regional or city-wide scale and one at the site level. The existing and potential forested tracts must be identified, drawn and configured to form the backbone of future development. They must be set aside, acquired much in the same way early conservation pushed the creation of America’s National Parks. The decision as to what to un-build is as fundamental as what to build. Conserved forests may become one element in a larger citywide development strategy that addresses the full complexity of issues facing cities losing population. Then, at the site scale, the forests require greater interpretation. They cannot be simply conserved as ecological preserves or held to an idealized pre-human nature, which National Parks at times foolishly attempt. The latter is counter to the very definition of the novel ecosystem while the former would ignore Gifford Pinchot’s key notion of conservation. To conserve, or preserve, Pruitt-Igoe and analogous sites simply as a wild urban woodlands would be to ignore “the right of the present generation to the fullest necessary use” of the sites themselves [13]. Instead, the woodland conservation demands careful management—allowing for on-going succession intermingled with cultural programming.

The Site as a National Park

Speculative Program Distribution

Designed experimental landscapes afford the chance to vary the extent of intervention, with some areas left to continue unabated growth, others arrested in states of incomplete succession and still others design for active human use [14]. The strategies evoke those used in early American parks, with sheep grazing and visitors ambling, but the presentation is direct, with a contemporary view of the ecological and cultural landscape as slowly evolving, dynamic space meant to reconcile past occupation with present demands. Resources are limited and they must be understood, respected, conserved, and adapted rather than wiped clean for the next wave of short-sighted subdivisions. The nascent forests emerge from the overgrown vines and scrubby trees. Inside there is enchantment awaiting discovery.

Jill Desimini is an Assistant Professor of Landscape Architecture at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design. Prior to joining the full-time faculty, she was a Senior Associate at Stoss Landscape Urbanism in Boston. She holds master of landscape architecture and master of architecture degrees from the University of Pennsylvania and a bachelor of arts in urban studies from Brown University. Her research focuses on reproductive strategies for abandoned urban lands.

Jill Desimini is an Assistant Professor of Landscape Architecture at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design. Prior to joining the full-time faculty, she was a Senior Associate at Stoss Landscape Urbanism in Boston. She holds master of landscape architecture and master of architecture degrees from the University of Pennsylvania and a bachelor of arts in urban studies from Brown University. Her research focuses on reproductive strategies for abandoned urban lands.

Notes: