Ever since the industrial revolution, successive energy transitions restructured society and its systems, with new forms of energy enabling spatial and economic arrangements not previously possible or imaginable. First the was a shift from water and muscle power to coal and steam. Then, coal and steam gave way to oil and natural gas.

Today, driven by the climate crisis, the world is in the early stages of a new energy transition — from today’s dominant fossil fuel energy regime toward a renewable (or at least carbon-free) energy system. The form that this path to decarbonization will take is in no way preordained, but will be shaped by fierce battles over technological and political decisions within the energy sector and beyond. Addressing climate change will require a wholesale reimagining of society and economy. It is a design challenge of unparalleled scale and scope, demanding that we rethink how we produce energy, build cities, grow food, manage land, and transform labor. This, of course, is not just a conversation about energy infrastructure or carbon pricing. It is a conversation about the future that involves all of us.

In theory, the idea of an energy transition is fairly straightforward: an older fuel regime gives way to a newer one. In practice, energy transitions are far messier affairs, with multiple fuel regimes existing in parallel, producers and middlemen of competing energy sources battling it out for clients, new energy sources perhaps coming to define a certain energy regime, but older forms of energy rarely going away entirely. In Germany since the 80s, for example, energy policy has been dominated by the “Energiewende” — literally, the “Energy Transition” — which is widely seen around the world as a holistic national project that integrates German climate policy, industrial policy, energy development, and questions of labor. But while the German Energiewende has led to a dramatic expansion of offshore wind in the North Sea, it also kept lignite coal mines in former East Germany operating and Russian gas imports flowing.

The appearance of a newer energy regime doesn’t necessarily mean the disappearance of an older one. Here, oil production chugs along next to a major wind farm near Abeline, Texas. Video by Nicholas Pevzner and Stephanie Carlisle.

If adequately addressing the climate crisis is our goal, then what we’re interested in is not simply any energy transition, but a low-carbon energy transition, and we will need it to proceed more quickly and transform energy systems more radically than we have in any other energy transition in history. We can expect that such a transformation will be fiercely contested, as large established industries do not relinquish control without a fight. As geographers like Gavin Bridge have articulated, “it is, of course, precisely because of this potential to create new geographies of winners and losers that low-carbon transition faces opposition from those with a vested interest in the status quo.”

The emergence of new renewable energy technologies, along with their falling prices and growing power, has put increasing pressure on the incumbent fossil-fueled energy regime. Offshore wind turbines have kept increasing in size and efficiency, with GE’s gargantuan 260-meter tall, 12 megawatt Haliade-X turbines now undergoing testing and entering production. Photovoltaic solar energy with battery storage is about to become cheaper than coal power, or even than natural gas. But economic arguments can be easily undercut through politics and influence, which incumbent utilities and corporations have used in places like Ohio to avoid regulation, and then to subsidize coal-fired energy production that is no longer cost-effective.

What political mechanisms can be leveraged to accelerate the shift towards a low-carbon energy mix? As political scientists Hanna Breetz, Matto Middlenberger, and Leah Stokes have put it, “the politics of energy transitions are not one-dimensional conflicts between economic winners and losers. Instead, different political logics shape clean energy transitions at different stages of the experience curve. These political dynamics generate evolving pressures for policymaking and demand different levels or types of coalition-building among pro-transition groups” [1]. The politics of incumbency are powerful, are specific to the scale and maturity of each technology, and will test the organization and imagination of coalitions that arise to challenge the reigning fossil fuel industries.

The Santa Isabel wind farm near Salinas, Puerto Rico, which did not suffer damage after Hurricane Maria but remained largely curtailed months after the storm. Photo by Nicholas Pevzner.

Big Clean or Energy Democracy?

Infrastructure is always political, and energy transitions have always been contested, pitting established players against upstart technologies and new coalitions. This dynamic is further exacerbated when the question is not one of corporate competition, by a debate between radically different views of ownership, justice, and political power. Even if we see a wholesale switch to renewable energy, who will control this infrastructure and what form will it take?

Will the renewable energy future be a decentralized landscape of small energy cooperatives and individual owners? Or will the future privilege large-scale renewables — massive offshore wind farms, colossal concentrating solar “power towers,” and expansive fields of photovoltaic arrays — achieving decarbonization without fundamentally upending corporate control? Will the renewable energy future continue to be dominated by a greener and more diversified Chevron, ExxonMobil, and BP, the very corporations responsible for the bulk of historic carbon emissions? Will large utilities and energy companies continue to have unquestioned sway, or will they be made to compete on an even playing field with community-owned energy co-ops and nonprofit entities, or even be nationalized or municipalized and brought into public ownership, eliminating their profit motive for good?

These, of course, are questions of power: who has it, who gets to decide who has it, and what they do with it once they have it.

Solar recently installed on rental apartment buildings in Queens, New York City. This system consists of 552 panels across four buildings, saving the building owners about 70% on their energy bills. Photo by Nicholas Pevzner.

The concept of “Energy Democracy,” [2] meanwhile, posits that people and communities have a right to control their energy futures and that transformative and radical change will only happen through a shift from a profit-driven energy industry to democratic control and social ownership of energy resources, infrastructure, and options. As defined by Sean Sweeney, Kylie Benton-Connell, Lara Skinner in a 2015 report of the Trade Unions for Energy Democracy Initiative, “Energy democracy is about workers’ and communities’ ability to decide who owns and operates our energy systems, how energy is produced, and for what purpose” [3]. It stands in sharp contrast to both the business-as-usual case of control of energy systems by for-profit companies and marketized state-owned utilities, as well as a more liberal strategy of renewable energy by any means necessary, common to mainstream environmental groups and government agencies. An example of this approach is the dozen U.S. states that have developed community solar projects, where mid-sized solar generation projects enable community members own or lease shares — letting people profit directly from their renewable energy production and decentralizing decision-making over energy down to the community level.

For some, justice is largely about economics and who seeks to gain from the falling costs of renewable energy infrastructure. As the energy regime begins to shift to non-fossil sources of energy generation, what happens to the idled fossil fuel workers? How can the refashioning of economic systems be used as a tool to bring everyone along into a more equitable future? As an example, Germany has produced a policy designed to help coal miners idled by the eventual phase-out of lignite coal production [4]. In the United States programs to extend opportunities for retraining and tech education have been met with mixed feelings. Advocates of intersectional climate justice, including many arguing for the Green New Deal framework, have embraced the idea of a just transition for fossil fuel workers and other polluting industries, seeking to grow an expanded array of well-paying jobs in the renewable energy sector and across the new low-carbon economy.

The lens of environmental justice can be useful beyond simply considering the economics of profit and wage labor. As Benjamin Sovacool and Michael Dworkin, the authors of the book Global Energy Justice, write, “People are starting to recognize that the world of energy involves fundamental ethical questions” [5] Energy justice, therefore, “calls for a moral examination of energy systems,” [6] rooted in law and in sociology, and in understandings of social justice and social inequality.

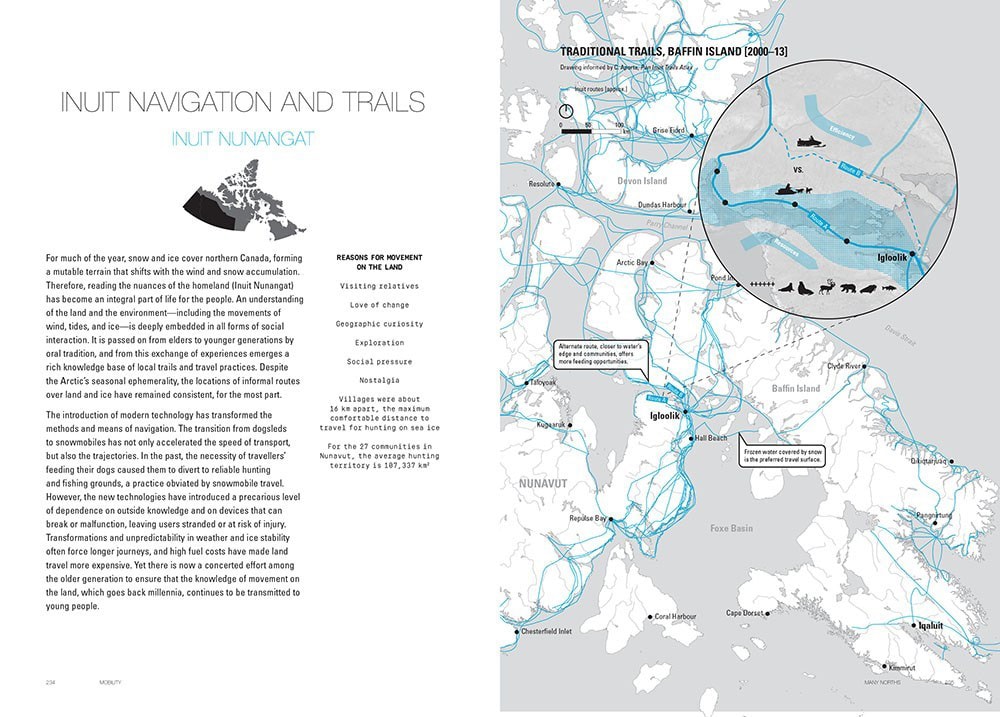

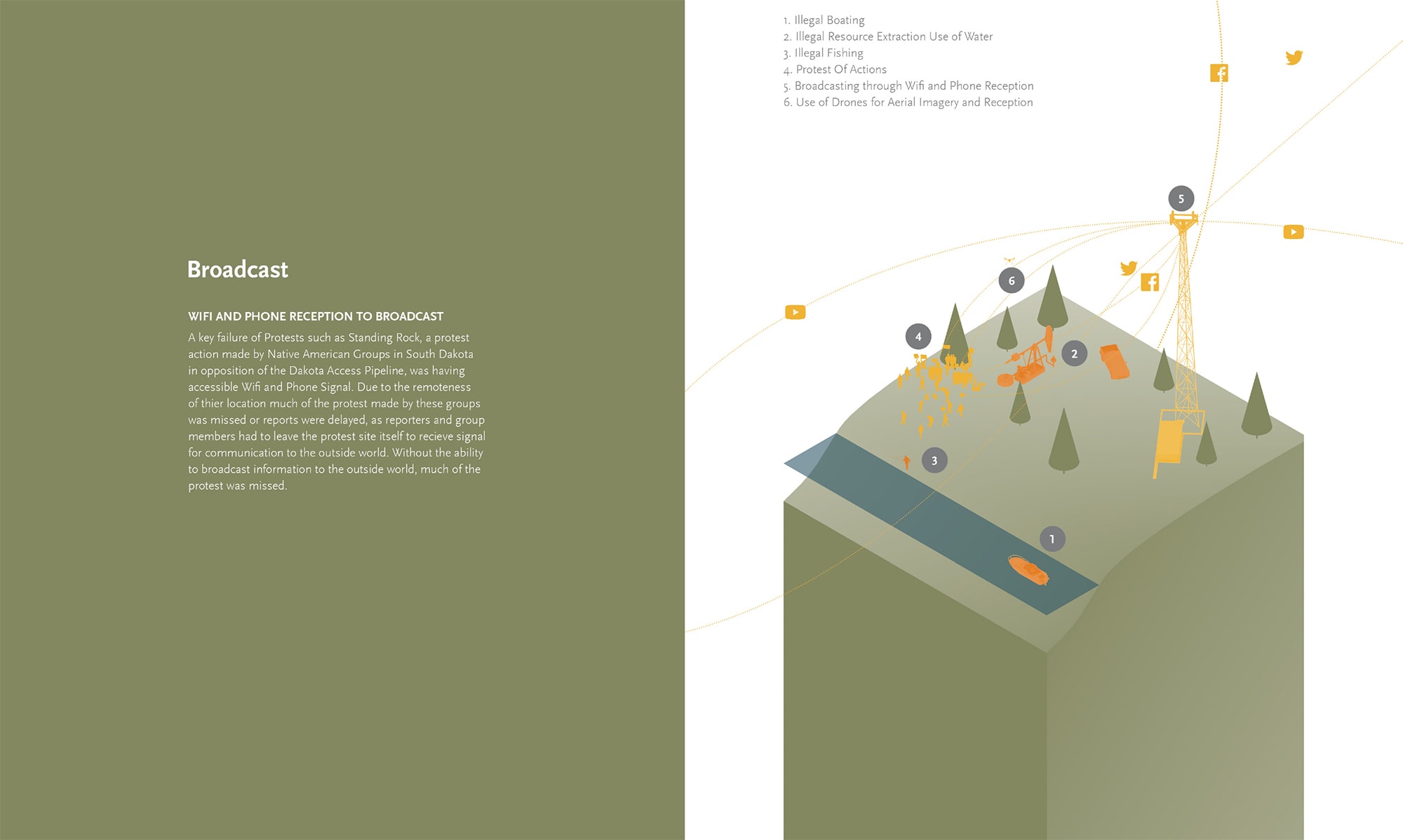

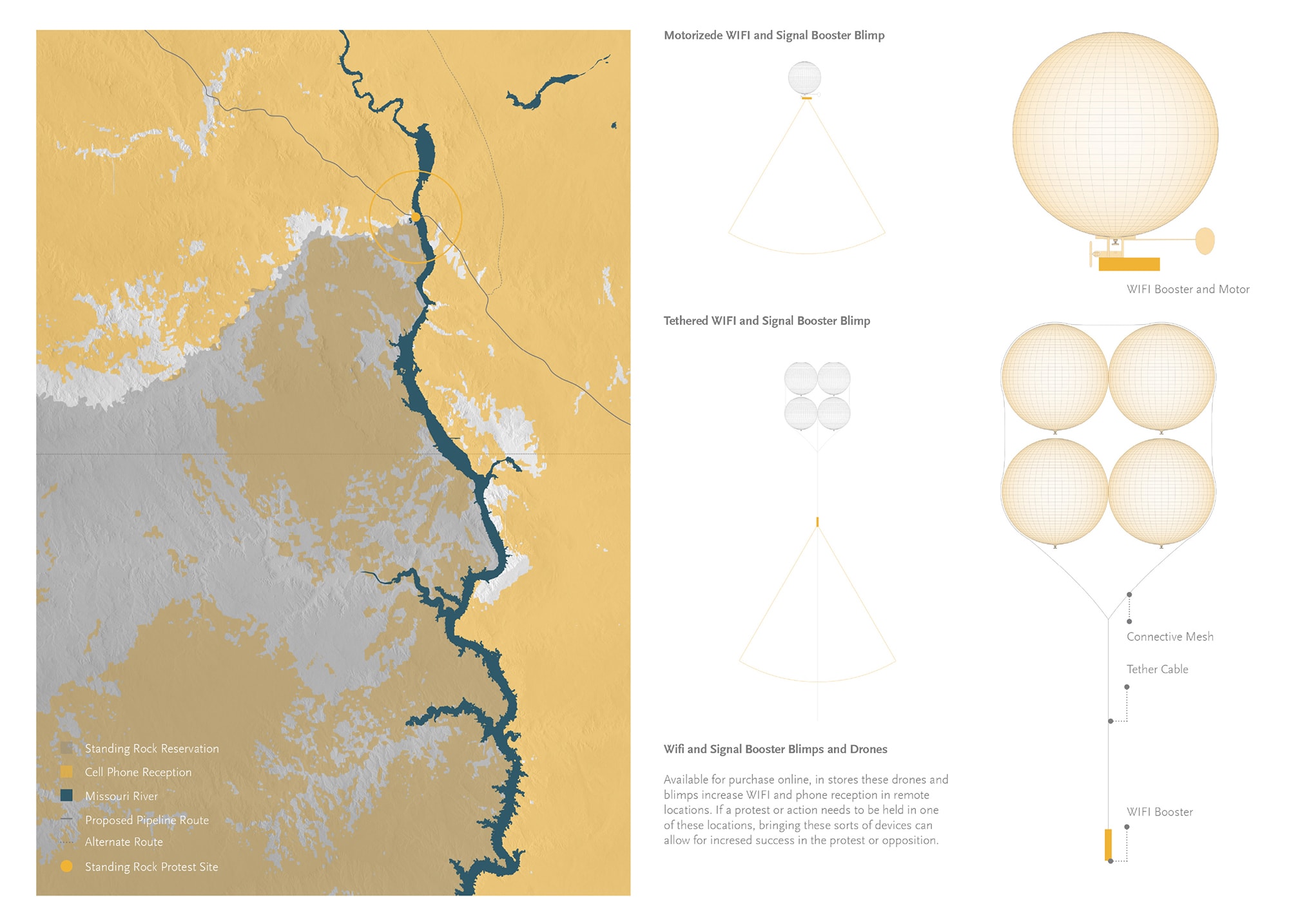

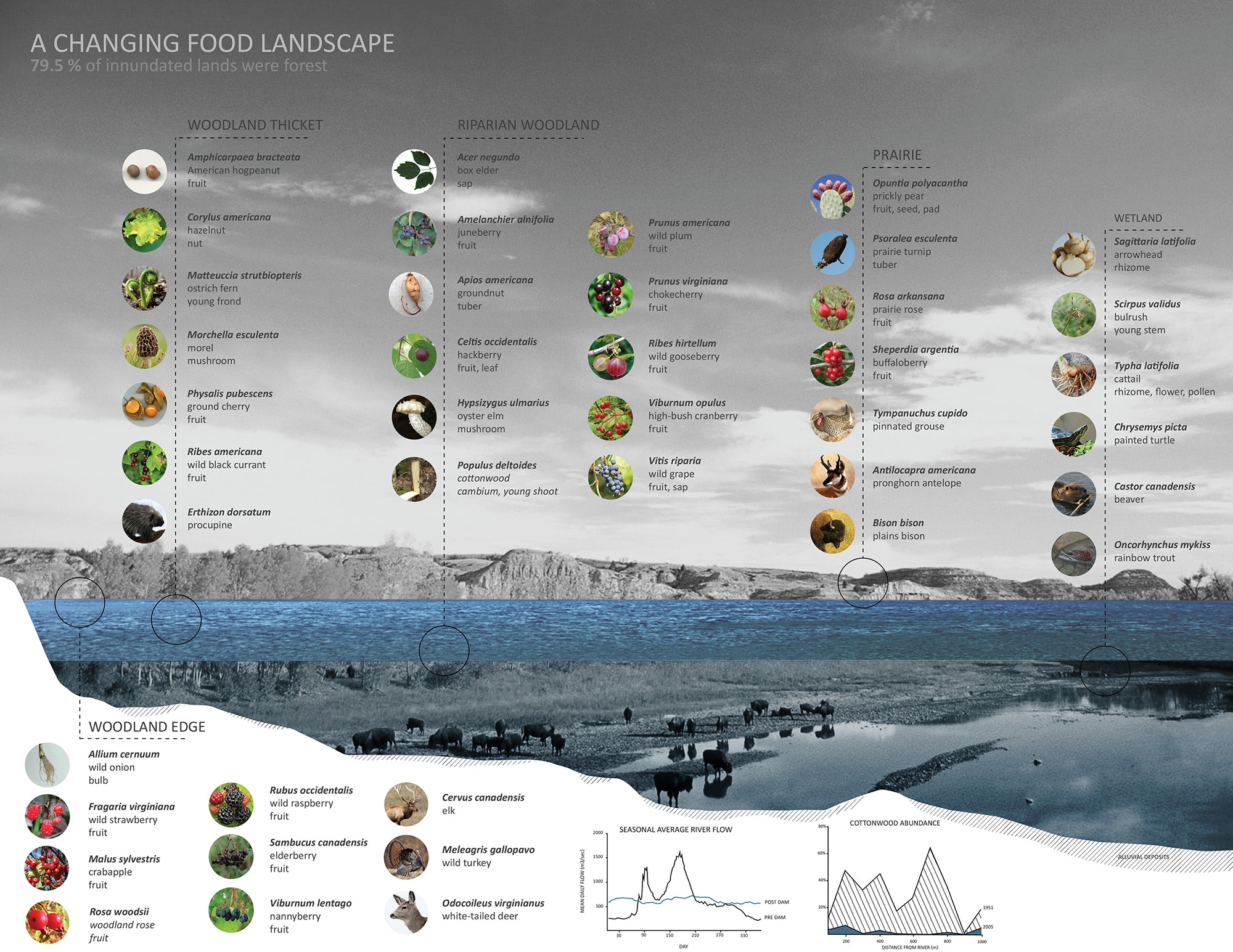

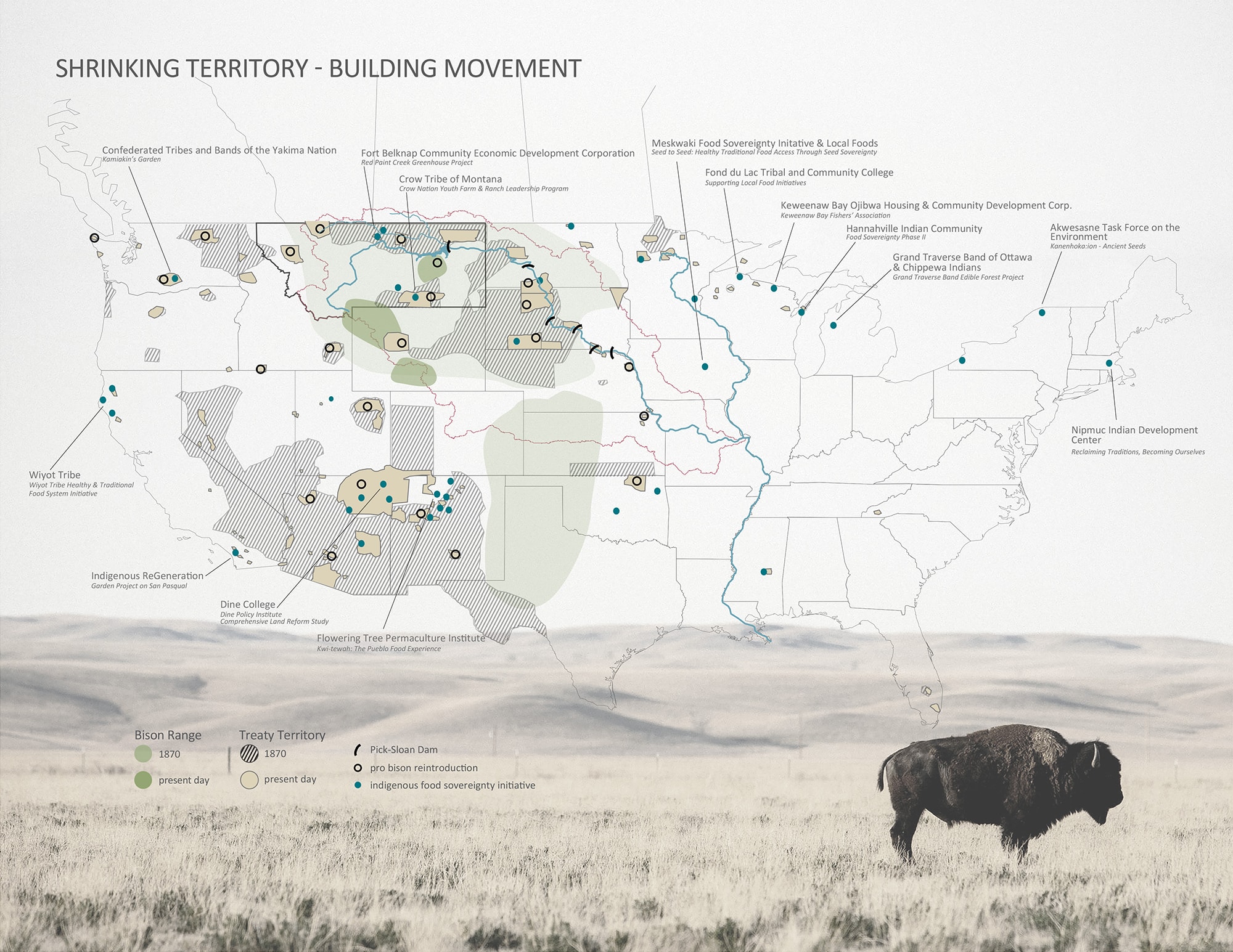

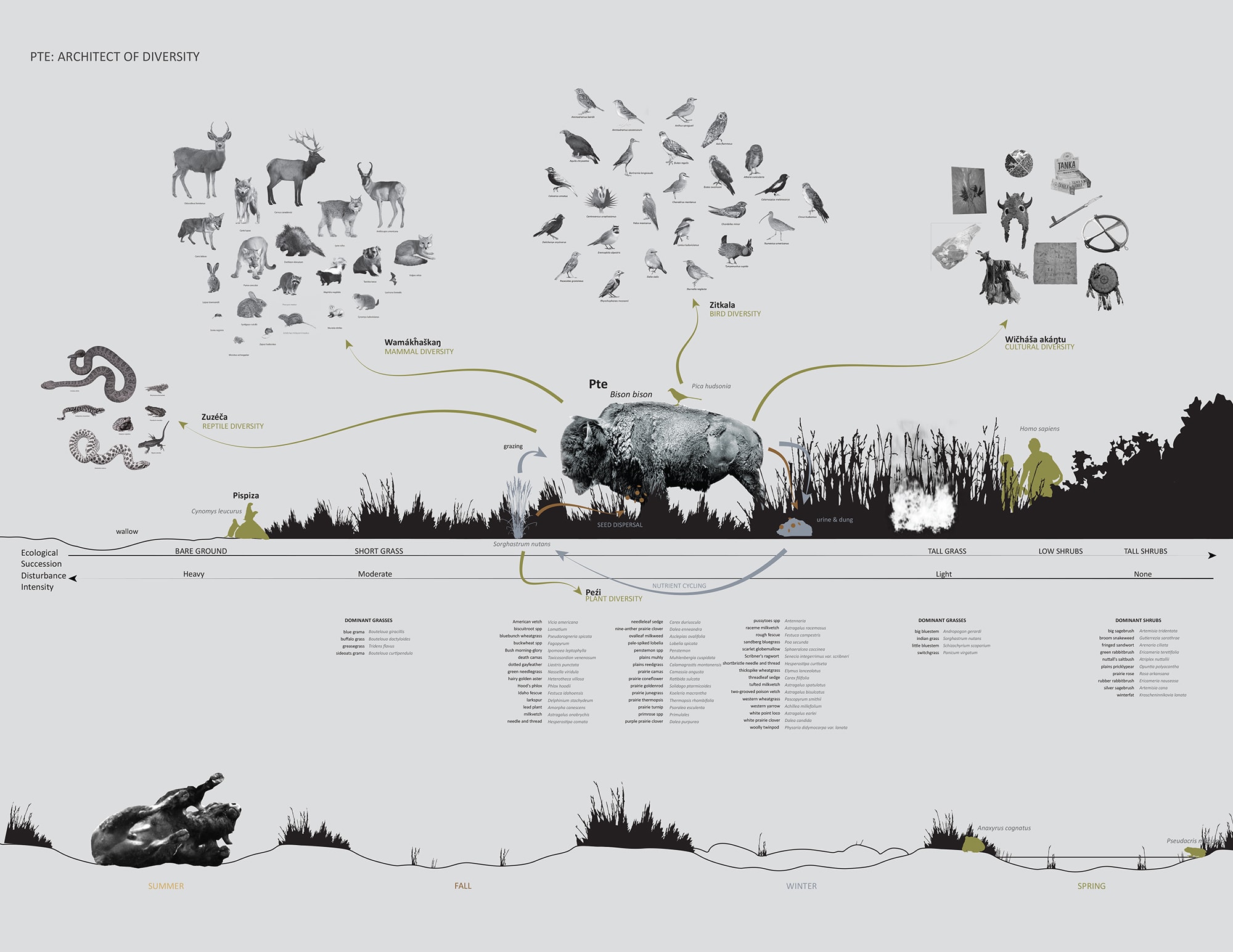

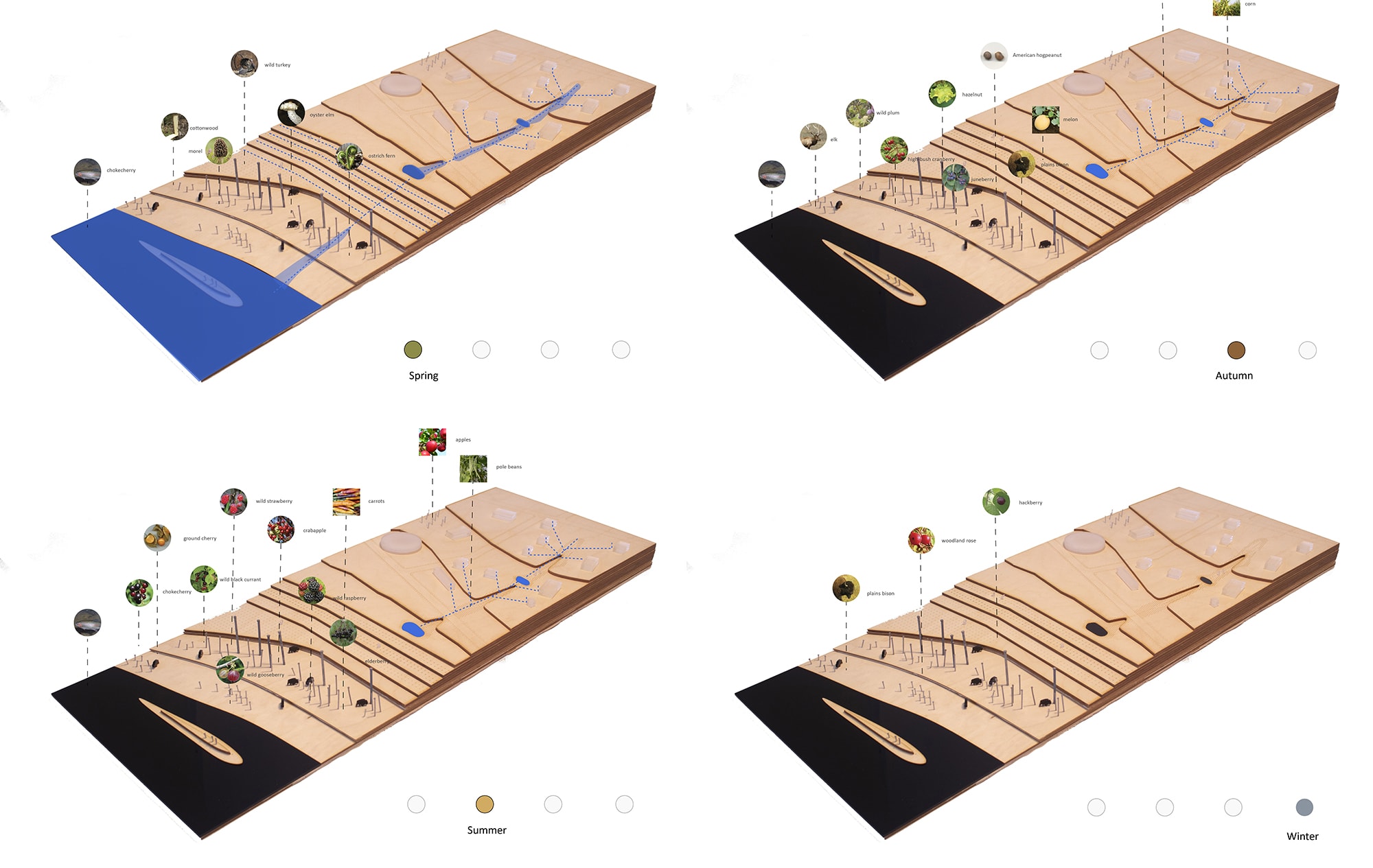

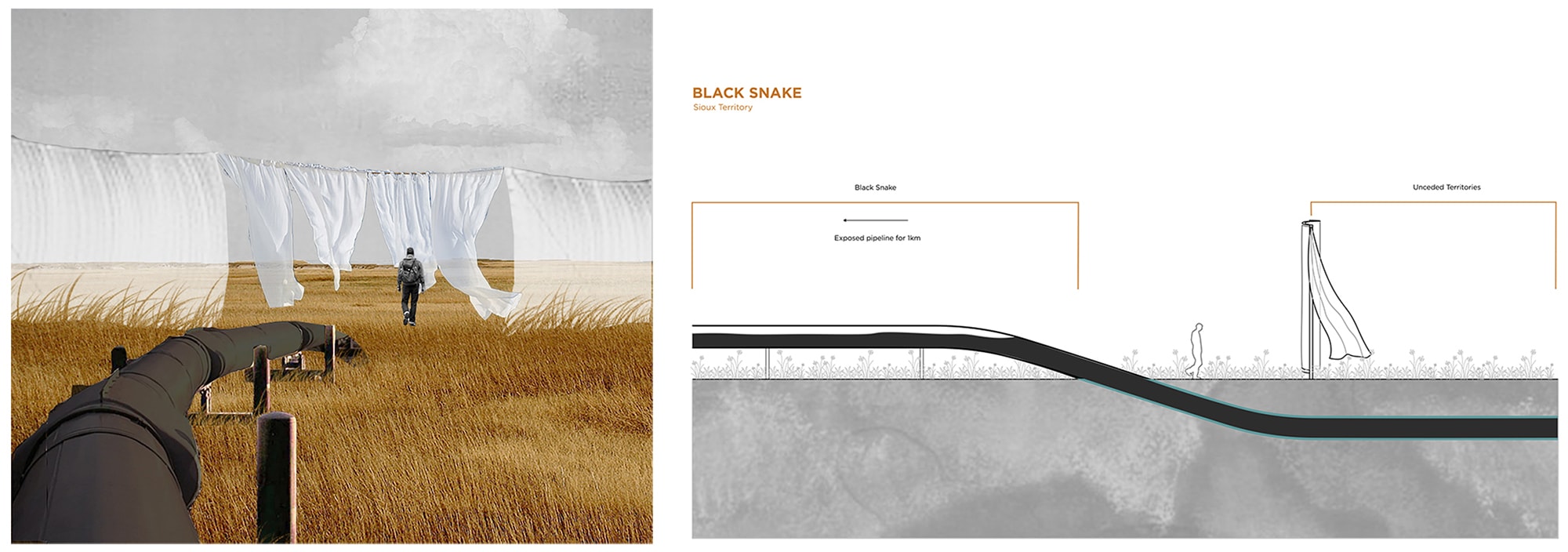

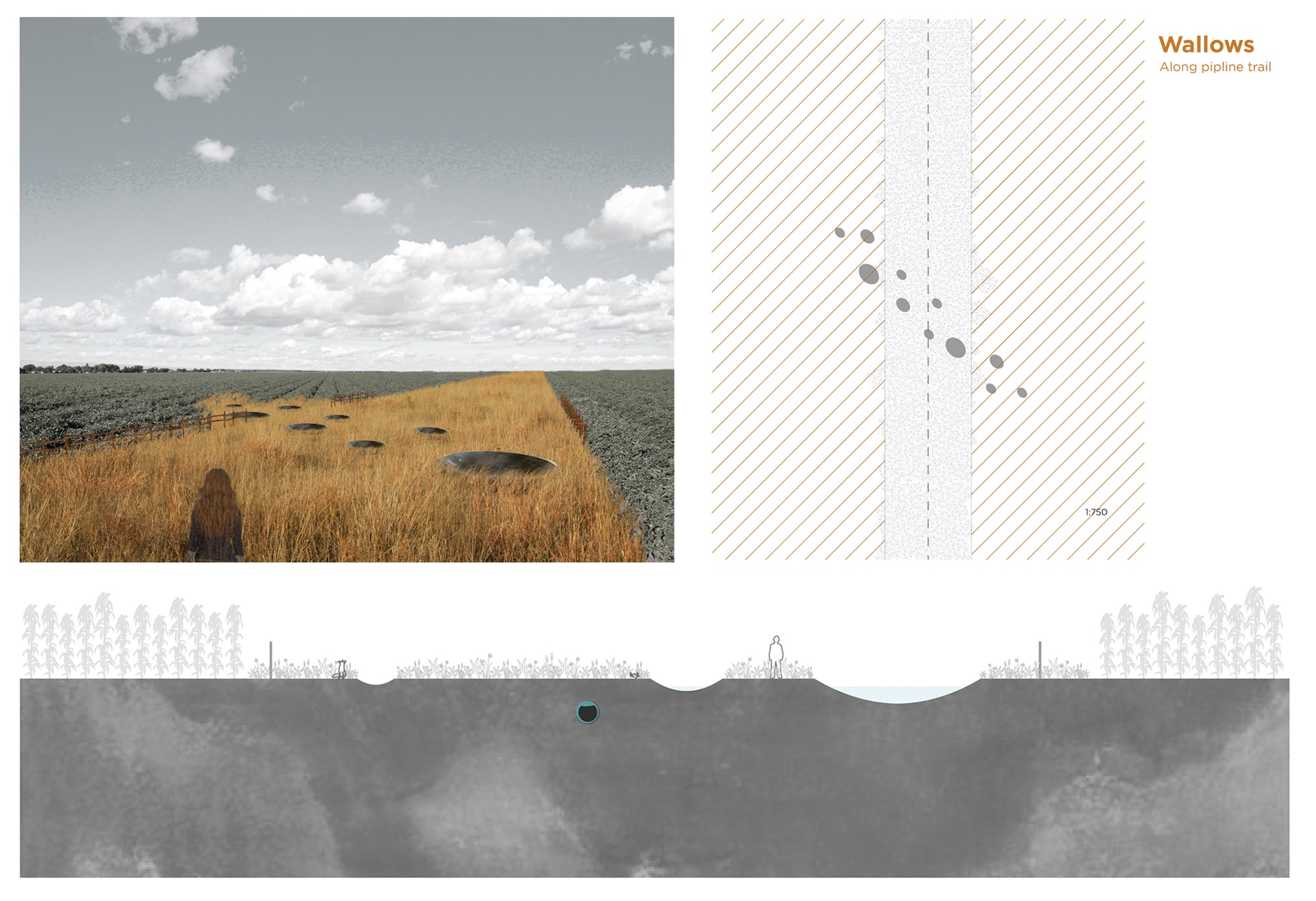

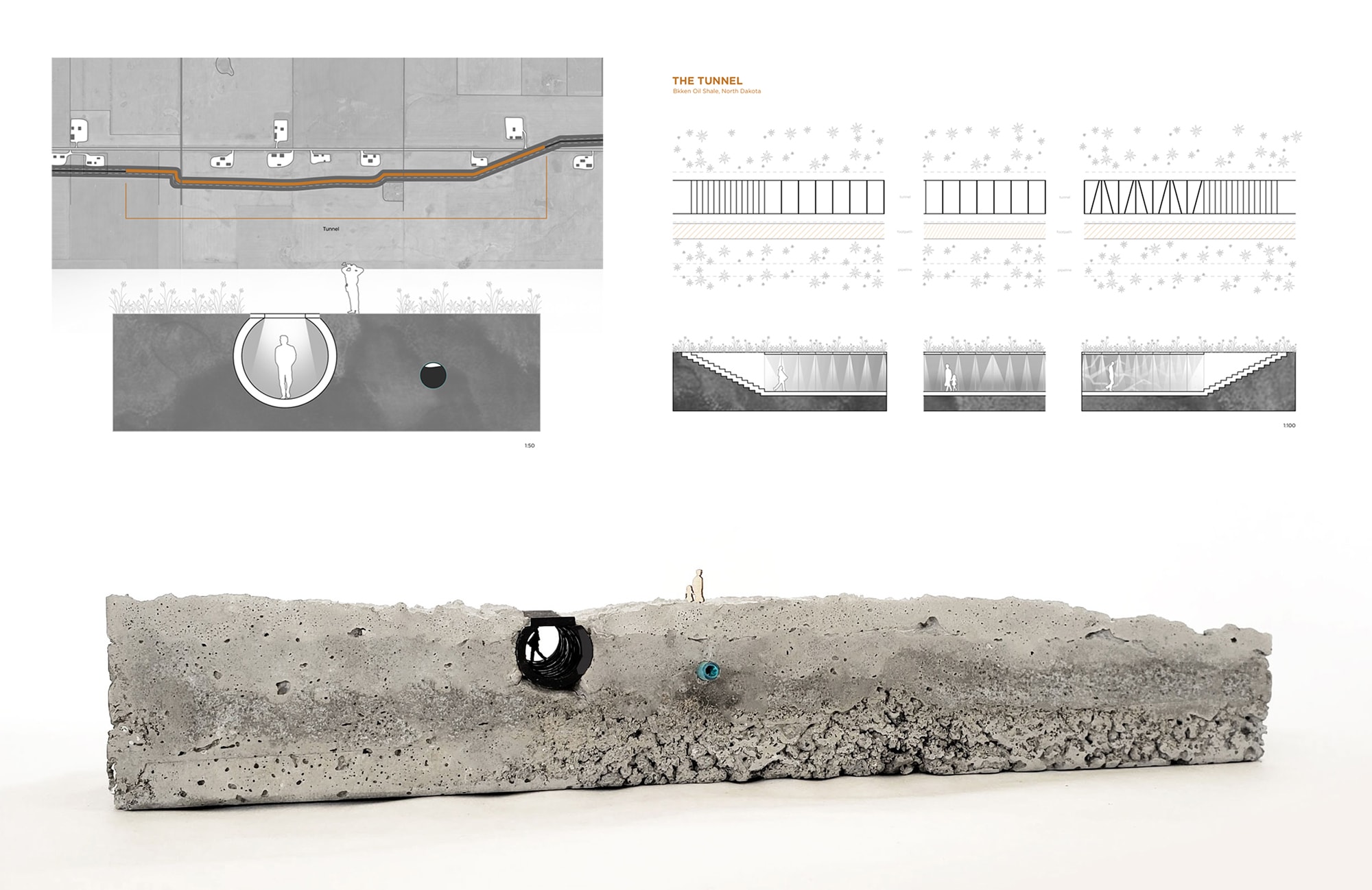

Indigenous resistance to fossil fuel infrastructure should cause us to expand our notion of historic and present-day injustices and the limited set of values by which most infrastructure projects are judged. The recent waves of indigenous-led protests against fossil pipeline infrastructure in North America [7] have highlighted the climate risks, broader ecological harms and neocolonial undertones of these projects and the madness of endless fossil fuel extraction. This opposition has grown into an opposition against all forms of fossil fuel infrastructure and “keep it in the ground” campaigns.

Renewable energy is not exempt from environmental impacts or social inequity. Similar resistance has grown around the world with indigenous communities pointing to the decimation of indigenous fishing grounds by hydroelectric dam construction across Brazil, or the appropriation of groundwater in the Atacama region of Chile by rapidly expanding lithium mines that supply raw materials for lithium-ion batteries. Indigenous communities are organizing to push back “against ‘green extravisim,’ the subordination of human rights and ecosystems to endless extraction in the name of ‘solving’ climate change” [8]. Decolonizing the power sector is critical if social justice is to be a serious part of the renewable energy transition. Several pieces in this issue offer both historical context and tools for decolonizing design practices and energy landscapes.

The concepts of energy democracy and energy justice help us see that energy transitions, are societal transitions, and decisions about energy infrastructure and the design of cities and manufacturing can either reinforce existing power dynamics or challenge them. A radical transformation of energy infrastructure and the economy will create unprecedented opportunities for an inclusive and participatory conversation about climate change and social justice. It is exactly at such time that we should be asking, “who has the power to talk about infrastructure, and who gets left out?”

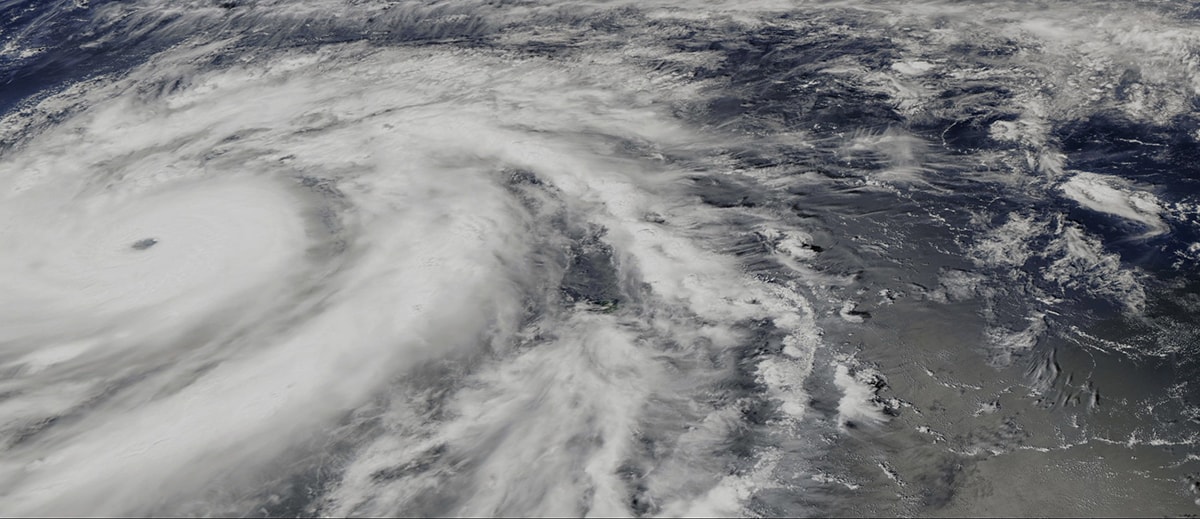

The Punta Lima wind farm in Puerto Rico, destroyed by Hurricane Maria.

The Essays

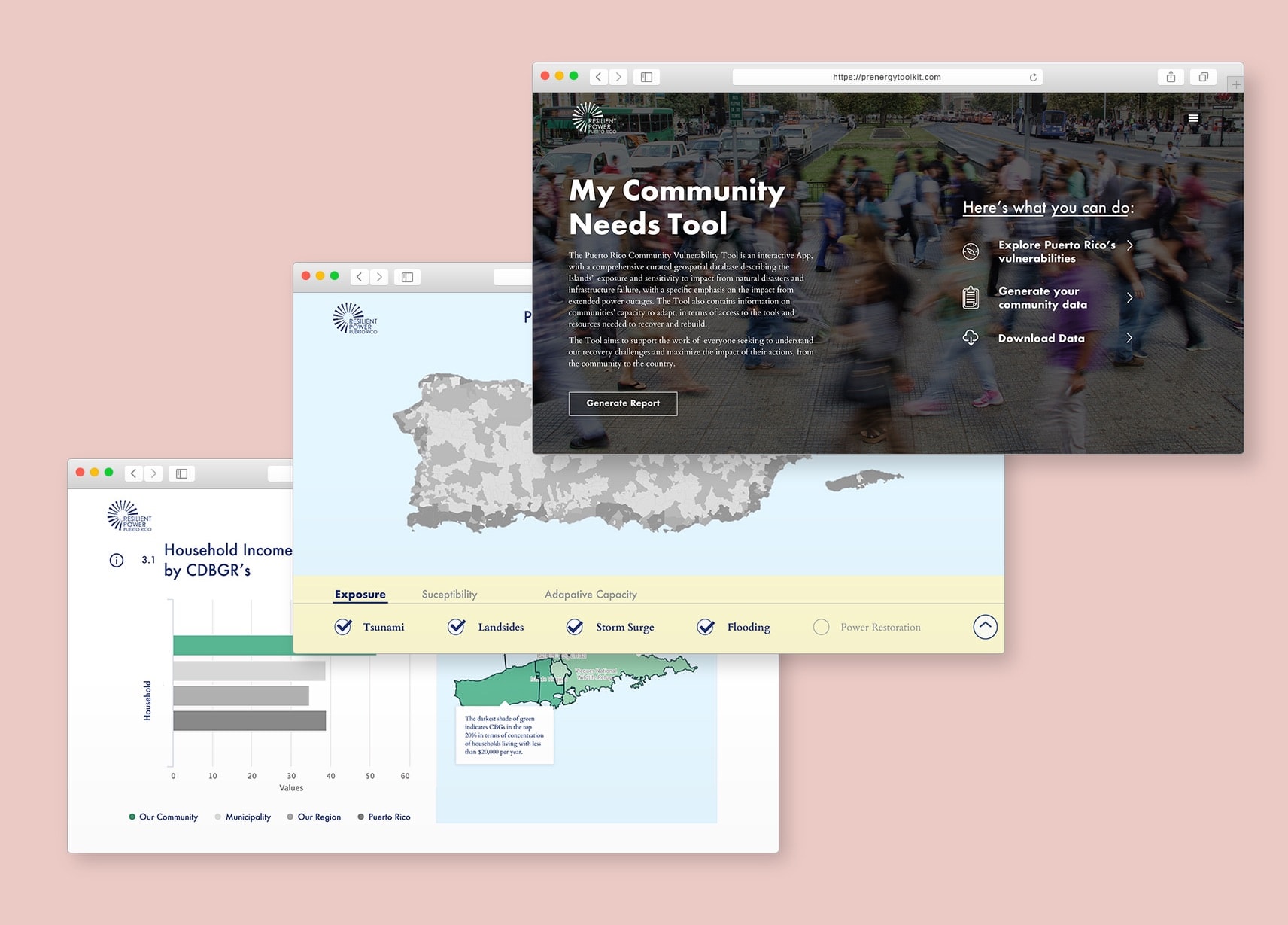

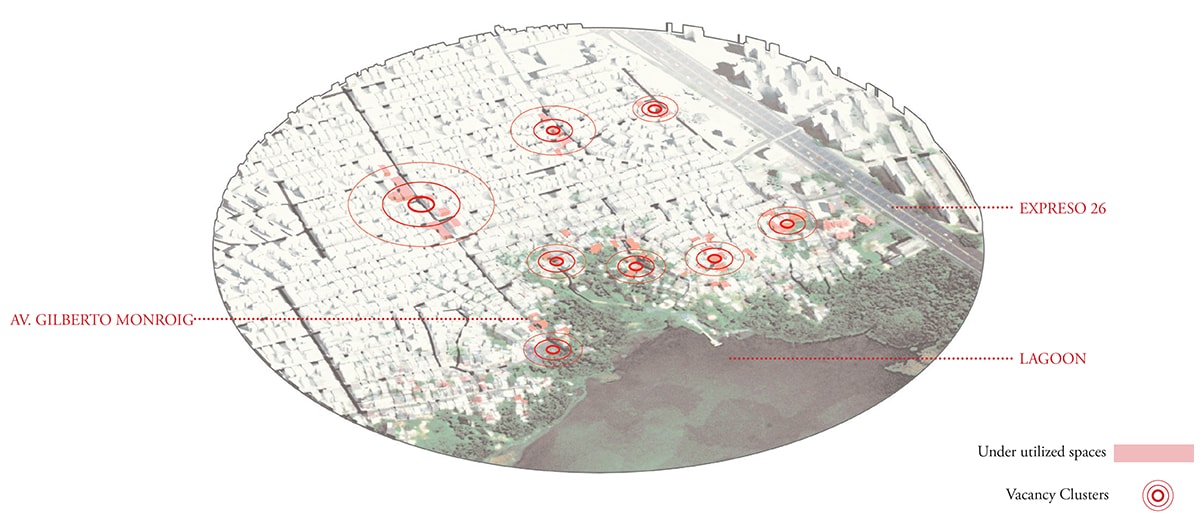

Puerto Rico has emerged as a central battleground in the showdown between the old centralized patterns of energy and emerging models of decentralized and communitarian energy production. During Hurricane Maria these players utterly failed the energy demands of the people, while afterwards redirecting the recovery assistance towards recovering their own political dominance and control. While the struggling and debt-ridden centralized utility pushes a transition to natural gas infrastructure, communities around the island are experimenting with solar-powered energy and cooperative ownership.

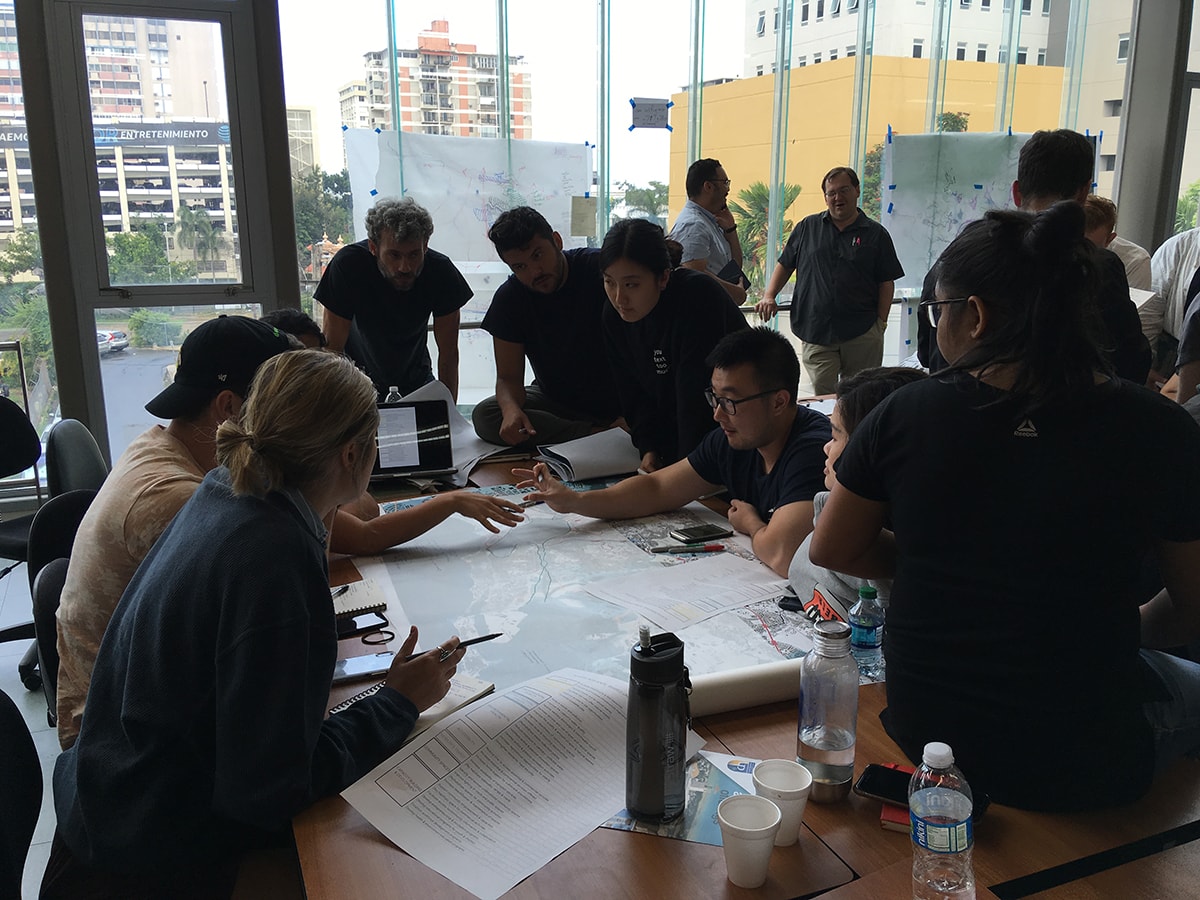

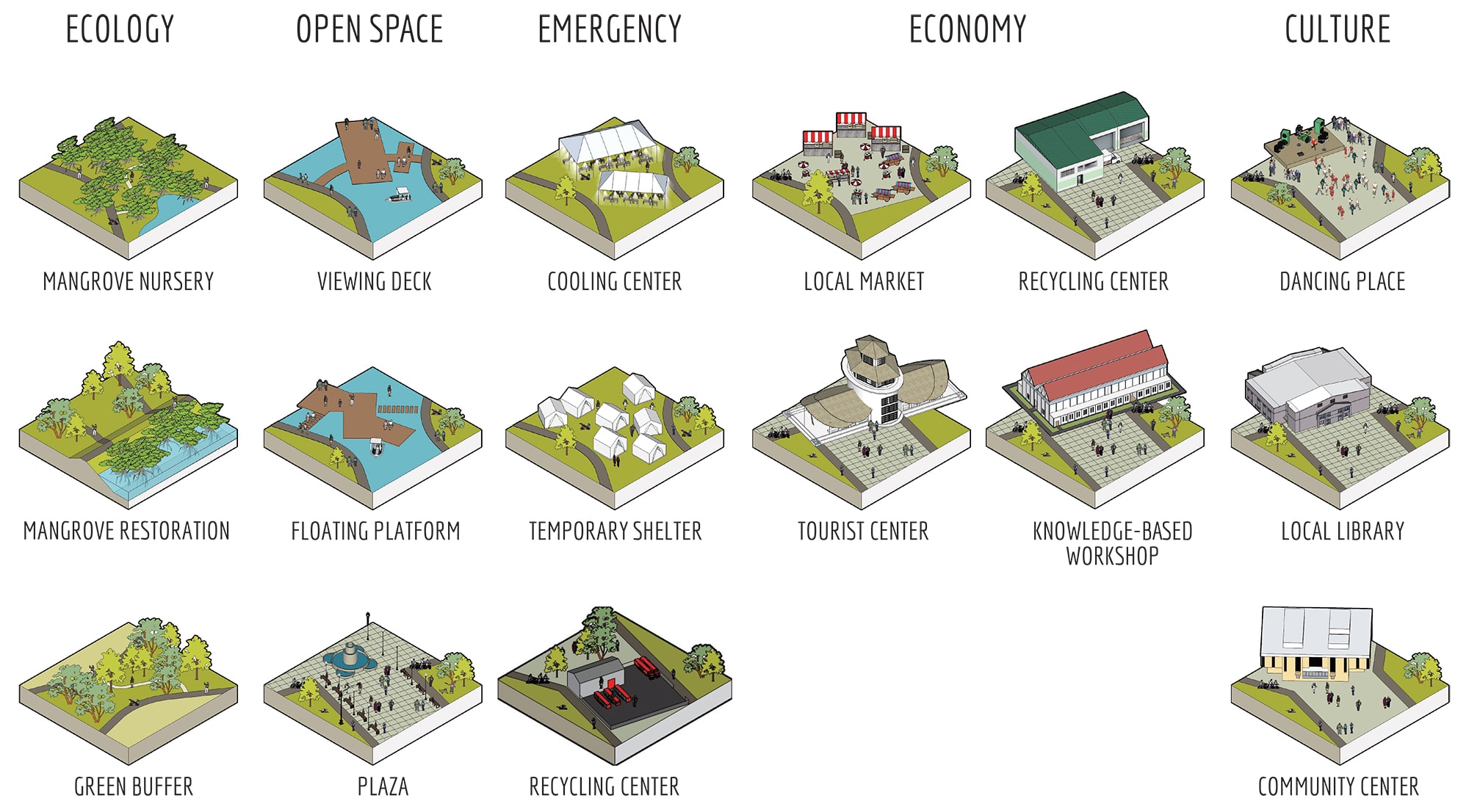

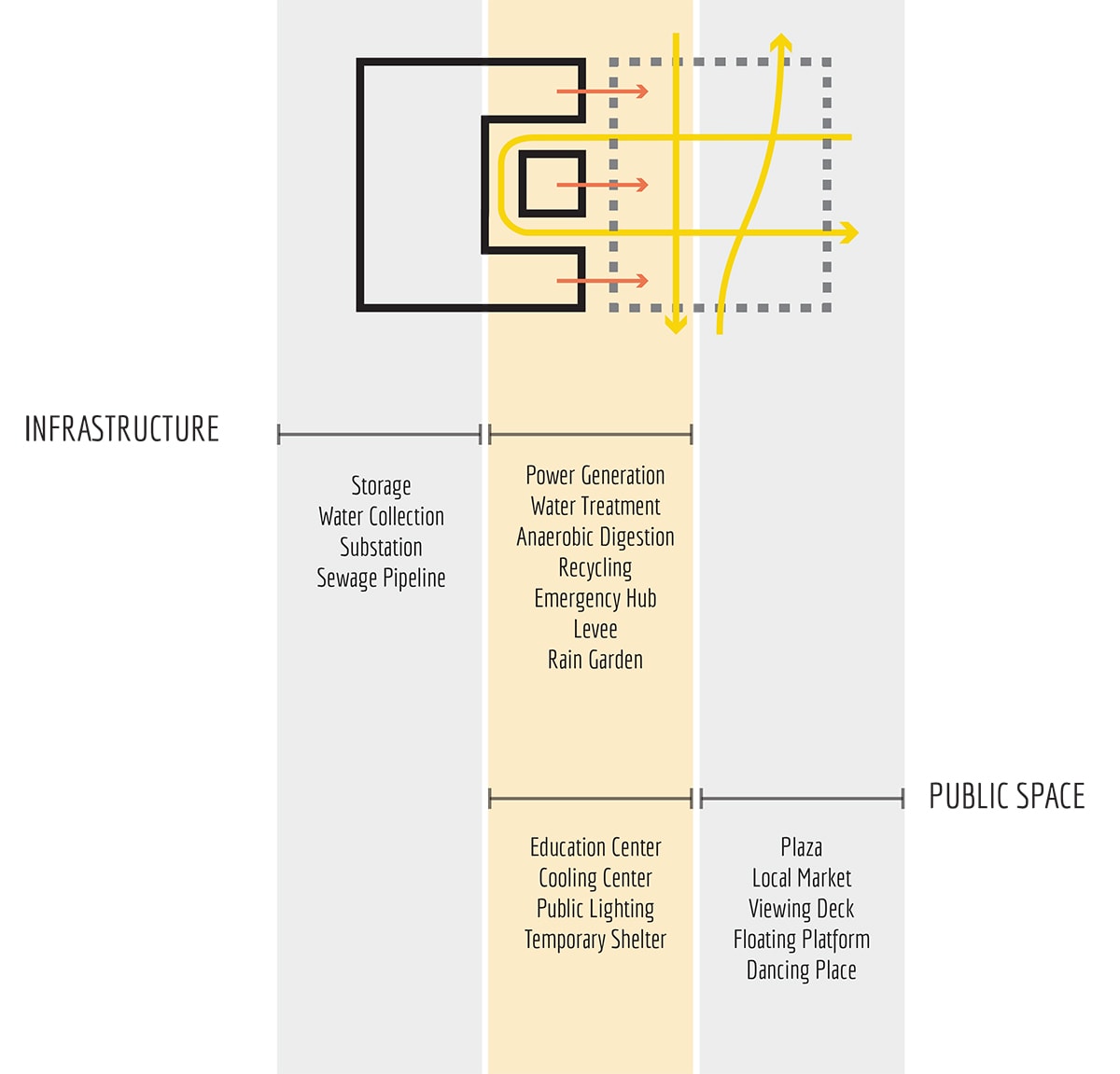

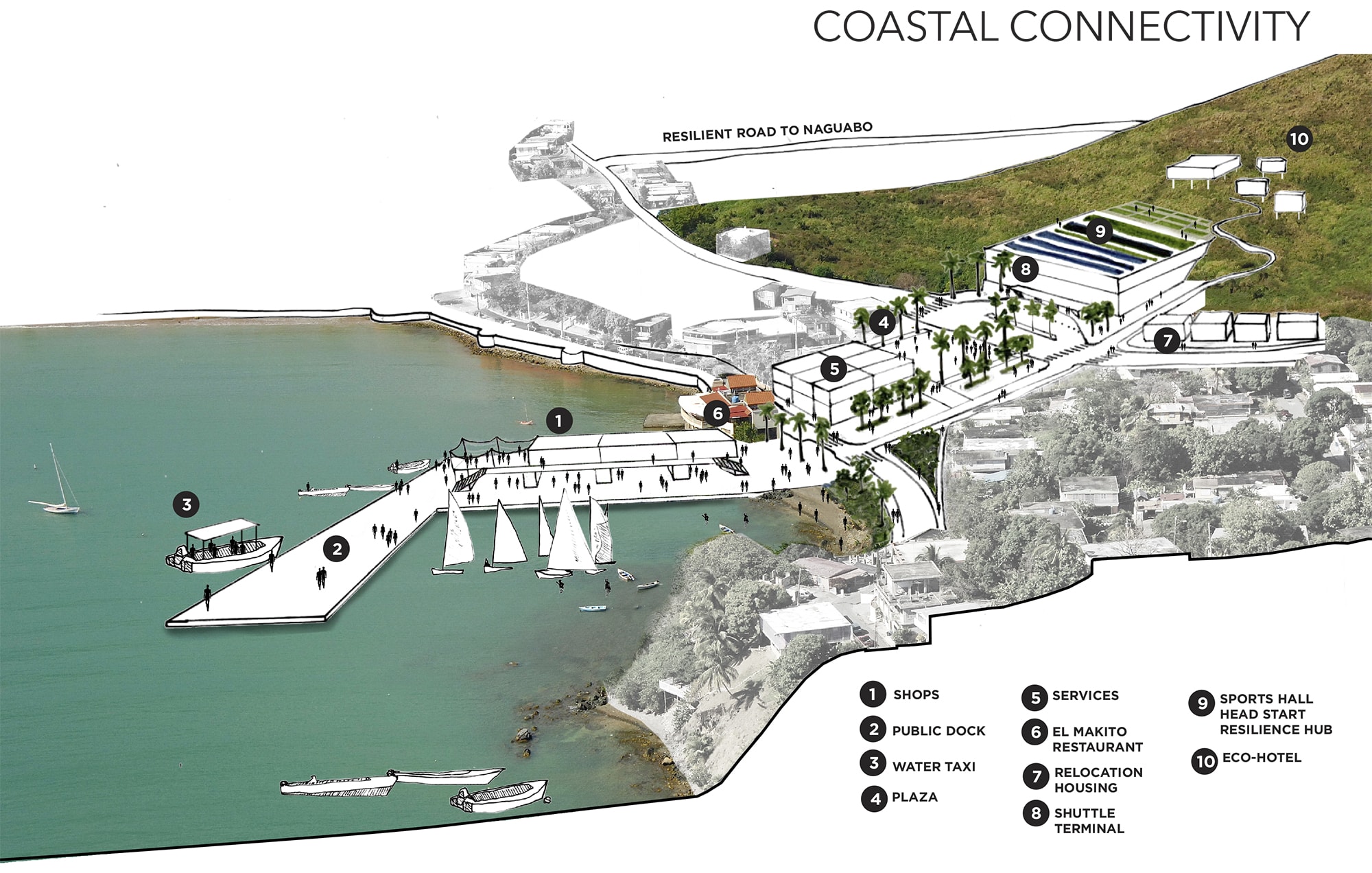

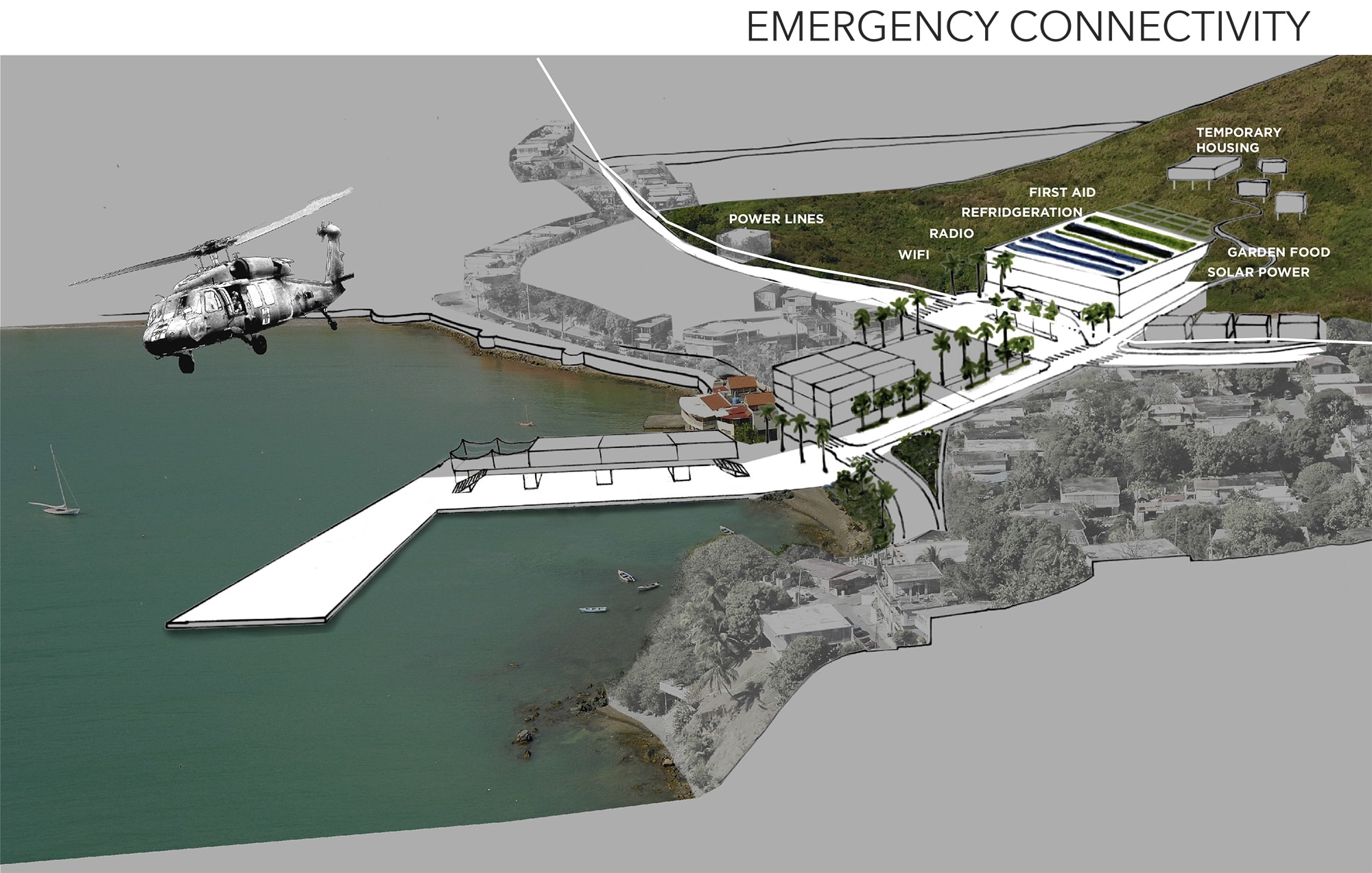

Appropriately, this issue dedicates several pieces to the energy situation in Puerto Rico, highlighting a few of the different strategies that communities are pursuing in search of energy democracy and energy justice. José Juan Terrasa-Soler and Daniela Lloveras Marxuach highlight the role of nonprofit Resilient Power Puerto Rico in providing solar energy for communities across the island in the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Maria, empowering communities with a combination of hardware and knowledge. Arturo Massol-Deyá describes the work of Casa Pueblo, a nonprofit community environmental center, in provisioning solar energy for critical services within the town of Ajduntas as an explicit rejection of the centralized utility’s energy strategy. Nicholas Pevzner offers examples of speculative landscape architecture design that can support a system of community-run energy production in Puerto Rico that can start to build community resilience and community power.

The oil- and gas-burning Aguirre Power Plant in Salinas, Puerto Rico. Photo by Nicholas Pevzner.

With power infrastructure, we typically picture the physical infrastructures of energy production. While the power plants, dams, turbines and smokestacks are the most visible elements of the power grid, the grid is a much more complicated entity — it has been called “the world’s largest machine and the twentieth century’s greatest engineering achievement” [9]. The energy grid consists of power stations large and small, millions of miles of wire, all connected together and managed in real-time from a handful of control centers, one power surge away from tripping up and going down. Political theorist Jane Bennett has called it “a volatile mix of coal, sweat, electromagnetic fields, computer programs, electron streams, profit motives, heat, lifestyles, nuclear fuel, plastic, fantasies of mastery, static, legislation, water, economic theory, wire, and wood—to name just some of the actants” [10].

One of the most critical and overlooked element of the grid, in the context of the renewable energy transition, is the system of transmission lines that move the power from the sites of generation to the centers of consumption [11]. In our current moment of climate-induced stress, overhead transmission lines have emerged as a major point of weakness in the grid, as well as a major barrier to scaling up renewable energy. Around the world, new high-voltage transmission lines are seen as necessary to support a build-out of renewable energy. While in the U.S., bold early nation-wide efforts to transform the transmission system have largely ended in failure, as documented in Russel Gold’s recent book SUPERPOWER [12], other countries, such as China, are rapidly modernizing their transmission systems, extending them across vast distances, and, as James Temple describes in his piece, doing so in a way that furthers the Chinese state’s power.

Photo by zorori47

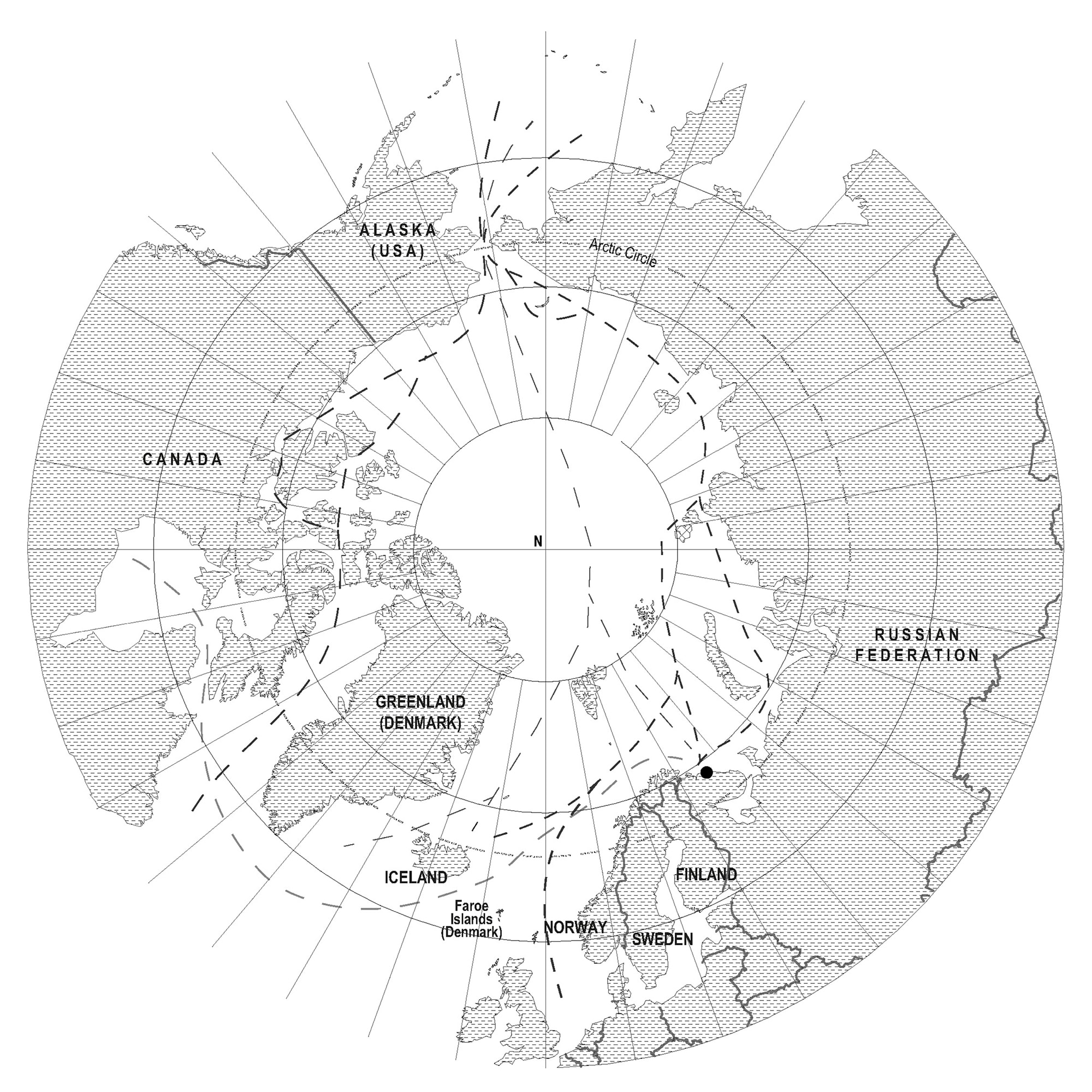

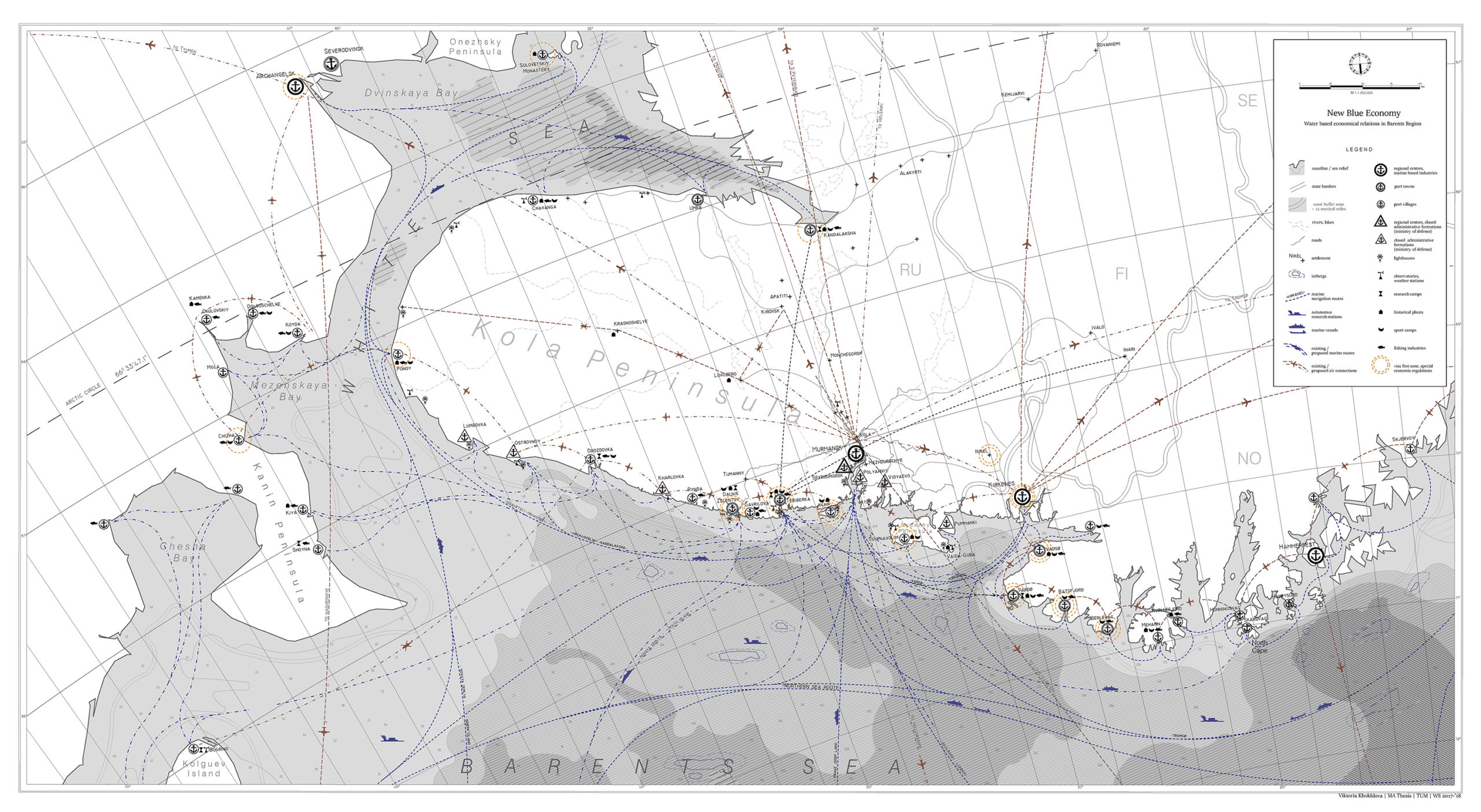

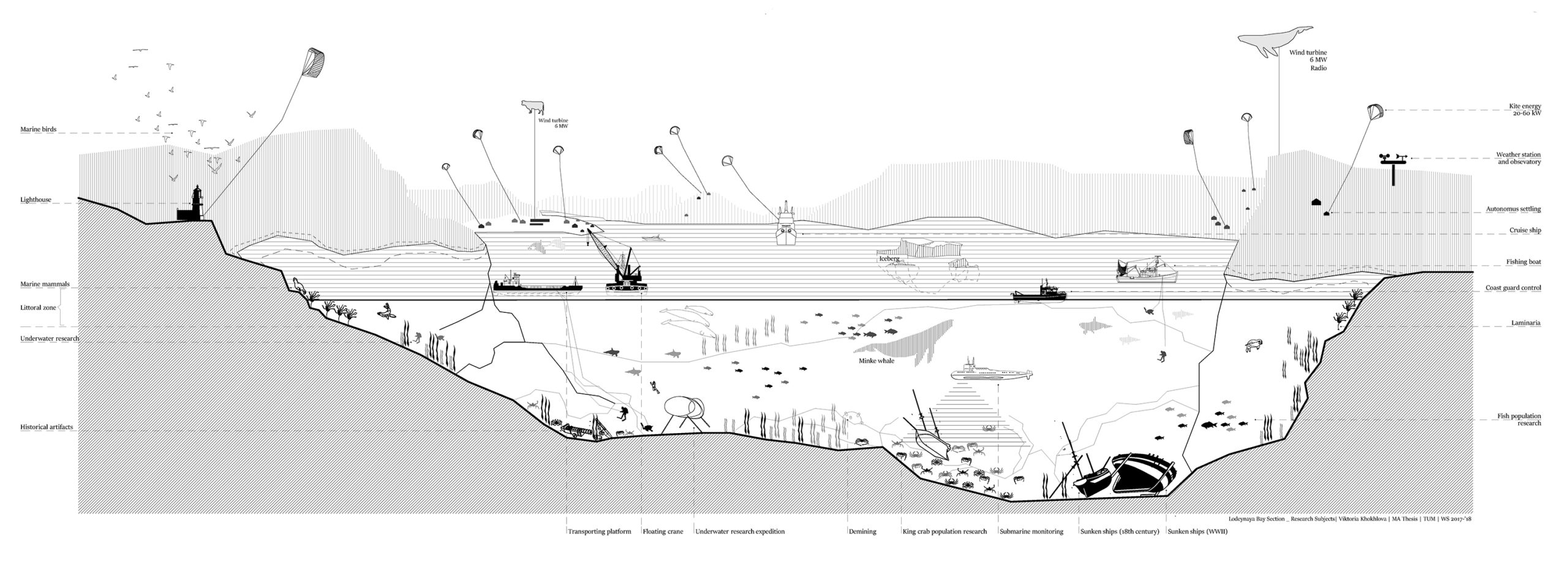

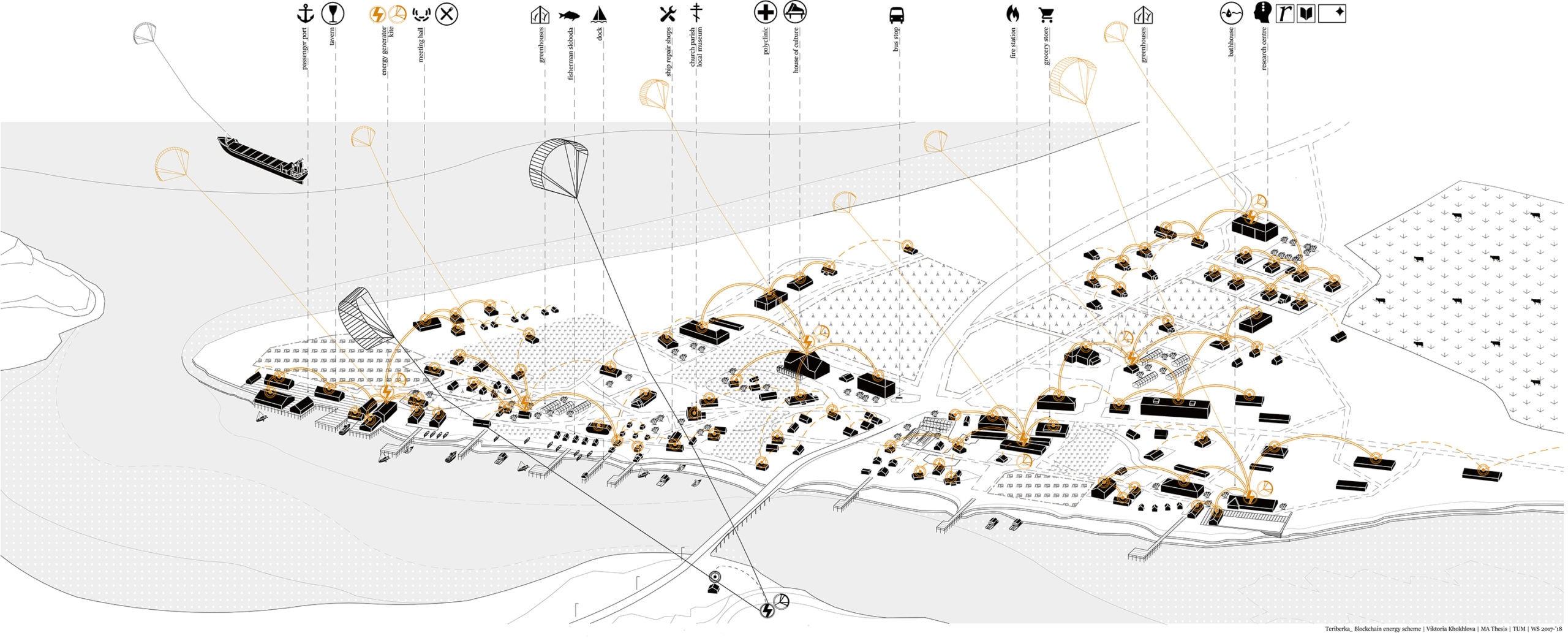

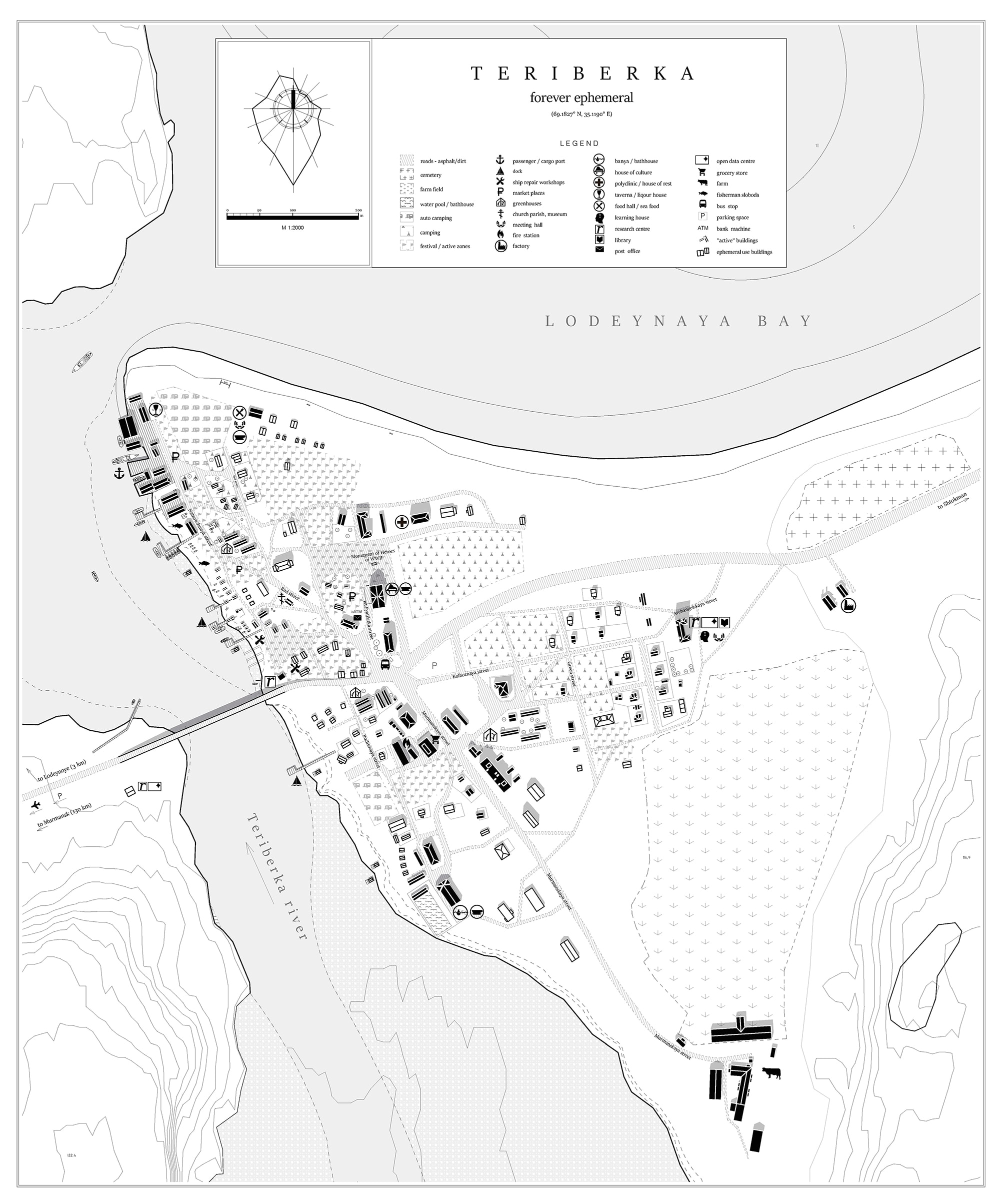

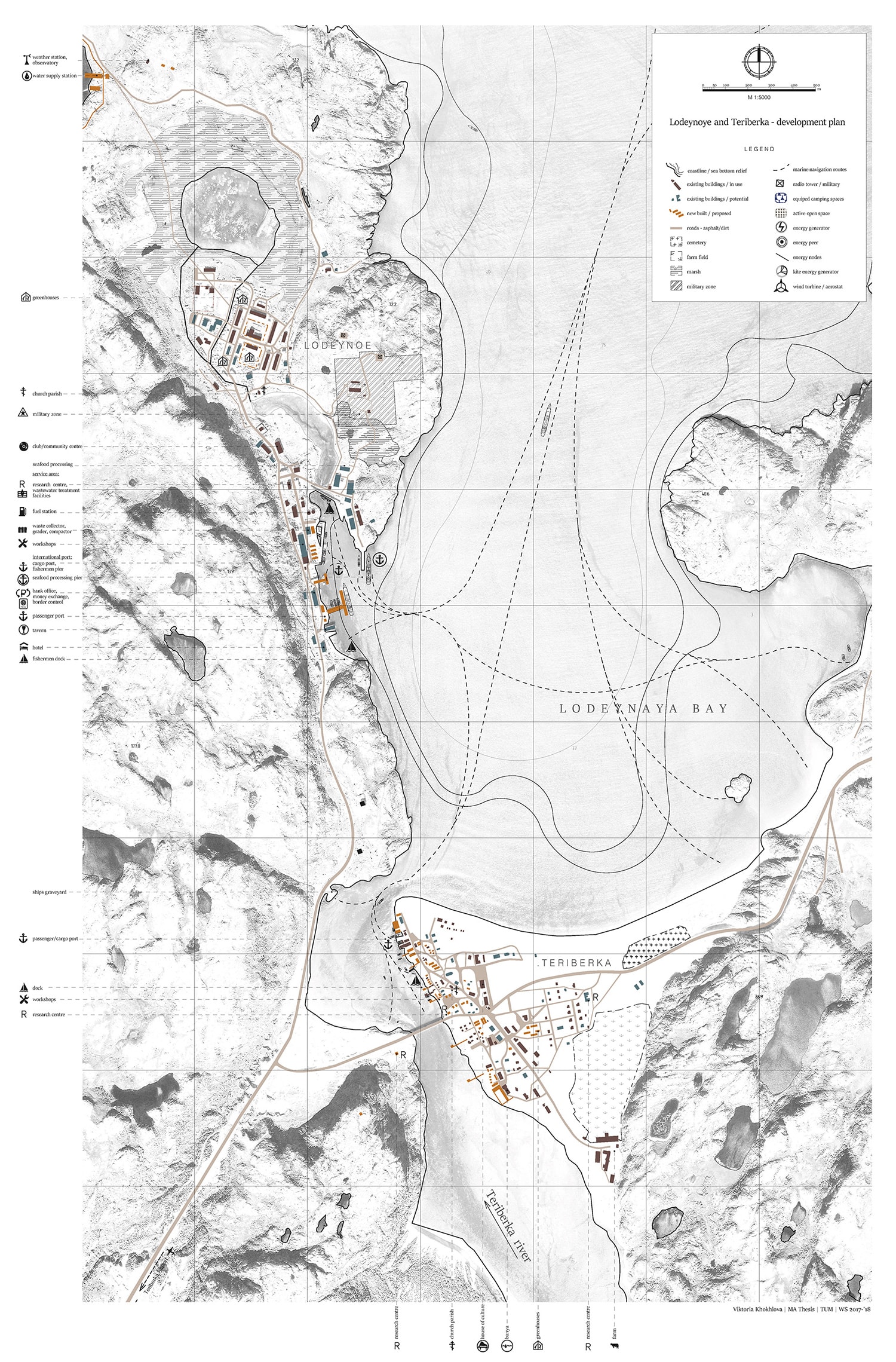

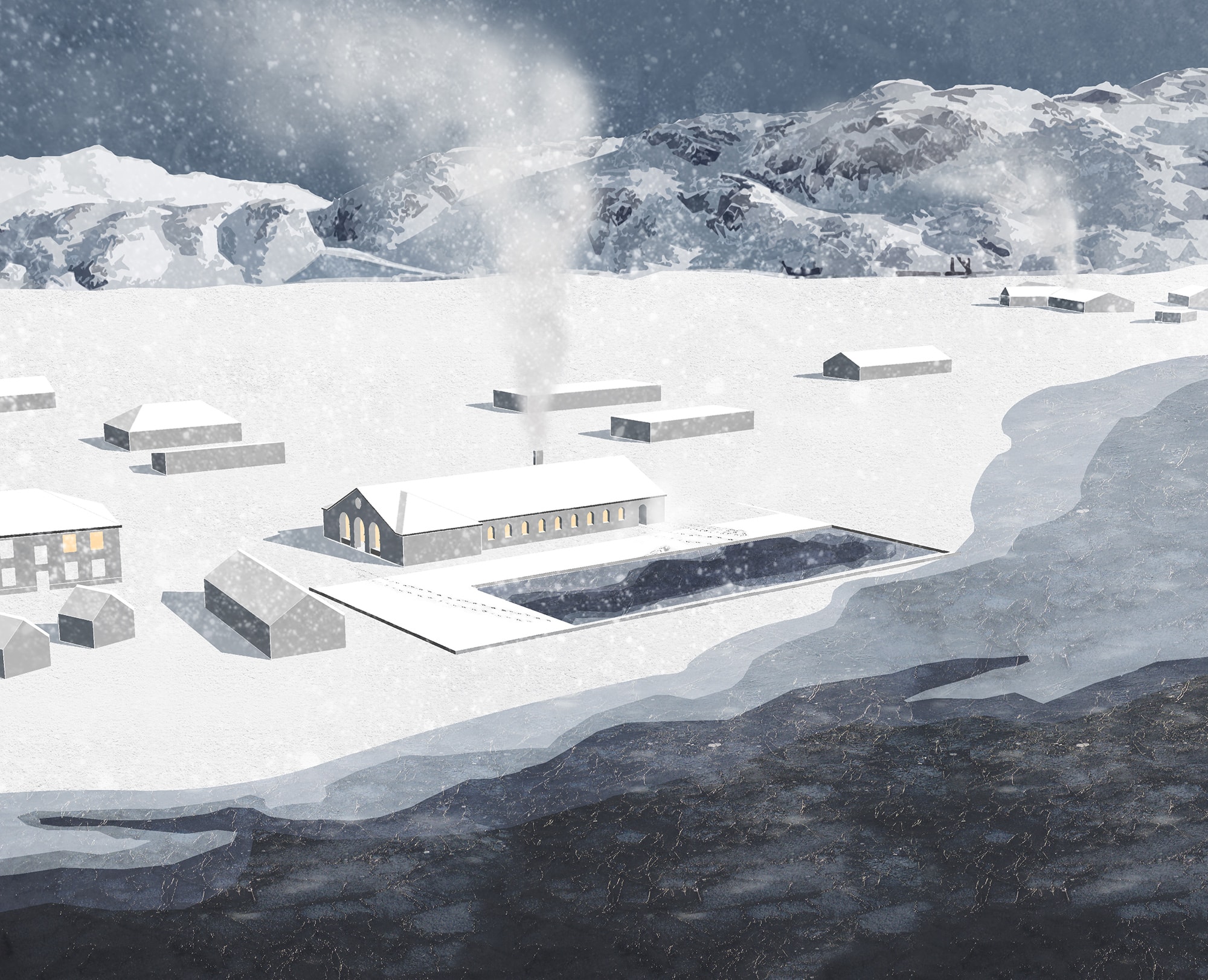

Is big always bad? What is the role of design in this typically technocratic space of engineering and policy? Dutch designers Maartin Hager and Dirk Sijmons present a scaling up of the energy imaginary, expanding the scale and efficacy with which design research typically operates, with their speculative vision for a massive expansion of carbon-free energy production in the North Sea. Mike Smith, meanwhile, takes us to the Arctic, to Alaska and the extraction territory of the oil-rich North Slope and its contested values. What might an alternative vision to endless extraction in the ecologically sensitive landscape be, and how might it be used to reshape the boom-bust nature typical of fossil energy extraction? Victoria Khokhlova visits another part of the Arctic in her speculative design project which imagines the emancipatory potential of renewable energy for remote outposts in the far North.

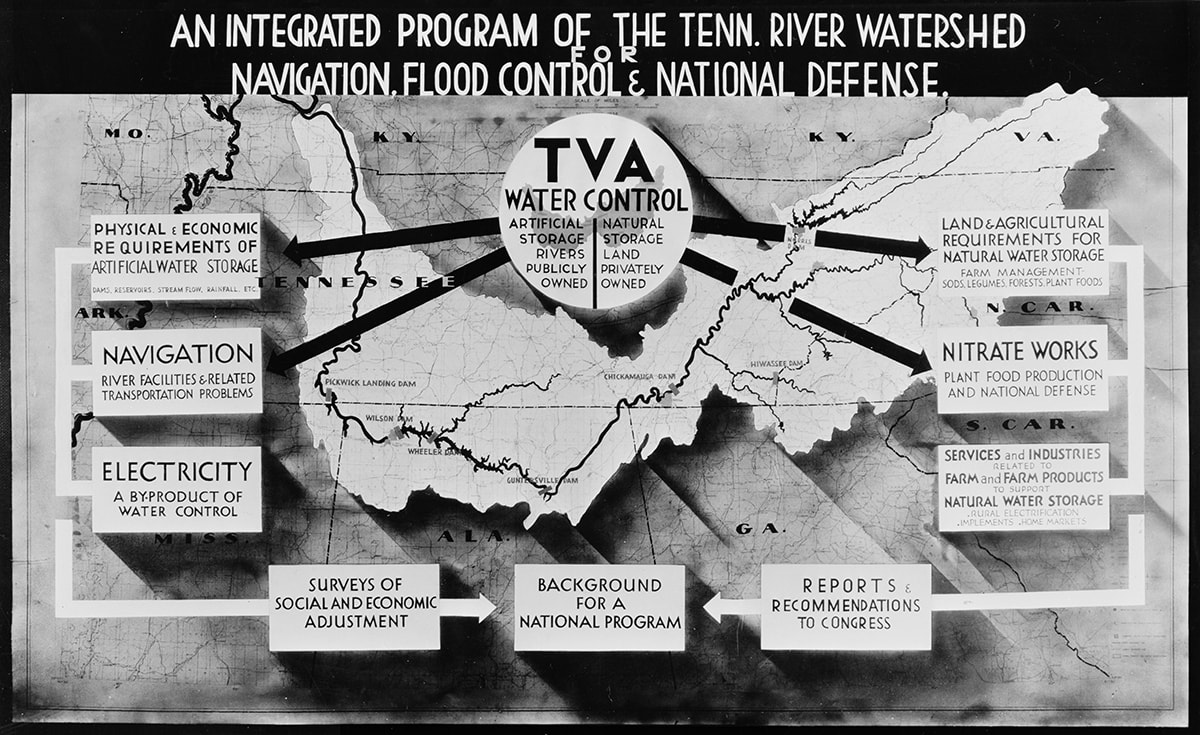

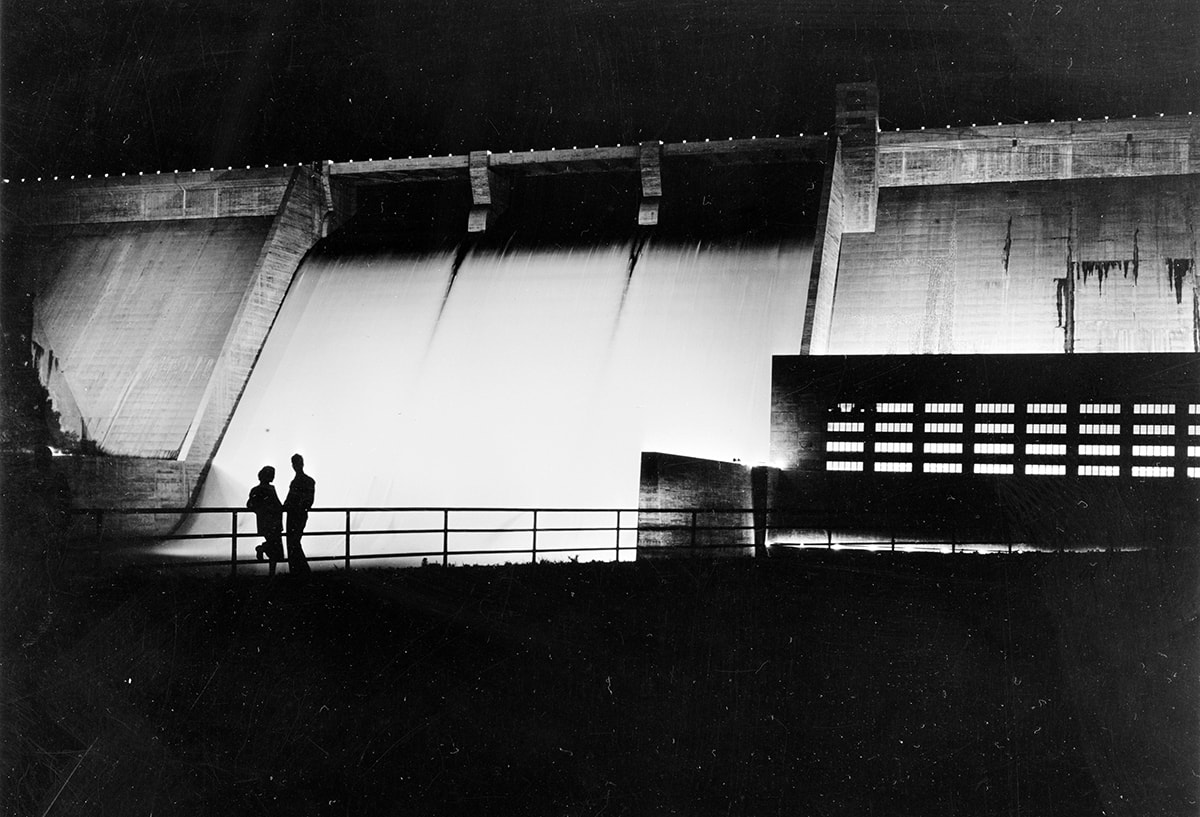

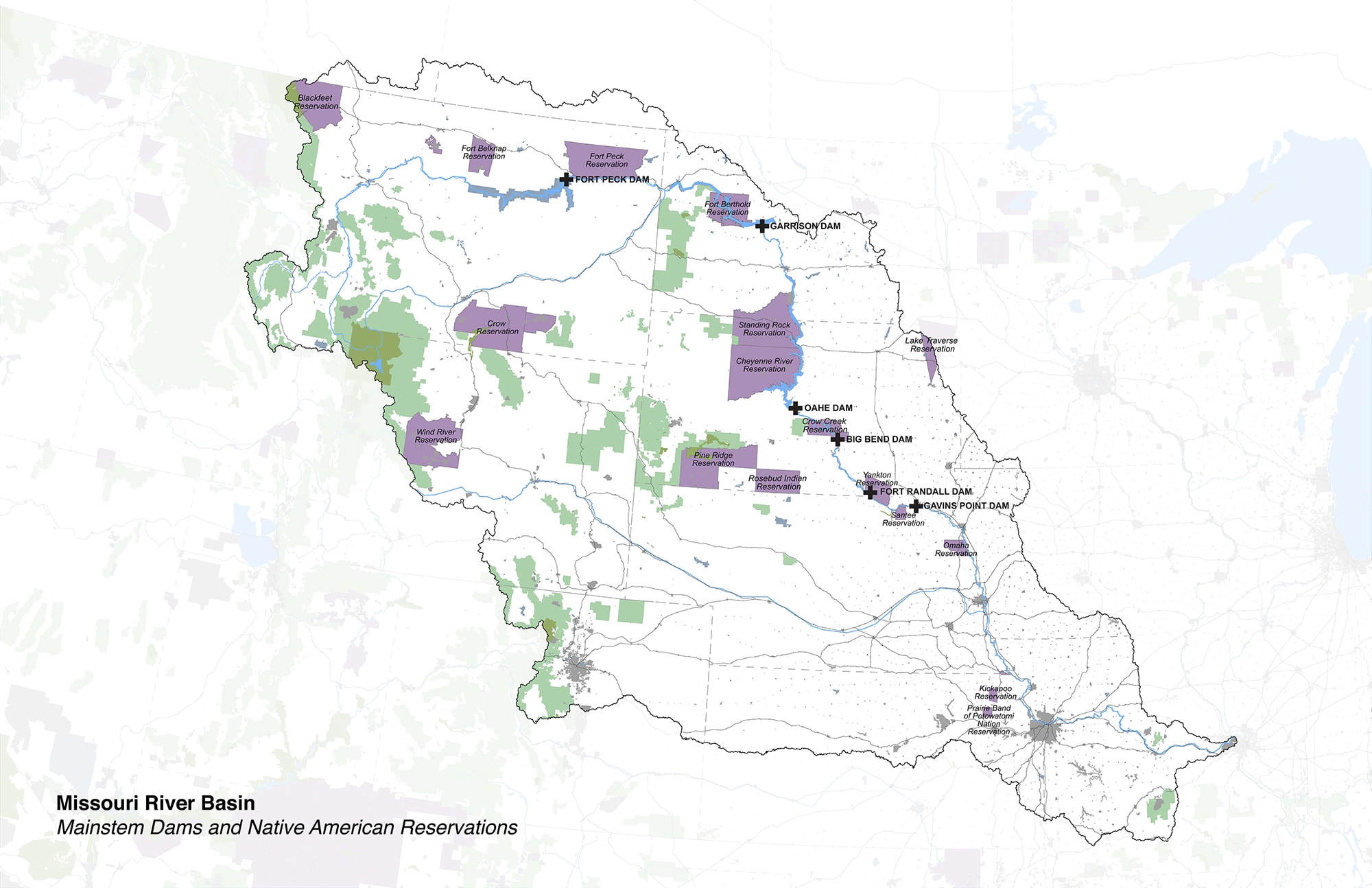

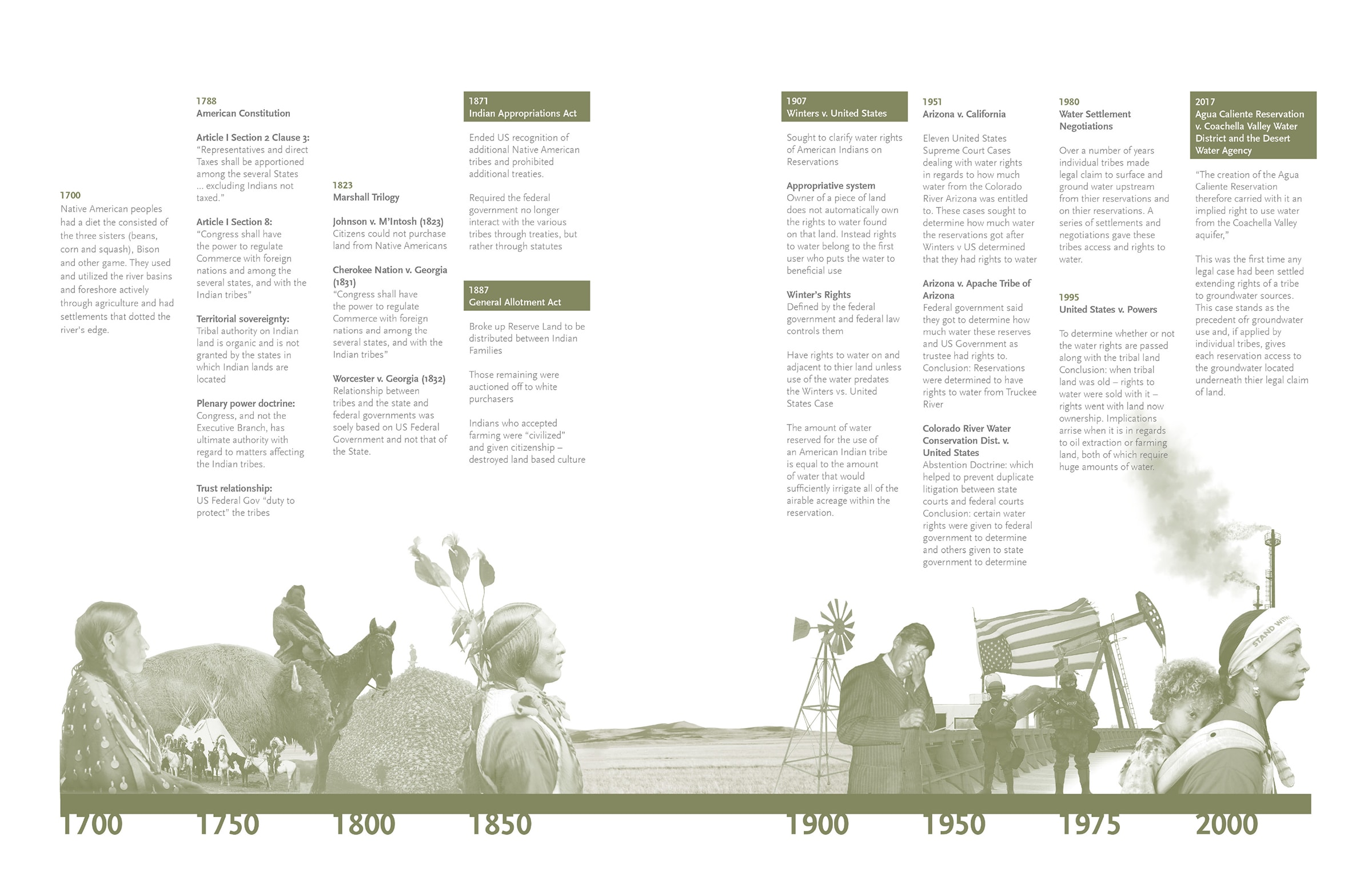

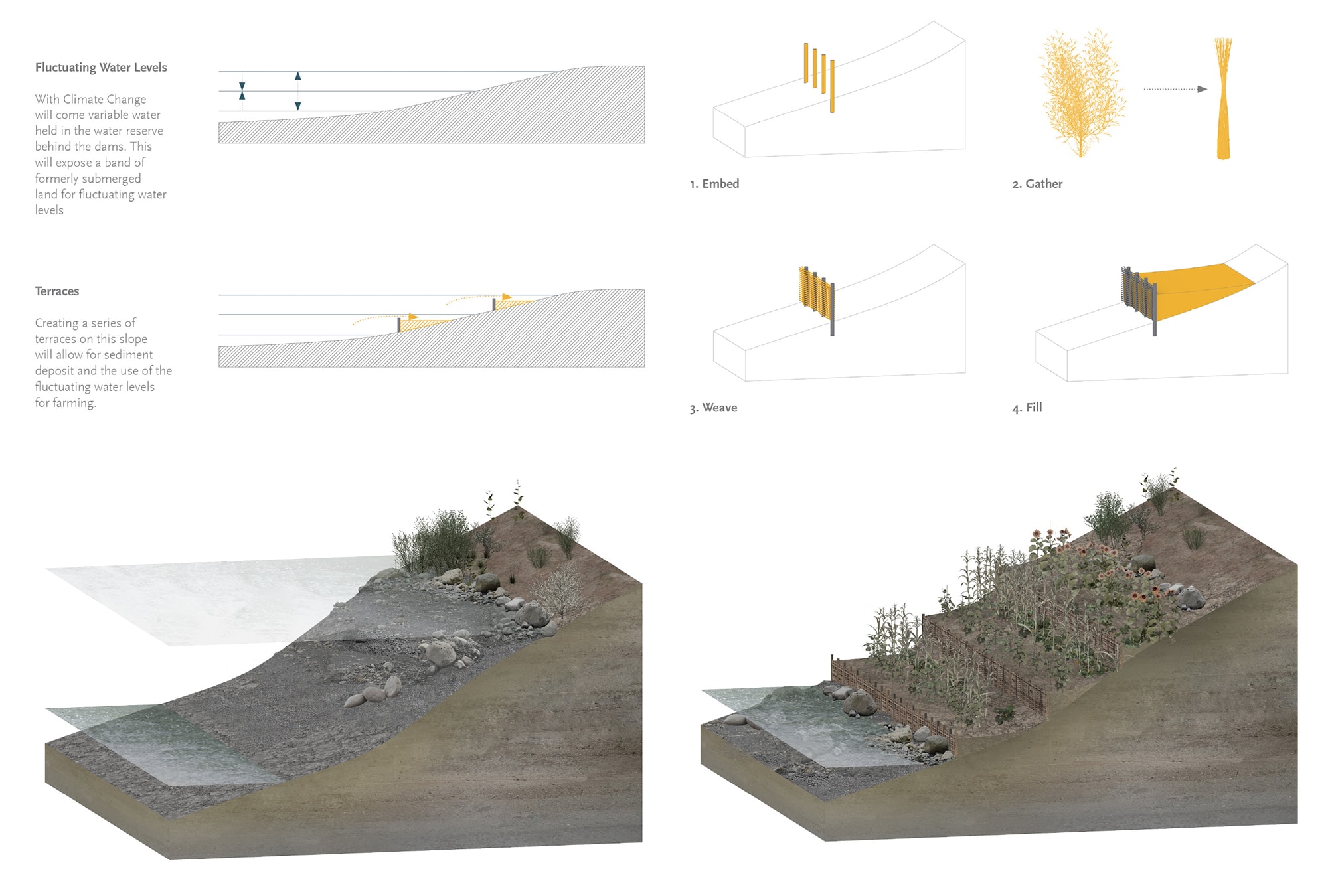

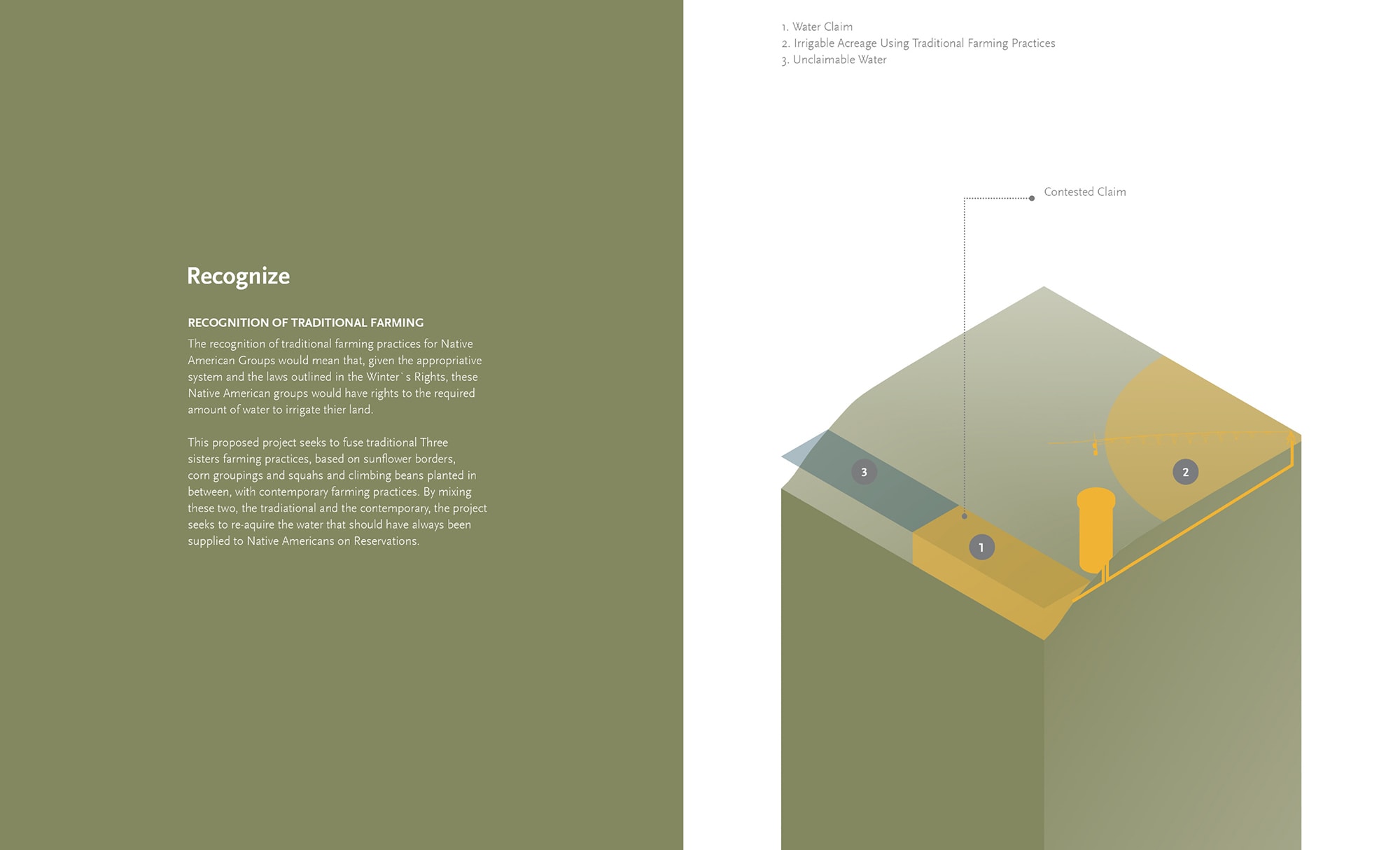

Not all power infrastructure is physical, or even visible. Power can be territorial, and also immaterial. The construction of territory is an act of power projection, but systems of consumption depend on the soft buying power offered by credit and capital. In this issue, Micah Rutenberg traces the parallel immaterial systems of power that the Tennessee Valley Authority developed alongside its system of dams, both the political power that allowed it to operate across the vast landscape of its seven-state region, and the systems of finance and representation that let it grow a brand-new culture of electricity use. But large dam projects carry some heavy baggage, specifically in their histories of displacing local populations — and in North America the burden of dam construction have fallen especially hard on Native American communities. In our issue, Kees Lokman looks at the oft-ignored colonial legacies of some of these major pieces of physical energy infrastructure, such as those that helped structure the modern American Midwest through extensive networks of dams. And his essay calls attention to the urgent need to foreground the colonial agenda that continues to pervade contemporary energy infrastructure projects—specifically the pipeline projects that cut through indigenous land and perpetuate environmental injustice.

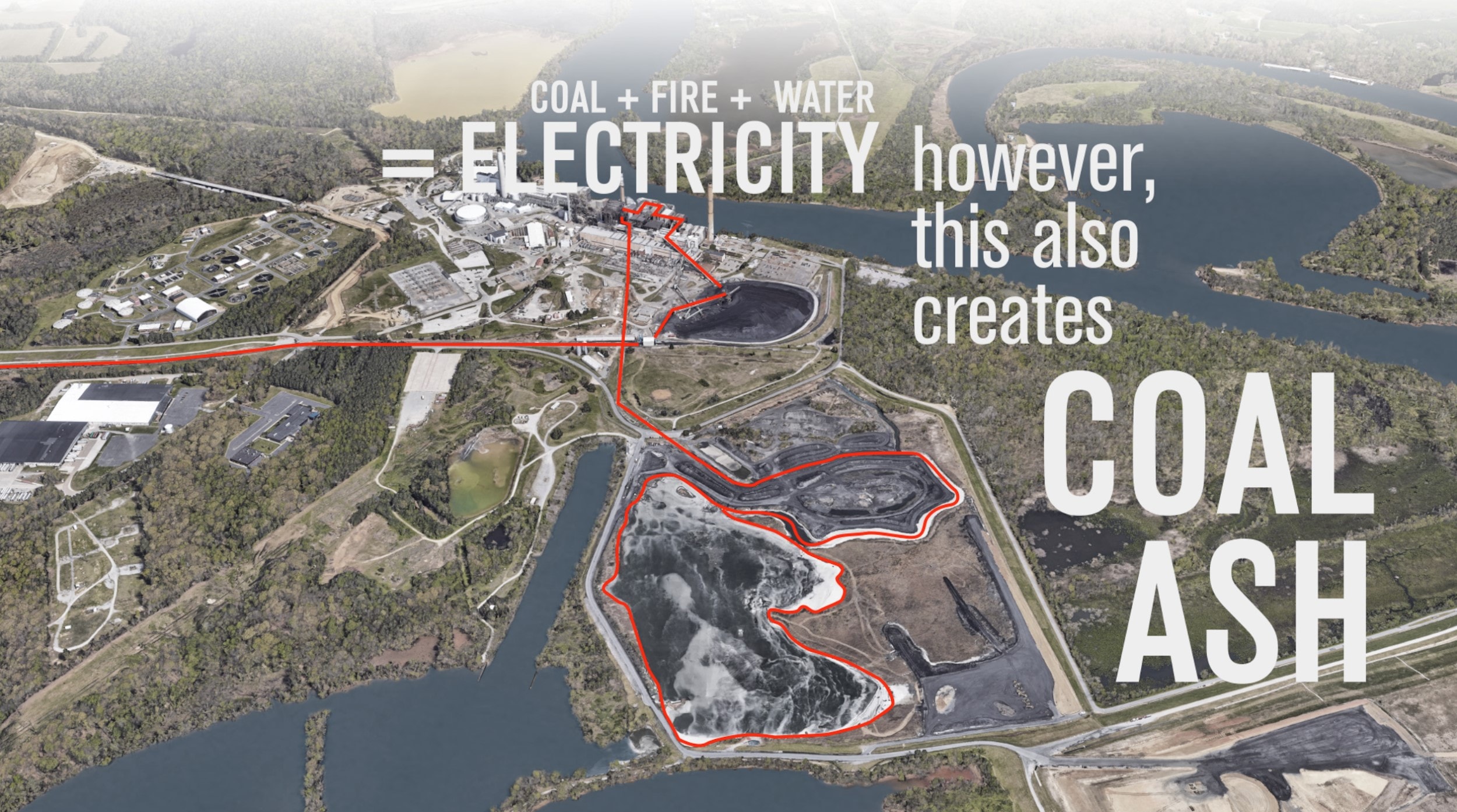

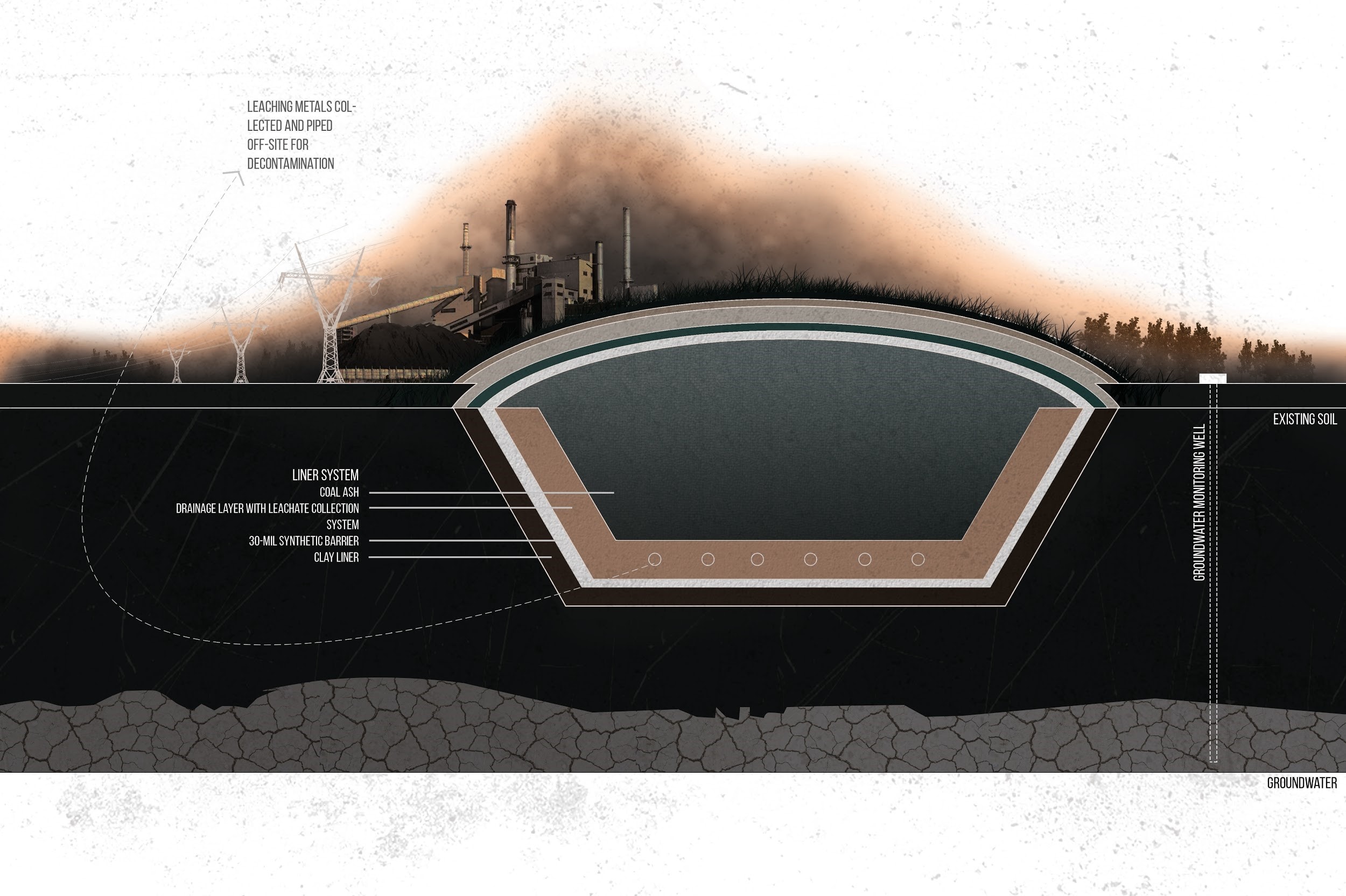

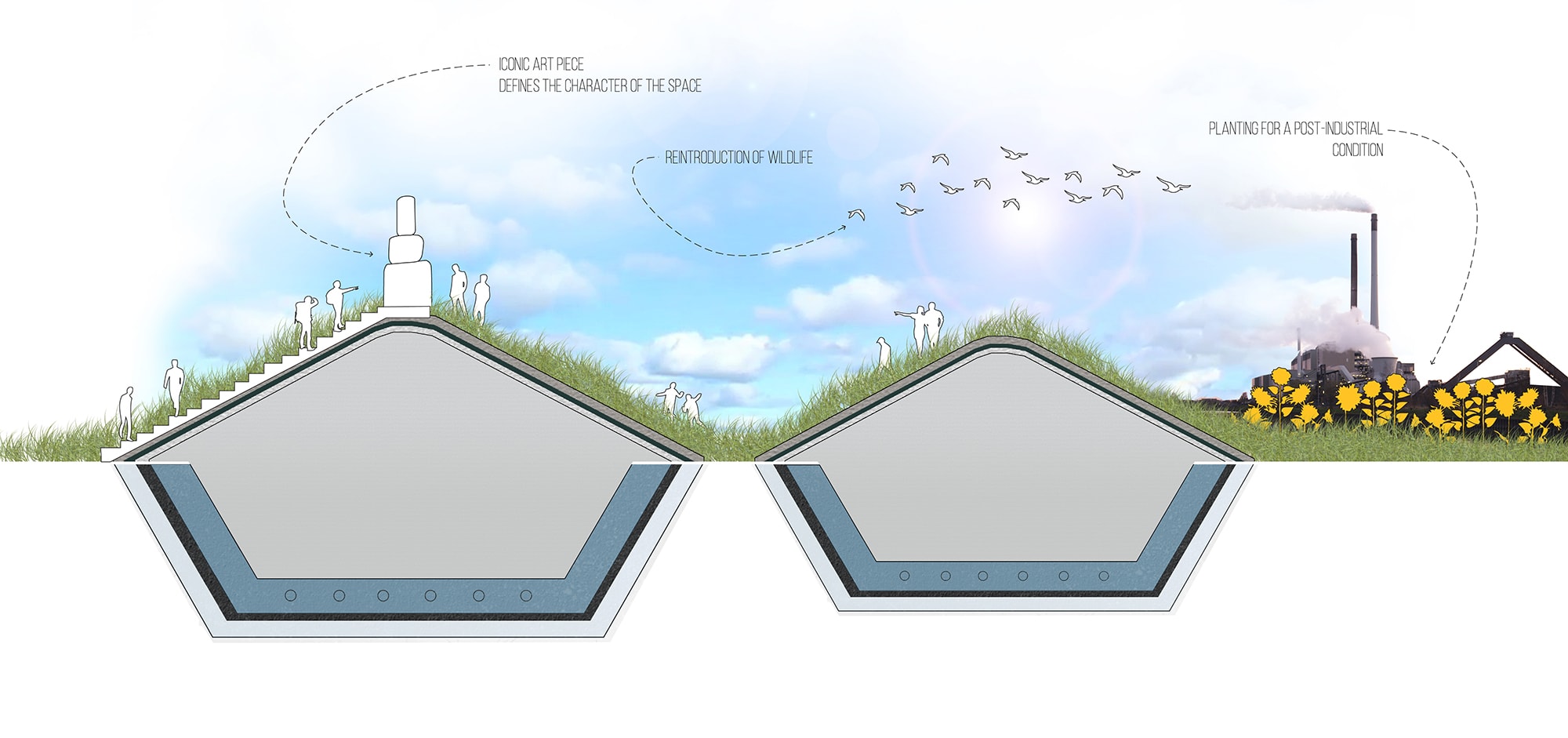

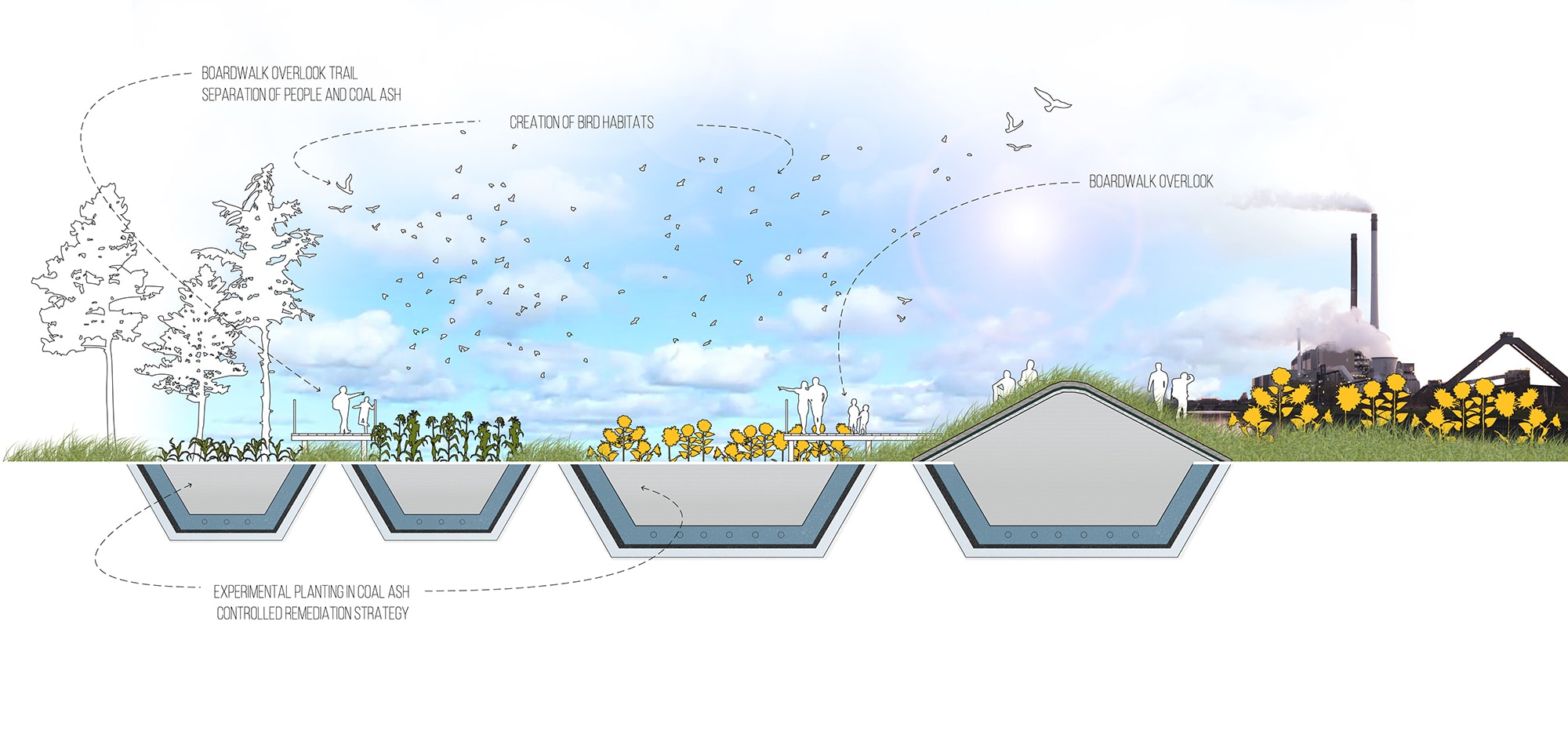

Then there are the pollution legacies of energy production — not just the extraction landscapes but also the byproducts of extraction. Lauren Delbridge highlights the risk that coal ash ponds present, continuing the toxic legacy of coal power, even as we transition away from coal energy.

But sometimes the waste landscapes of one industry can create the most compelling and benign inputs for a whole new infrastructure. Catherine De Almeida rethinks the definition of waste in Iceland, looking at how the waste landscape of geothermal energy were creatively repurposed to build the world-famous Blue Lagoon spa and resort.

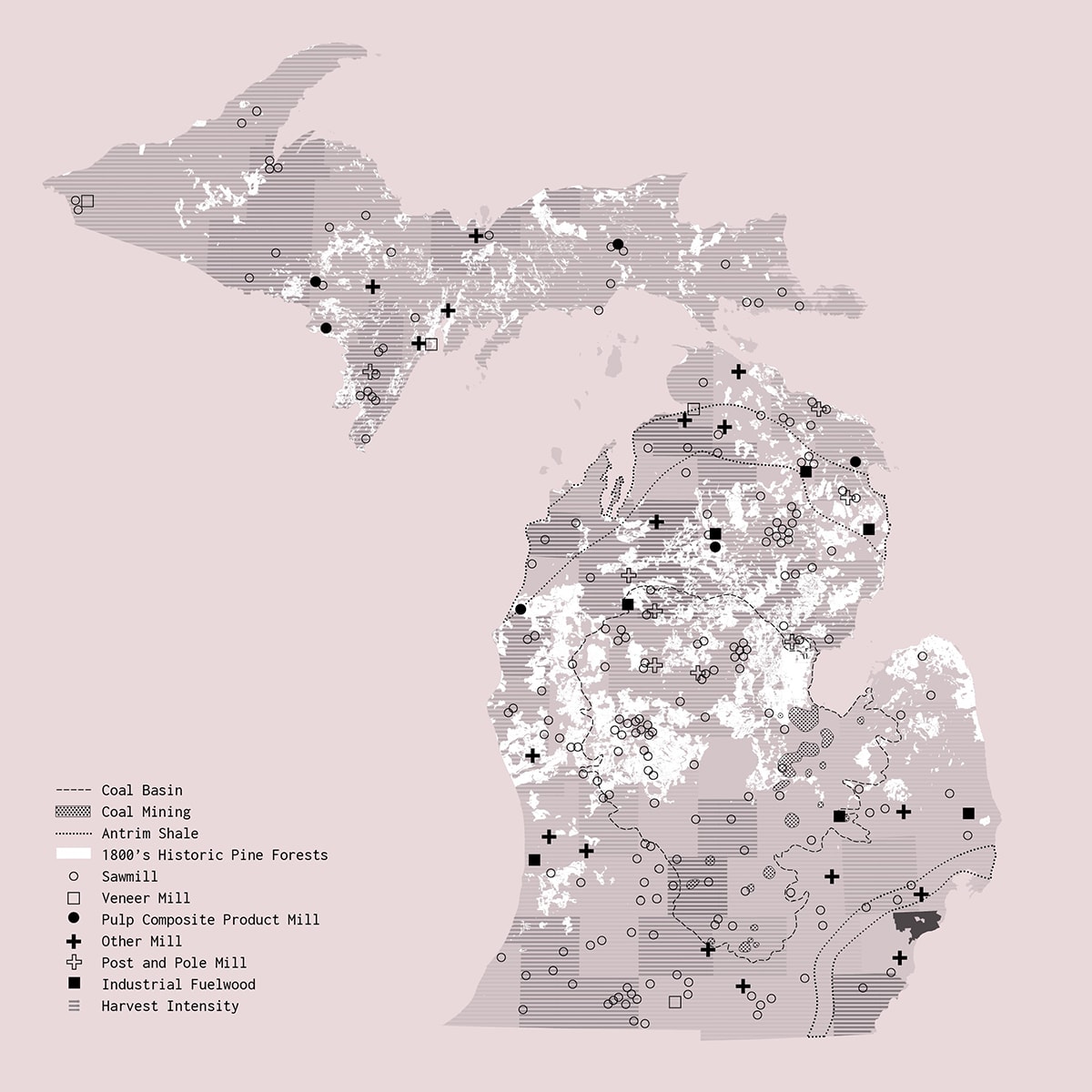

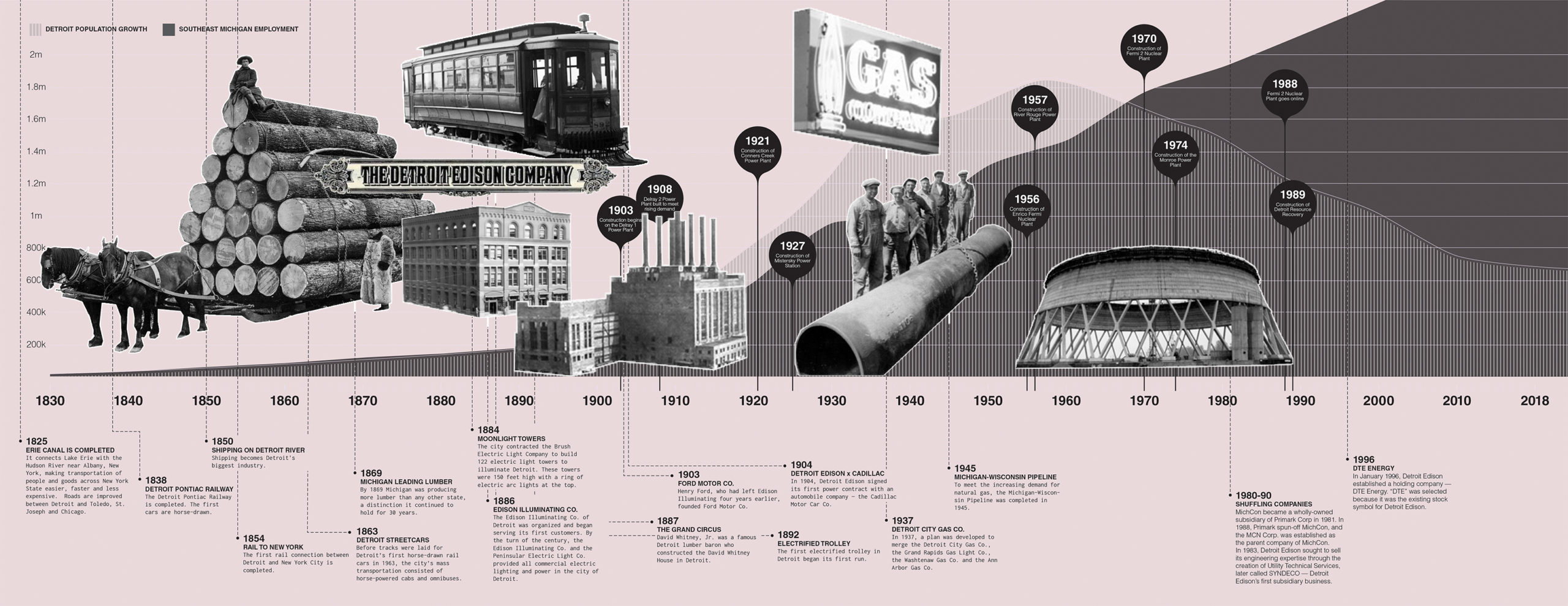

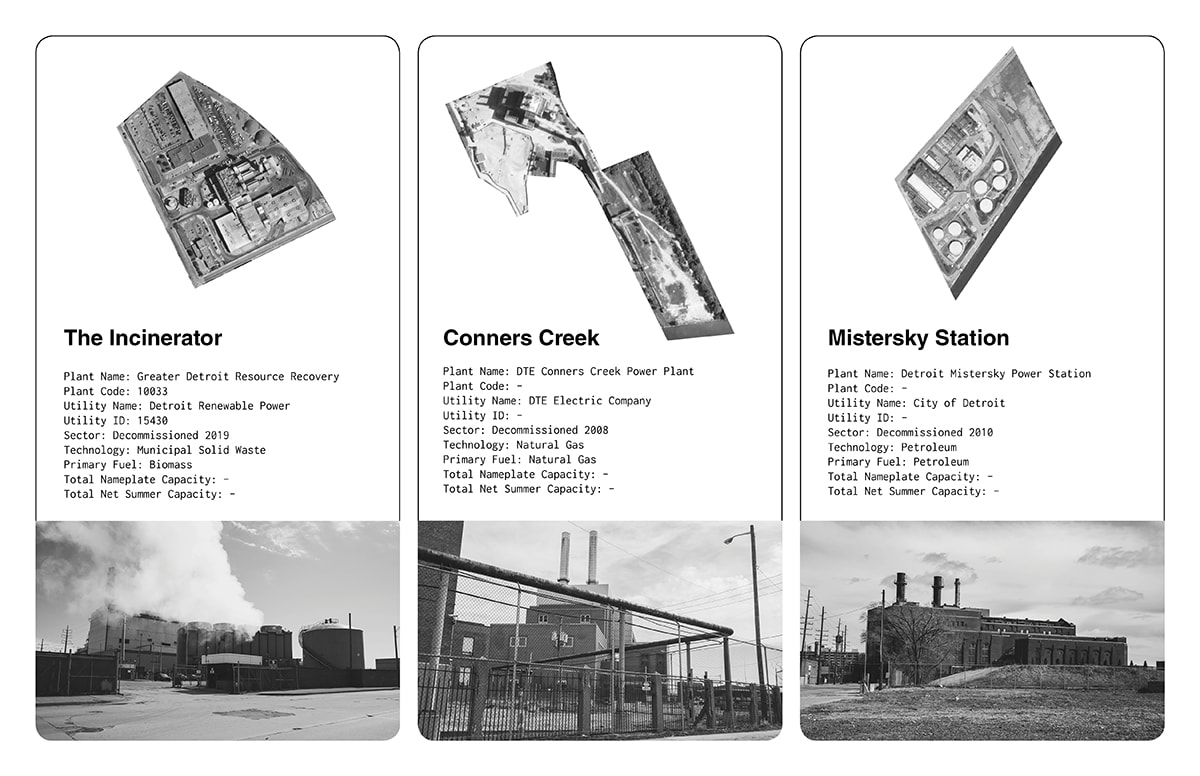

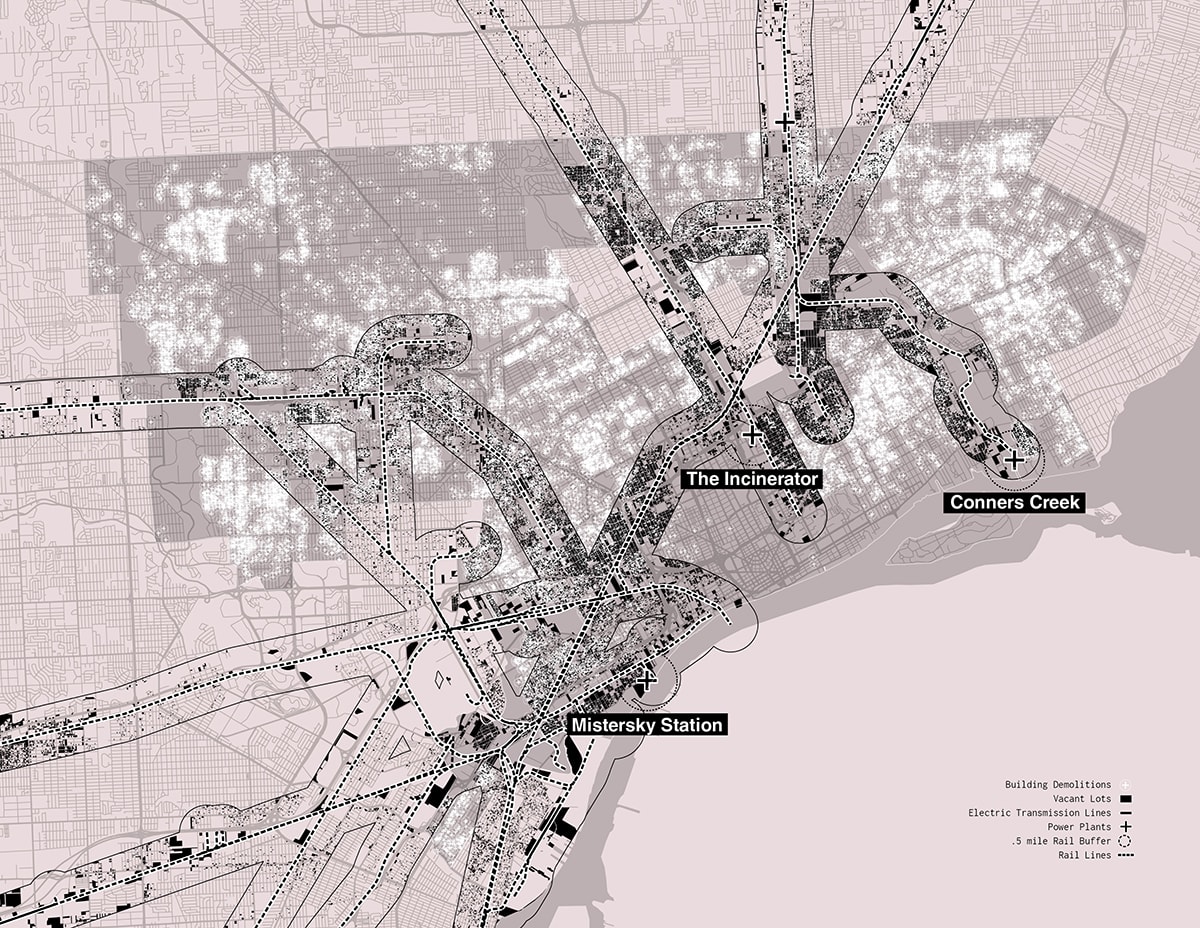

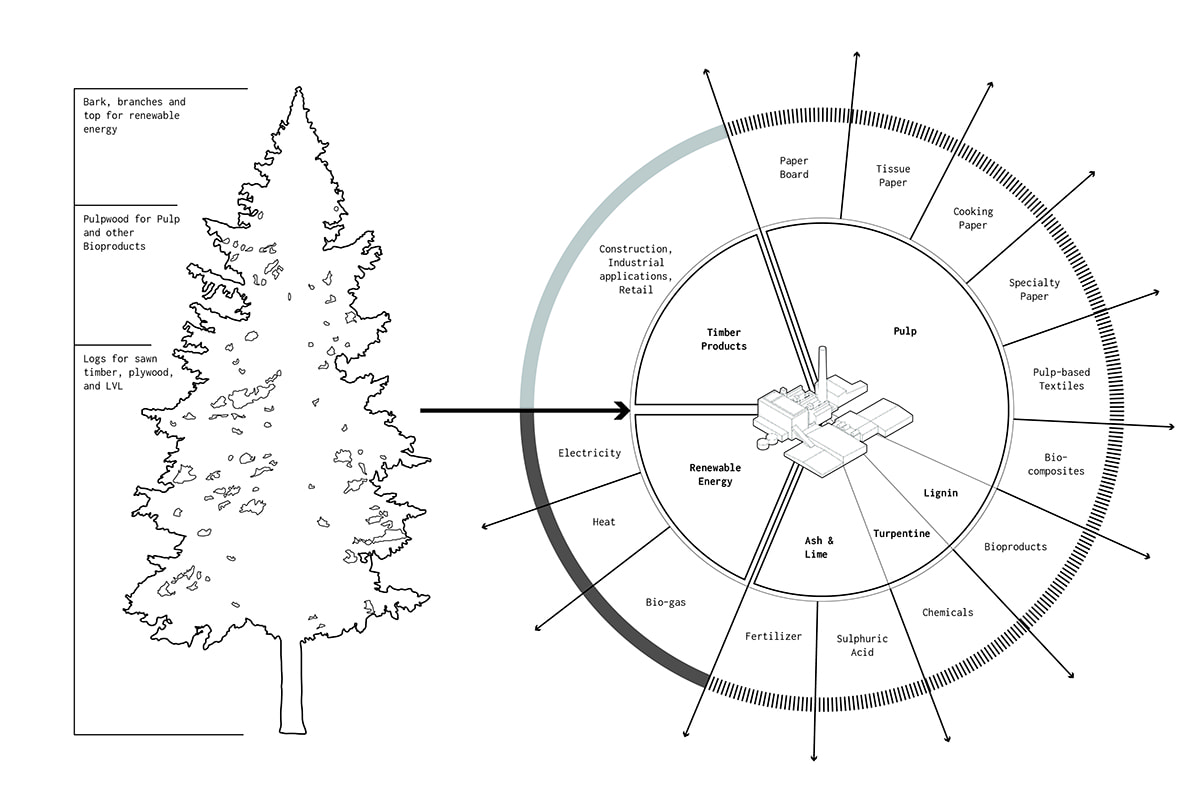

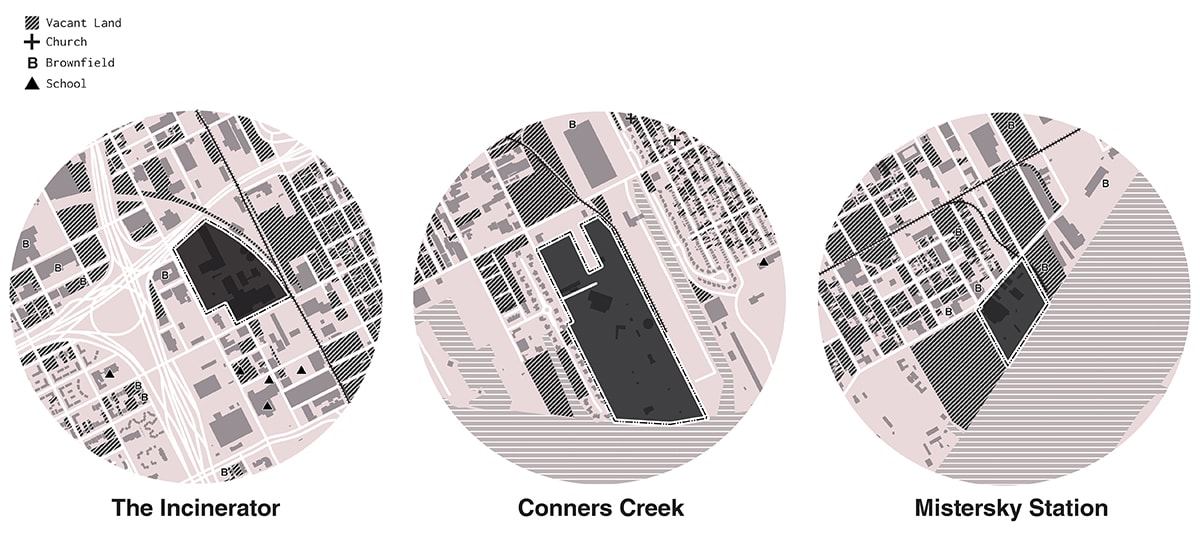

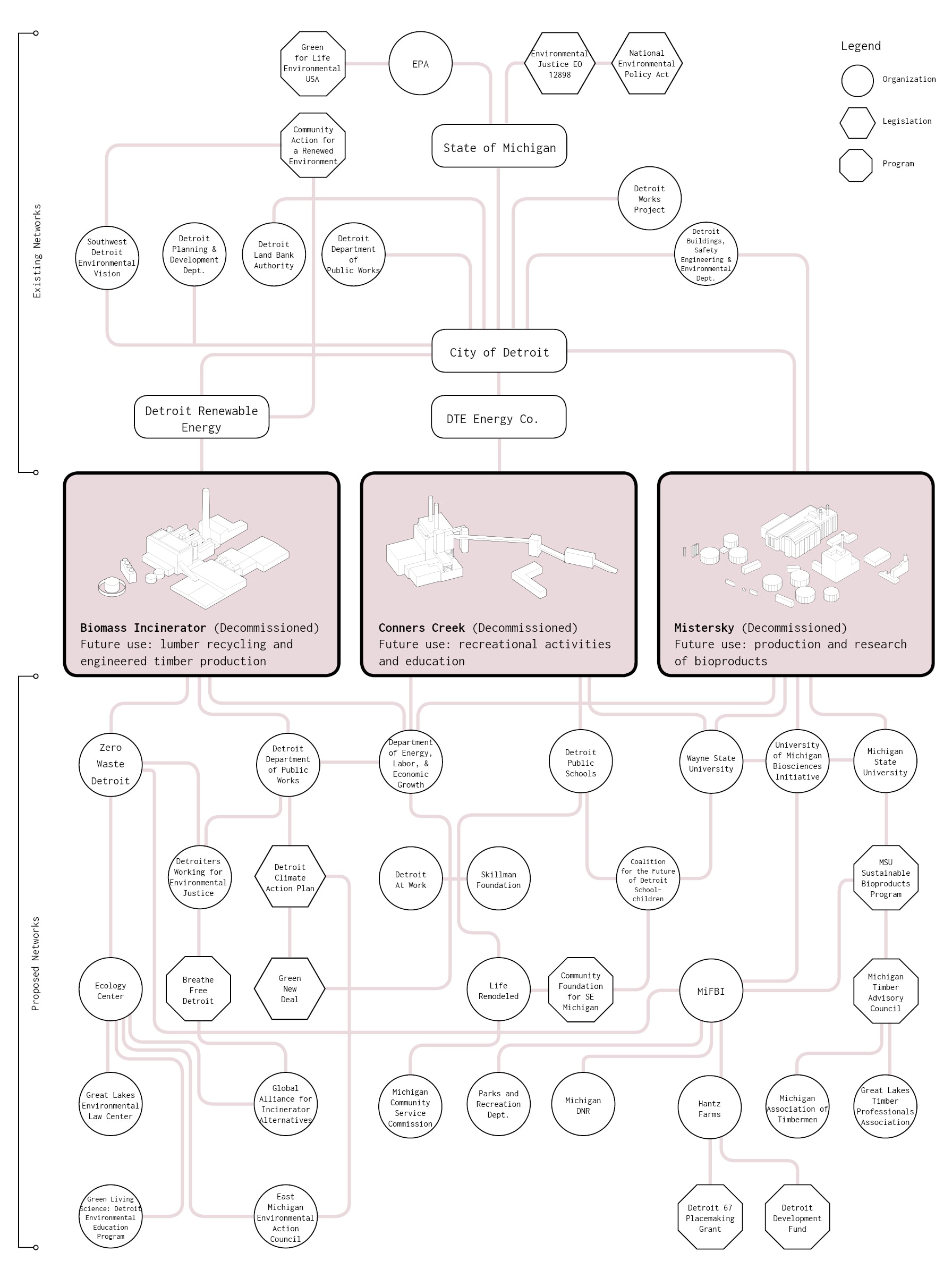

Julie Marin, Charlotte Timmers, and Bruno De Meulder rethink another kind of waste, considering biomass energy as part of a closed-loop renewable energy system, expanded to include the public space of the city. Salvador Lindquist and Eric Minton also speculate on a new energy system that utilizes biomass waste, and reimagine the possibilities of transforming the old and abandoned power plants of Detroit into newly vibrant centers of community and sustainable industry.

The design community, of course, has its own issues with power, inclusivity, and equity. Janette Kim uses board games to expose the ways in which power is wielded during participatory public design processes, literally designing the politics of compromise, coalition-building and collaboration. If designers hope to participate in this conversation, we need to actively address our own problematic relationship to power.

In it Together game play at the Higher Ground Leadership Workforce, an after-school program based at the Madison Park Academy Elementary School. Image: Janette Kim/Urban Works Agency.

Energy transitions proceed unevenly across the landscape, radically transforming some places while bypassing others. The effects on communities are similarly uneven: energy development typically exacerbates variation in the degrees of access to economic opportunity, to decision-making, and exposure to environmental harm. New renewable energy technologies could similarly produce unequal effects. How can a radical reimagining of energy infrastructure create opportunities for an inclusive and participatory conversation about climate change and social justice? Who has the power to talk about infrastructure, and who gets left out?

We hope that this issue shines a light on some of these topics in the context of the urgent transformations that must happen across every level and sector of society during this critical, transitional decade.

Acknowledgments

This issue was made possible in part by the support of the Kleinman Center for Energy Policy at the University of Pennsylvania. We would also like to express our heartfelt gratitude to all of the designers, activists and scholars who contributed work to this issue. Thank you to all of our friends and teachers in Puerto Rico who helped us better understand the intertwined topics of energy, power, and democracy on the island.

Nicholas Pevzner is a landscape architect, educator, theorist, and researcher working on the socio-spatial impact of energy infrastructure, including spatial planning for the renewable energy transition. He is a Senior Lecturer in landscape architecture at the University of Pennsylvania School of Design, and a Faculty Fellow at the Kleinman Center for Energy Policy at UPenn, with a decade of combined experience of teaching and working in landscape architecture. Nicholas teaches graduate design studios, which have included regional- and territorial-scale landscape design questions focused on landscape infrastructure and energy infrastructure. Most recently, he led a studio investigating the post-disaster response in Puerto Rico, which focused on strategies for advancing recovery in the wake of Hurricane Maria while promoting local community power. Central to this studio was the design and planning of multipurpose community facilities featuring resilient energy generation and critical services. Nicholas is the co-editor of Scenario Journal.

Stephanie Carlisle is a designer and environmental researcher whose work focuses on the relationship between the built and natural environment. She is a Principal at KieranTimberlake Architects. In addition to design practice, she also teaches courses on Urban Ecology, Embodied Carbon and Climate Change at the University of Pennsylvania School of Design. She is a co-editor of Scenario Journal.

Notes

[1] Hanna Breetz, Matto Mildenberger, and Leah Stokes. “The political logics of clean energy transitions.” Business and Politics 2018; 20(4): 492–522.

[2] Kacper Szulecki. “Conceptualizing energy democracy.” Environmental Politics 27, no. 1 (October 2017), https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09644016.2017.1387294

[3] Sean Sweeney, Kylie Benton-Connell, and Lara Skinner. “Power to the People. Toward democratic control of electricity generation.” Ithaca: The Worker Institute, Cornell University and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation, 2015.

[4] Florence Shulz. “What’s in the German coal commission’s final report?” EURACTIV Germany, January 28, 2019. https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy/news/whats-in-the-german-coal-commissions-final-report/

[5] Benjamin K. Sovacool and Michael H. Dworkin. Global Energy Justice: Problems, Principles, and Practices. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

[6] Raya Salter, Carmen G. Gonzalez, and Elizabeth Ann Kronk Warner, eds. Energy Justice: US and International Perspectives. Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2018. https://www.e-elgar.com/shop/eep/preview/book/isbn/9781786431769/

[7] Nick Estes. “Our History is the Future: Standing Rock Versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance.” London and Brooklyn: Verso, 2019

[8] Thea Riofrancos. “What Green Costs.” LOGIC Magazine 9, December 7, 2019. https://logicmag.io/nature/what-green-costs/.

[9] Gretchen Bakke. The Grid: The Fraying Wires Between Americans and Our Energy Future. New York and London: Bloomsbury, 2016.

[10] Jane Bennett. “Vibrant Matter.” Public Culture 17 (3), 2005.

[11] Today, the need for an expanded and modernized transmission system is well-recognized in virtually all well-respected national plans for deep decarbonization (ex: MacDonald, Clack et al., 2016; NERC’s 2019 Long-Term Reliability Assessment). A recent report from WIRES, a non-profit consortium of grid companies, lays out the need very clearly, stating that as more states, companies, and utilities commit to 100% carbon-free portfolios, “it is not possible to meet these goals without intraregional, and in some cases interregional, transmission connecting these resources to load.”

[12] Russel Gold. SUPERPOWER: One Man’s Quest to Transform American Energy. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2019.

Cite

Nicholas Pevzner and Stephanie Carlisle, “Introduction: Power,” Scenario Journal 07: Power, December 2019. https://scenariojournal.com/article/introduction-power/