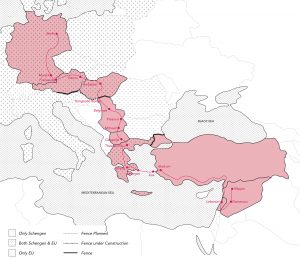

The Syrian Civil War is the deadliest conflict of this century. Since the conflict began in 2011, 12.5 million Syrians have been displaced from their homes, nearly 60% of the total population, the largest exodus of a population from their home country ever witnessed [1]. Additionally, nearly 5 million refugees have fled Syria, seeking safety in Lebanon, Turkey, Jordan, and beyond [2]. This mass migration has affected regional and global politics, economics and culture. Migration also fuels spatial transformation. In the absence of coordinated response and intervention, the flow of refugees into neighboring countries such as Lebanon has swiftly restructured the landscape through millions of individual acts of intervention and settlement. As migrants seek to make a home in a landscape of displacement, they often occupy leftover territories, land that has itself been passed over or discarded.

This paper reports on the research of the Landscape in Emergency Research Group and its explorations of the role of landscape design on the landscapes of displacement caused by the Syrian crisis in Lebanon. It explores the importance of the interaction and communication between design experts and community members in envisioning scenarios of intervention to address the adversity created by displacement and temporary settlement.

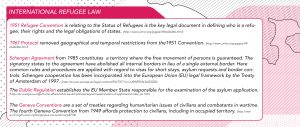

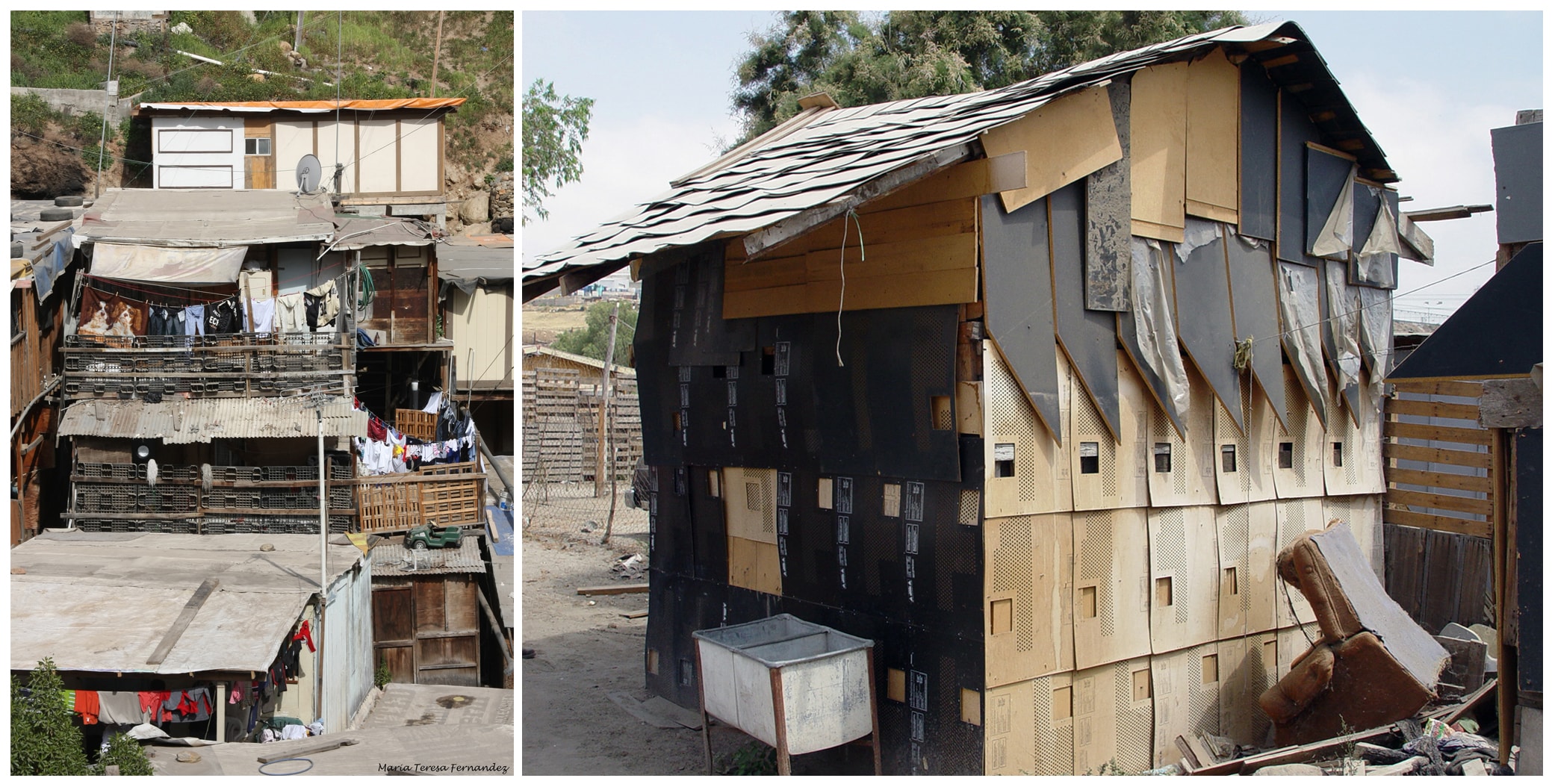

Informal Settlement’s condition in Lebanon. Photo by Maria Gabriella Trovato.

Syrian Crisis in Lebanon

Lebanon is host to nearly 1.2 million Syrian refugees, representing around a quarter of the country’s total population. Since the Syrian Civil War began, refugees fleeing the conflict have settled in every corner of Lebanon, putting a significant strain on already stretched services and infrastructure [3].

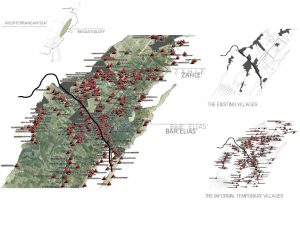

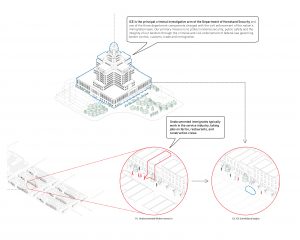

Presently, roughly 42,000 illegal tents are scattered across the country in approximately 1,500 locations throughout Lebanon mainly concentrated in the North and in the Bekaa Valley. Lebanon represents a unique condition, as it is the only country in the region neighboring Syria that has refused to allow for the establishment of formal camps despite offers of assistance from the United Nations High Commission on Refugees’ (UNHCR). Thus, the UNHCR shelter group was and is still not able to neither suggest nor change the location of the dispersed Informal Tents Settlements throughout Lebanon. Their distribution in the Lebanese regions depends on family and religious affiliations, and it is also under the control of individuals known as ‘Shawish’, who initiate connections between Syrians refugees, in search of location, and Lebanese owners, ready to reorganize their land to accommodate informal shelters and rent them to the new comers. The majority of the Syrian Informal Settlements (ISs) are located in agricultural fields which, under the pressure of the mass migration, were illegally changed in use and converted by their owners in ISs without respecting the minimum standard requisites stated in the ‘Handbook for Emergencies’ (UNHCR, 2007). Their dimension vary from one place to another and could range from a really small settlement, with less than ten families, to the largest that settles up to 100 families.

In the wake of the Syrian crisis, about 42,000 illegal tents are scattered at nearly 1,500 locations throughout Lebanon, mainly concentrated in the north and Bekka Valley. Image by Maria Gabriella Trovato.

This approach to building Informal Tent Settlements (ITS) all too often disregards the knowledge, culture and identity of both local and refugee populations. While this approach has allowed for the efficient construction of hundreds of ITS, it has also led to the segregation and alienation of Syrian communities, and the creation of slums and shantytowns.

These conditions are particularly damaging to populations displaced by disaster and civil war where communities and families have been torn apart and lost a great deal of their autonomy. In the ITS, individuals are forced to live together, day by day, and share restricted areas without knowing each other. They typically have no freedom to choose neighborhood, quality or typology of space.

Furthermore, while not planned and not inserted in a strategic vision, all of these ITS, enclosed entity without connection to the urban structure, are threatening the already compromised ecological, social, and cultural stability of the country. At environmental level the dispersion of the cluster of tents throughout the productive land, and their location near by water infrastructures, are boosting the degradation of the fertile soil and doubling the elevated percentage of water, soil and air pollution.

Al Tyliani

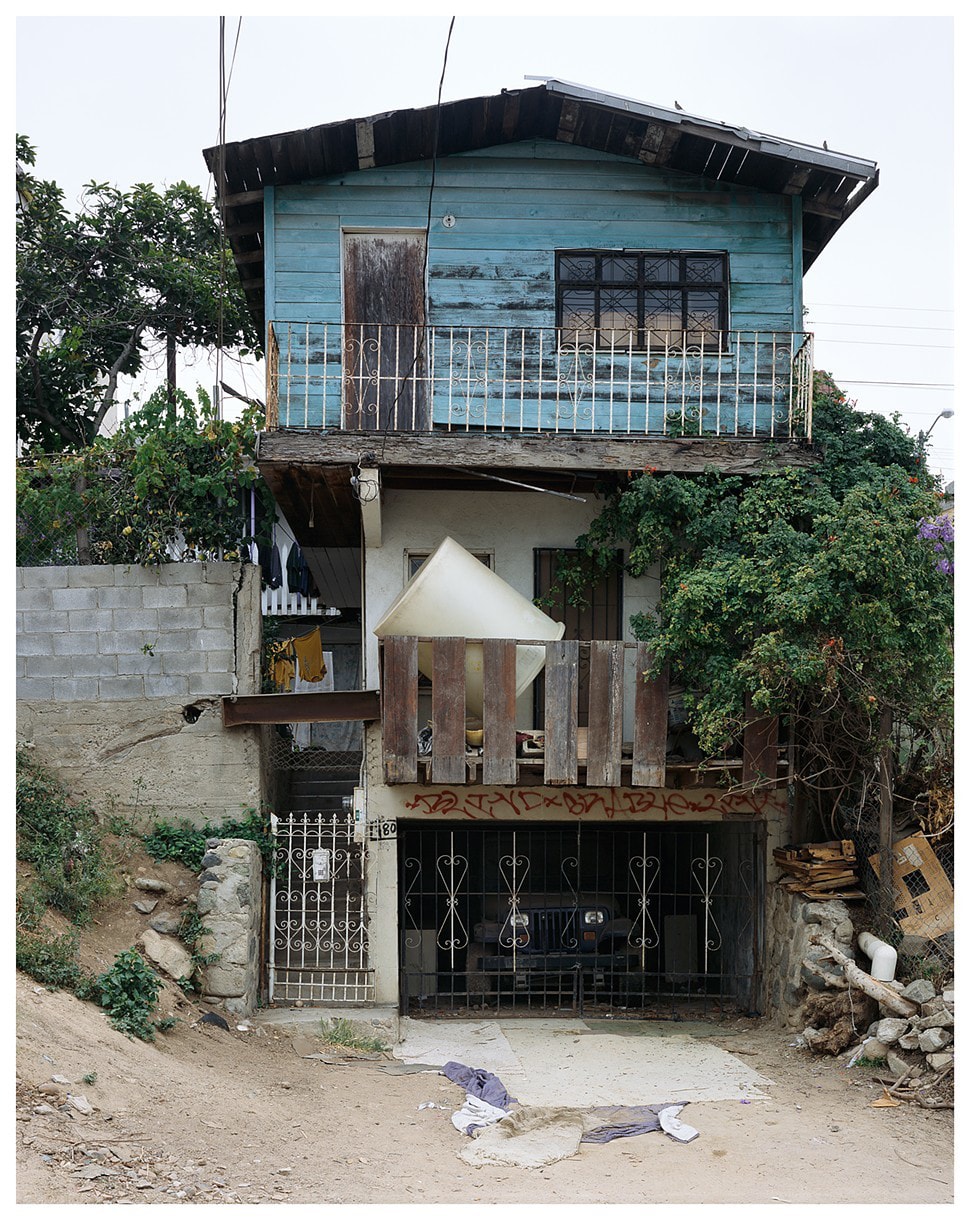

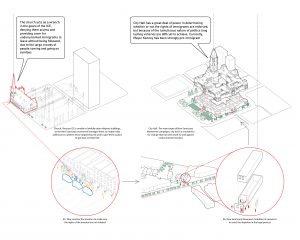

Al Tyliani ITS in Bar Elias, Bekaa Governorate took its name from Mr. Mosaab Al Tyliani the owner of what used to be a small agricultural field growing lettuce and potatoes. In 2011 the owner covered its land with concrete slabs converting the productive field to an informal settlement to accommodate the tents. In doing so, he compacted the soil, shaped three main roads and built five strips of concrete ready to house the 60 shelters. The newly produced landscape is the result of a new type of investment on the land that the landlord undertook. In order to control the expansion, the landowner overlaid a grid of vehicular roads to the ground, separating rows of a maximum of 10 tents sized 4 meters by 8 meters.

This planned grid was not strictly followed during construction; some tents are bigger or smaller than the mandated size, some protrude into pathways and occupy communal space. The resulting configuration generated a diversity of conditions between the tents which were used in some cases as alleys, in other ones as private or semi private spaces, as ornamental or kitchen gardens or as neglected left-over spaces. However, for the last six years, this 9000 square meter parcel has hosted 63 tents, providing a home to 66 families and around 440 people.

Extension of the private space of tent versus the open areas of the ITS. Photo by Maria Gabriella Trovato.

Once the ITS was laid out, the refugees used basic material to built their shelters. The view from above reveals a monochromatic and monotonous sequence of informal structures, with tents situated in neat rows, like a military campsite. However, the view from the ground reveals a complex blurring of material and immaterial boundaries, with ambiguous identities, ownership and hierarchy of spaces (public, collective, semi-private, private). Over time, the initial configuration of the tents has transformed as occupants added new rooms, internal courts and small gardens. The profile and figure of tents have further transformed as inhabitants scavenged plastic boxes, tires, satellite dishes and other useful materials.

While the ITS inhabitants have modified their tents, the landscape has proved less adaptable and provides little discernable benefit to residents. A row of trees, which remain from the previous agricultural use continues to fence in the settlement on one side without creating any shade to the benefit of the residents. The two swales that border the settlement have become dump zones and created serious health problems for the residents. No basic sanitation infrastructure to manage liquid or solid waste has been added to the camp despite high pollution levels and consequently mounting environmental and health risks to camp inhabitants. In 2014, Kayany Foundation, in collaboration with Center for Civic Engagement and Community Service (CCECS/AUB) and private donors built ‘Ghata’, a portable school on a site facing the settlement. ‘Ghata’ provides access to education to the children residing in Informal Tented Settlements and plays a major role in the lives of the kids who spend most of their day attending classes and playing in the playground. The communal open spaces are normally not paved and not equipped. They are no man land without the slightest form of communitarian sense that defines them as public space.

Water and soil pollution on Al Tyliani ITS is threatening the environmental condition of the neighborhood agricultural areas. Photo by Maria Gabriella Trovato.

Landscapes in Emergency

The International Operative Landscape Workshop e-scape was conceived of during a research symposium on Landscape in Emergency held in Beirut in January 2015 [4]. Al Tyliani was chosen as the site of the first workshop and intervention. In May of 2015, ten international professors and fifteen students spent eight days living and working in Al Tyliani.

The project had two primary goals. First, to formulate a definition of community attuned to the reality of refugee settlements in Lebanon. Second, while conducting fieldwork and learning from the Informal Settlement, we also sought to make a more direct contribution through the design and implementation of public space projects aimed at enriching collective imaginary and memory.

In light of an understanding of the weakened and fractured sense of belonging and cohesiveness in the ITS, we sought not to impose an artificial sense of community, but instead focused on physical projects whose planning and construction might themselves help foster connections and relationships among the individuals and groups in the settlement. We adopted Jean Luc Nancy’s definition of community as a network of singularities, a structure of shared life experience that is not “produced” but which evolves – emerges – in much the same way as the relationships of species in an ecosystem – built over time and layered through aggregation and by drift [5]. We tried to develop a landscape architectural strategy that enables communitas to evolve as an open system reinforced through the making of shared landscapes that are themselves open and evolutionary [6].

The inhabitants of the ITS were involved in the decision-making process from the beginning in the attempt to encourage them to take ownership of the public milieu. Workshops, meetings, and day-by-day discussions, helped visiting designers and camp residents to better understand each other and to work together.

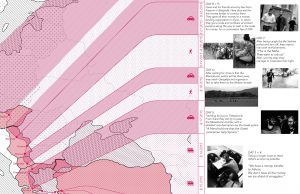

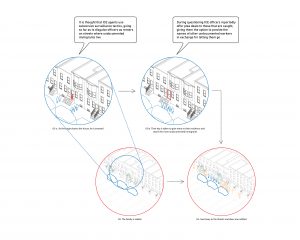

The first day, after a site survey and initial analysis, students mapped the settlement and diagramed the spatial organization and uses of open space. From our observation of the ordinary and everyday practices in place across the settlement, we began to better understand how the inhabitants reproduce the residential fabric of their original villages, creating nuanced layering of between public and private spaces despite the flat and homogenous nature of the Settlement’s design.

The very limited open areas between the tents are often fenced in order to be used to carry out the daily activities. Photos by Maria Gabriella Trovato.

Inhabitants regularly borrow public spaces for private uses along strict codes of acceptable behavior and temporality. The tacit appropriation of space adjacent to the tent regulates an acceptable extension of the domestic activity beyond home. In response to fluidity of behavior, the landscape itself becomes flexible and is constantly changing. Ephemeral territories are put in place over the course of the day only to disappear soon after without leaving any material trace. More permanent appropriation is present where the ratio between the tent and the open space disrespects the need to for privacy. Protection or buffering elements such as fabric or tarps are erected to block thresholds, preventing the passer-by from getting too close to intimate space.

In this way, structural and landscape elements are used to mark space and assert the possibility of ownership. The threshold, a thin and ultimately symbolic line (in the case of flimsy temporary tents), delineates at once an alienation of oneself from a collective whole, a distinction between identity and otherness. The flexibility and adaptability of this line is governed by well-defined spatial and social codes that determine the nature of the allowed domestic floods.

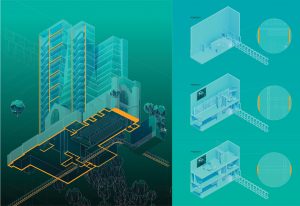

Based on the analysis and observation of the site, the group decided to focus on a network of three open spaces: a children’s playground, a pedestrian connection, and a water garden.

Maps and pictures of the three chosen open spaces in the ITS. Image by Maria Gabriella Trovato.

Three groups were formed and set to work sketching projects directly on-site. Our primary design criteria were usefulness to community, contribution to health and well-being, feasibility of construction, available materials, flexibility, and absence of maintenance.

The second day we organized a meeting with the community, inviting representatives from multiple constituencies including men, women, teachers, and children. We introduced ourselves and we explained our role and the scope of the workshop. We presented our understanding of the life in the settlement waiting for their feedback and asking for their contribution during the implantation phase. The community expressed their needs and desires and we agreed on the general projects and activities. The third day, we were joined by representatives from UNHCR Lebanon, during which we were able to share our observations on the conditions of the Settlement and our goals for the project while learning more about the context of the ITS and the UNHCR’s work to address the Syrian crisis in Lebanon.

The children’s playground project implementation. Photos by Maria Gabriella Trovato.

The projects that we chose to pursue were intentionally modest. But, they were achievable in eight days using cheap and recycled materials found on site. They required no specialty equipment or construction knowledge. This allowed for greater participation of community members in a participatory construction process. In 8 days we were able to transform the three discarded sites in community spaces.

The upgraded pedestrian connection. Photos by Maria Gabriella Trovato

In the children’s playground, we provided shady areas to gather during the day, equipped with simple and colored structures for children to play and enjoy their time. In the redesigned pedestrian connection, we re-graded the walkway between tents, creating a drainage channel and planted a rain garden. In the final space, we created a vegetable garden, creating beds for growing produce and flowers, a vertical structure for vines, and a shower game area for children to play while washing themselves.

The community participated in the implementation of all three projects: giving advice, helping with construction, carrying materials from one site to another, sewing, coloring and planting.

The rain garden project. Photos by Maria Gabriella Trovato

The design process was not linear and a lot of adjustments were made during the construction. Often, the community shared their feelings with our group indirectly. During the construction process, our team paid close attention to the reaction of the community to the new structures we were building. Sometimes, reactions were more direct – changes were sometimes made during the night and before our arrival to the settlement in the morning, helping us to simplify and clarify our ideas, providing opportunities for better understanding of the community’s rich culture through our daily interaction.

The final product was the result of collaboration between our expertise and their deep knowledge. The realized landscape projects were not a maquillage, a posteriori, but the operative test of a design methodology based on the immanent character of the landscape using it directly on the creative design process. With these small projects, we demonstrate that we can intervene on the existing, trying to mitigate the effect of the transformations made on the land designing a new landscape interpreting and using the elements on site in a continuous opera of writing and re-writing that could considers the mode of new insertion without compromising the existing.

Conclusion

If the ‘Landscape’ is eminently a cultural concept, the purpose of the research is to collect its many spontaneous expressions, which collectively form the Lebanese territory. These elements structure cultural identities and ultimately transform the landscape by creating new identities and experiences through the addition and overlap of a narrative. An understanding of existing cultural elements and their nascent meaning should influence and inform strategies of intervention at multiple levels, from municipalities to Ministries. The paper presents a case study of a design intervention that aims to contribute to the process of knowledge production and cultural understanding. The research is not exhaustive and is still in progress, but some trajectories were delineated and studied and hypotheses of guideline were written with the aim of helping the planning and territorial management of Lebanon.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to all those who are contributing to the Landscape in Emergency research. I would especially like to thank LDEM at American University of Beirut (AUB), IFLA, CCECS at AUB, Kayany Foundation, and UNHCR Lebanon for their valuable assistance, encouragement, and support to the research and their help on ground implementation. All the donors that practically allowed us to hold the two events. A special thank to my students for the efforts they put in and the capacity they shown in addressing a so difficult project. A particular gratitude to the professors who believed in the research, and, in spite of the difficulties encountered, are still interested in continuing the study. I want to thank my research assistant Hana Itani for her help and contribution to the project. I would also like to thank the many people who gave their time to inform this project. While I have purposely kept their input confidential, their voices are heard throughout this paper.

Maria Gabriella Trovato is Assistant Professor in the LDEM Department at the American University of Beirut. She has a PhD from the University of Reggio Calabria and the University of Naples in Landscape Architecture: Parks, Gardens and Spatial Planning.

Maria Gabriella Trovato is Assistant Professor in the LDEM Department at the American University of Beirut. She has a PhD from the University of Reggio Calabria and the University of Naples in Landscape Architecture: Parks, Gardens and Spatial Planning.

Maria Gabriella most recent researches focuses on MEDSCAPES project ENPI/CBCMED, on Landscape Atlas for Lebanon, and on Urban and Peri-urban landscape in the Middle East and North Africa. Actually she is working on Landscape in emergency research with special focus on Syrian crisis in Lebanon. She has worked in a number of countries including Italy, Morocco, Tunisia and Canada, and was lead partner in EU-research programs.