Among the oldest of technologies, the extractive industries involve the removal and processing of raw materials from the earth and their global scale of operation has transformed entire regions and markets. The Lehigh Valley in southeastern Pennsylvania gave rise to several world-class extractive industries, including steel and cement production, coal mining, and slate quarrying, all of which would dominate the American and international scene by the first decade of the twentieth century.

As Sir Neil Cossons has keenly observed, “the world came of age in the twentieth century [;] a century endowed at its outset with immense industrial power, widespread prosperity, and emerging technologies that were to affect the lives of every person on the planet” [1]. The Lehigh Valley’s cement and slate industries were no exception, and their success created a much altered landscape with vast and deep quarries, enormous kilns, and mill buildings. These places, the intersection of geology, technology, and culture, were an important part of American life and their stories are still accessible through the visual testimony of the land, the structures, and the machinery, as well as the stories of those who last labored there. Many such sites, rich in historical value, are also environmental brownfields, making them doubly important as landscapes of remediation. They are part of a complex landscape that now demands consideration of its latent architectural, ecological, and socio-cultural assets.

Slate Quarry, Slatedale, PA, 2000. Photo by Joseph Elliott

2013 marked the 50th anniversary of Kenneth Hudson’s groundbreaking book and manifesto on “industrial archaeology,” the “mongrel” field he first named as the bastard offspring of industry and archaeology [2]. Today the remains of industry past dominate the global landscape. Urban and rural America are littered with the evidence of the last two centuries of the country’s former industrial prowess and many of these places, now abandoned, hold latent value for their transformation and reuse. Since Lawrence Halprin’s 1967 conversion of Ghirardelli Chocolate Company’s headquarters to public retail and Richard Haag’s 1971-1976 Gasland Park in Seattle, myriad other examples [3] in the U.S. have since followed. Recent initiatives such as the Industrial Heritage Reuse Project by the Preservation League of New York State are specifically examining the reuse potential of several abandoned industrial buildings in Albany to provide model approaches in similar urban contexts elsewhere. But many other less adaptable sites such as brick yards, cement plants, and quarries of landscape scale, pose enormous difficulties for preservation and reuse.

Despite the recent popularity of industrial chic, critics now question whether this form of “adhocism” — that is, the improvisation of new, unrelated uses devoid of meaning and interpretation — has led to, at best, a polite taming of industrial heritage, and, at worst, its grotesque disfigurement in the name of gentrification and short-sighted corporate marketing. A shift in thinking is now required for more sustainable preservation: thematic approaches that examine the problems and potential based on the original industrial processes; consideration and interventions at the landscape scale, ecological as well as architectural thinking, and finally, human connections through past and current associations.

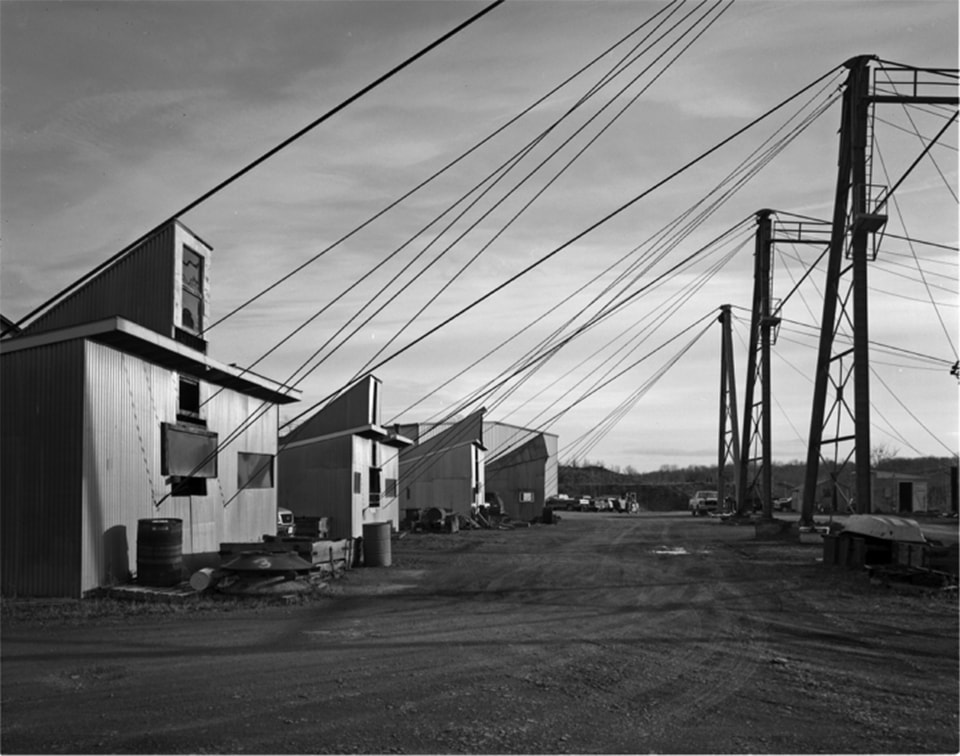

Slate Hoists, Penn Argyl PA, 2010. Photo by Joseph Elliott

Slate World

The Pennsylvania “Slate Belt,” an area of only 22 square miles, lies approximately 50 miles to the northwest of Philadelphia and just south of Blue (Kittanning) Mountain between the Delaware and Lehigh Rivers. The first quarries opened in the 1830s, but significant growth followed in the first decade of the twentieth century when Lehigh Valley accounted for approximately half the slate produced in the United States, eventually becoming the greatest slate producing region in the world [4]. During World War I, many of the slate firms closed to release men for other essential war work, especially in the Bethlehem Steel plant nearby. Most of the quarries never reopened after the war as modern synthetic materials such as asphalt composites and plastics proved less expensive and easier to use, and required less skilled labor to fabricate and install.

American Bangor Slate Quarry, 2015. Photo by Preston Hull

Penn Big Bed Slate Hoist Masts, 2015. Photo by Preston Hull

Today only a handful of the old slate quarries remain active. Big Bed Slate, still in operation, is one of the oldest and best preserved of the early operations with its iron crane hoists, steam and electric machinery and mill shops, and extensive series of former and active quarries. This company, still economically viable, and interested in spearheading a reinterpretation of the valley’s industrial history, offers a unique opportunity together with the Slate Belt Heritage Center in Bangor, PA to document that legacy through a creative mix of preservation and economic development.

Hercules Cement Company, 2015. Photo by Preston Hull

Cement Age

Reinforced concrete would prove to be the modern material of the new century and in the United States, the creation of the first Portland cement plants in the Lehigh Valley in 1871 at Coplay, would give rise to an industry that would forever change the face of America and the world [5]. An essential component of concrete, Portland cement is second only to water as the most consumed material on the planet. By 1901, the Atlas Portland Cement Co. in Northampton, PA was the largest cement company in the United States – more than twice the size and probably five to ten times the size of most firms in the industry. Cement consumption increased almost ten-fold from 1890 to 1913 and until 1907, more than half of the Portland cement produced in the United States came from the Lehigh Valley. Today the valley is still the country’s center of cement production but automation has rendered the old plants nearly vacant, their historic mills and kilns, though still impressive, largely abandoned.

National Portland Cement, 2015. Photo by Preston Hull

Ranger Lake (former Lehigh Portland Cement quarry), Ormrod, PA 2014.

Photo by Joseph Elliott

Industrial Archaeology

Why invest in preserving these former industrial landscapes? The industrial legacy of Pennsylvania’s cement and slate belt holds the key to revitalization of the region by “regeneration through heritage,” not only in the preservation and possible re-use of these sites, but as catalysts for reviving and maintaining the social and cultural fabric of their surrounding communities and reclamation of the natural environment. First, their continued physical existence is critical to understand how the region took shape physically, socially, economically, and culturally, more than any text or photograph can convey: real structures in real landscapes. Second, these early twentieth century sites extend the region and country’s industrial narrative from the classic eighteenth and nineteenth century notion of industrial heritage to those complexes that were responsible for America’s emergence as the world power by the latter twentieth century. Third, although the twentieth century is better documented than any other century in word and image, analog and digital, the industrial artifact and place, where they survive together, still remain the primary locus for analysis and interpretation. Cultural and environmental conservation become powerful partners in reclaiming this complex place through ecological and social, as well as architectural and technological concerns. By taking a cultural landscape approach to the analysis and redevelopment of these overlapping industries, we acknowledge their original premise of natural resource extraction and exploitation in the deconstruction and re-construction of the land.

LafargeHolcim (Whitehall), 2015. Photo by Preston Hull

Alpha Cement Silos, 2015. Photo by Preston Hull

Lafarge Cement, (former Whitehall Cement Co.), Cementon PA, 2014.

Photo by Joseph Elliott

Research for this essay comes from a recently launched PennPraxis project at the University of Pennsylvania, School of Design, focused on the extractive industries. It is funded by the J. M. Kaplan Fund and directed by Frank Matero, Professor of Architecture and Historic Preservation, and aims to bring a more critical approach to the identification, evaluation, and preservation of the most important and neglected of American industrial sites. Acknowledgements to Joseph Elliott, Preston Hull and Amy Lambert for their contributions.

Frank G. Matero is Professor of Architecture and former Chair of the Graduate Program in Historic Preservation at the School of Design at the University of Pennsylvania. He is Director and founder of the Architectural Conservation Laboratory and a member of the Graduate Group in the Department of Art History and Research Associate of the University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. He was previously on faculty at the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation of Columbia University and guest lecturer at the International Center for the Study of Preservation and the Restoration of Cultural Property (ICCROM) in Rome, as well as lecturer at the Polytechnic University of Puerto Rico. He received his graduate degrees in architecture at Columbia University and in conservation at the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. He is a Professional Associate of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works and former Co-chair of the Research and Technical Studies Group and on editorial boards of The Getty Conservation Institute, the Journal of Architectural Conservation, and Cultural Resource Management. Currently he is editor-in-chief of Change Over Time, a new international journal on conservation and the built environment published by Penn Press.

Frank G. Matero is Professor of Architecture and former Chair of the Graduate Program in Historic Preservation at the School of Design at the University of Pennsylvania. He is Director and founder of the Architectural Conservation Laboratory and a member of the Graduate Group in the Department of Art History and Research Associate of the University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. He was previously on faculty at the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation of Columbia University and guest lecturer at the International Center for the Study of Preservation and the Restoration of Cultural Property (ICCROM) in Rome, as well as lecturer at the Polytechnic University of Puerto Rico. He received his graduate degrees in architecture at Columbia University and in conservation at the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. He is a Professional Associate of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works and former Co-chair of the Research and Technical Studies Group and on editorial boards of The Getty Conservation Institute, the Journal of Architectural Conservation, and Cultural Resource Management. Currently he is editor-in-chief of Change Over Time, a new international journal on conservation and the built environment published by Penn Press.

Notes:

[1] Stratton, M. and B. Trinder 2000. Twentieth Century Industrial Archaeology. New York: E & FN Spon, vii.

[2] Hudson, K. 1963. Industrial Archaeology: An Introduction. London: J.Baker.

[3] These examples of conversion were driven in part by building booms in the 1970s and 80s, as well as by historic rehabilitation tax credits stemming from the Tax Reform Act of 1976.

[4] Dale, N. 1914. Slate in the United States. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

[5] Lesley, R. 1924. History of the Portland Cement Industry in the United States. Chicago: International Trade Press.