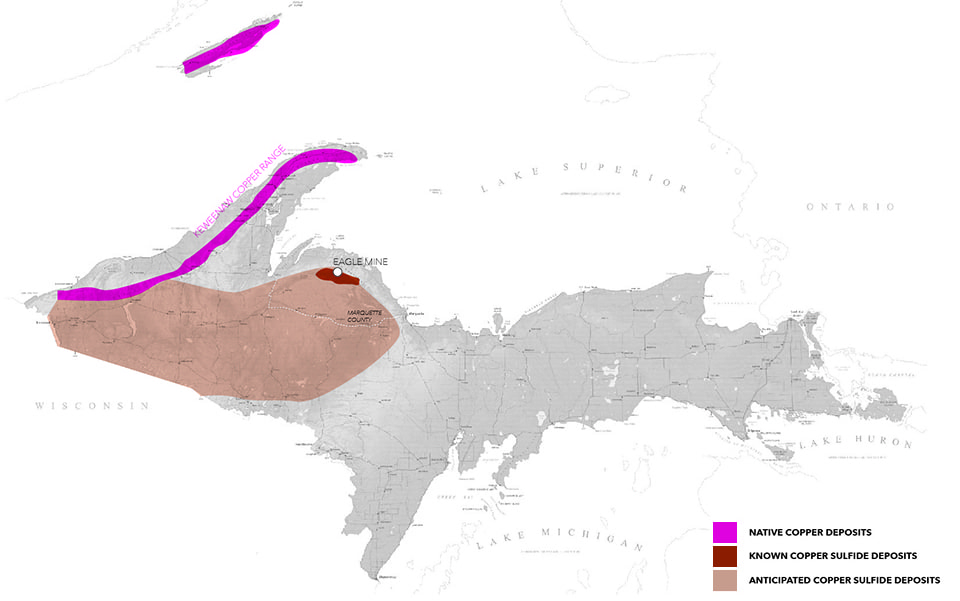

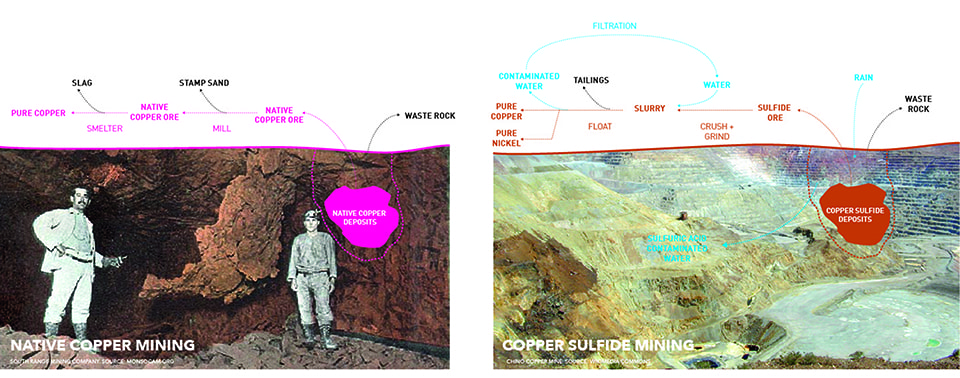

In 2002, transnational mining company Kennecott Minerals discovered a rich body of copper sulfide ore below the forests of Marquette County, near the shores of Lake Superior. Although the region has a strong history of copper mining, new and proposed mines in Marquette County harvest toxic copper sulfide instead of the native (pure) copper of the Keweenaw range [1]. In spite of the fact that the Keweenaw Peninsula has the world’s largest deposit of native copper, and that copper mining was the region’s main economic driver for over a hundred years, the copper mining industry largely left Michigan’s Upper Peninsula in the mid-twentieth century when the mines were no longer profitable. However, the discovery of an accessible copper sulfide lode in Marquette county in 2002, combined with rising copper prices, has led to a return of copper mining interests to the region. When the Kennecott Minerals Company requested to lease mineral rights for the construction of Eagle Mine from Michigan’s Department of Natural Resources (DNR) in 2007, a number of groups stepped forward to contest this landscape claim. This essay delves into the politics of this dispute and explores ways in which the concerns of each group are tied to a view of nature, natural resources and appropriate use of the landscape.

The introduction of copper sulfide mining ignited fierce public debate over landscape value and appropriate use of public land in Marquette County. In 2008 the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community (KBIC), which claims Eagle Rock as a sacred site, launched three state and local cases against Kennecott questioning the legality of their mining permits.

Upper Peninsula of Michigan [top];

Upper Peninsula of Michigan Copper Deposits [bottom].

Map Data: Google [top]; bottom image by Elizabeth Yarina

The KBIC was joined in the lawsuit by a diverse group of local organizations, each with their own perspective on landscape value. For the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community, the narrative is one of heritage, where cultural values are closely tied to the elements of earth, water, plants, and animals. The Yellow Dog Watershed Preserve (YDWP) claims landscape value through narratives of biodiversity, hydrology. For the exclusive members of the Huron Mountain Club, “untouched wilderness” serves as an exclusive mark of status and as a luxury commodity. While anti-mining groups may operationalize, value, or describe aspects of the landscape in different ways, opposition to the Eagle Mine aligns groups who otherwise have little common ground to stand on. These strange bedfellows brought the case all the way to a federal appeals court before ultimately failing to stop the construction of the mine.

In Depoliticized Environments, Erik Swyngedouw argues that in the era of the Anthropocene, Nature has become de-politicized, with decisions about land management falling largely “outside the field of public dispute, contestation, and disagreement” [2]. In this work, Swyngedouw calls instead for a re-politicization of nature that allows for complex conversations about contemporary ecological threats. In the case of Eagle Mine, such a debate has been made public through lawsuits and public discourse, allowing a depiction of nature that isn’t reduced to a single-dimensional object for consumption or preservation. Instead landscape is represented through a diverse collection of voices, becoming a richly conceived “object of concern” [3].

Copper Processing: Native Copper Vs. Copper Sulfide. (Image by Elizabeth Yarina)

A Continuously Modified Landscape

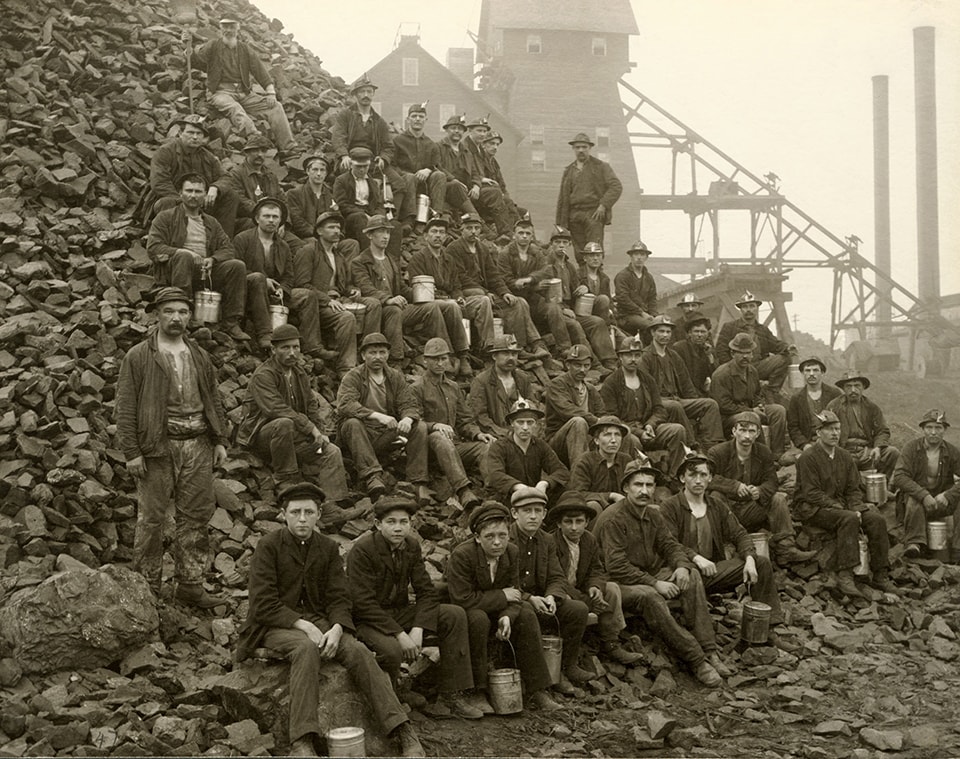

The Keweenaw Peninsula has the world’s largest deposit of native copper—a rare naturally occurring pure mineral form compared to the copper sulfide and copper oxide deposits found in most other copper mining districts—and the area became a major commercial producer of copper in the 1840s. The depth of its fissures and its incredibly large veins, however, make the extraction of Keweenaw’s native copper a laborious process, requiring it to be chiseled out of the surrounding rock and broken down into manageably-sized pieces.

Prior to the arrival of European settlers, the Michigan’s Keweenaw copper lode was mined by Native Americans as early as 5,000 BC, and its copper was found across the continent as a trade good in the form of jewelry, tools, and decorative objects [4]. It was through Ojibwe legends that word of Michigan copper reached the first explorers and missionaries to the region. Broad and shallow Native American pit mines later became the first successful mining sites for entrepreneurial settlers [5].

These early settlers saw the landscape as one to be tamed and consumed. Henry Schoolcraft, who called the Upper Peninsula the “ends of the earth,” was in 1921 the first to recommend large-scale exploration of copper deposits, leading to the division of the land by the US government into 9 square mile (and eventually 1 square mile) parcel units for mining activities. The land was ceded to the United States as part of an 1842 treaty with the Ojibwe tribe. With the land now bound and divided, early miners began clearing forests and blasting surface deposits, leading to the 1844 Copper Boom.

Tamarack Copper Mine, Tamarack, Michigan. (Photo courtesy of Keweenaw National Historic Park Archives)

Early manipulations of the landscape in the name of mining included the dredging of Portage Canal, laying of railroads and highways, logging for building and fuel, construction of company-built housing and schools, and the building of mines and smelters [6]. Despite the fact that the Keweenaw copper lode is highly pure native copper, it still must be separated from attached hard or molten rock, producing stamp sands and slag. These stamp sands remain highly visible in the landscape of the Keweenaw today, resisting re-vegetation due to high concentrations of heavy metals, which continue to be dangerous to human and animal health. The built relics of the mining boom also continue to define the region’s landscape, alternately hailed as historical cultural landmarks or attacked as dangerous and toxic ruins [7].

Mining is not the only force that has shaped the landscape. While the Upper Peninsula is 80% forested, it is very much a curated and managed landscape. Logging is a major industry and outdoor sports are important to recreation and tourism. In the Michigan Northwoods, everything from forest composition to deer population is regulated by economics and policy.

The Keweenaw Waterway and Michigan Smelter near Houghton/Hancock Michigan (between 1900-1906) [top]; Quincy Mining Company Stamp Mills Historic District, Houghton County, MI [bottom].

(Photos by Detroit Publishing Co. [top]; Andrew Jameson [bottom])

Recognizing the many varieties of landscape manipulation, calls into question any clear definition of ‘nature.’ The natural landscape of the Upper Peninsula is not simply the “5-Star Wilderness” that the state’s tourism board markets, but rather a complex “product of civilization” [8]. The notion of an uninhabited wilderness also ignores centuries of Native American heritage and landscape modification. These ideas demonstrate the inherent contradictions in ideas of wilderness. Instead of viewing the Upper Peninsula as a fetishized uninhabited wilderness, understanding the role of the landscape as part of broader human history, culture and economics allows us to reintroduce ourselves into discourse on the landscape of the Copper Country.

Whose Land and Whose Copper?: Actors and Their Claims

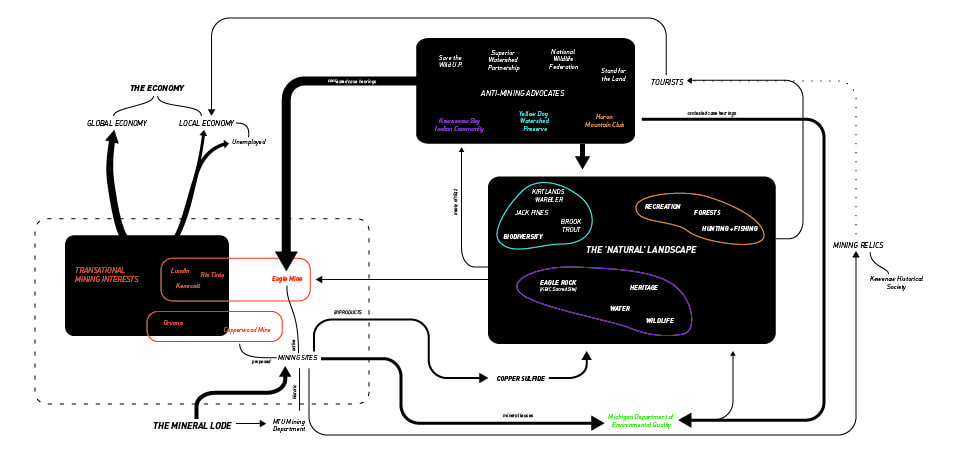

In the case of Eagle Mine, a diverse set of actors continuously manufacture their own narratives of nature and resource values. Through acts of collective storytelling, each group stake claims to overlapping layers of landscape. Although dozens of interests have been involved in the opposition or approval of Eagle Mine, here we will examine the five key players that each have a unique take on the value of the Upper Peninsula landscape.

Actor-Network: The five key actors explored form complex relationships with landscape objects, economies, and mining sites.

“Landscape as Commodity”

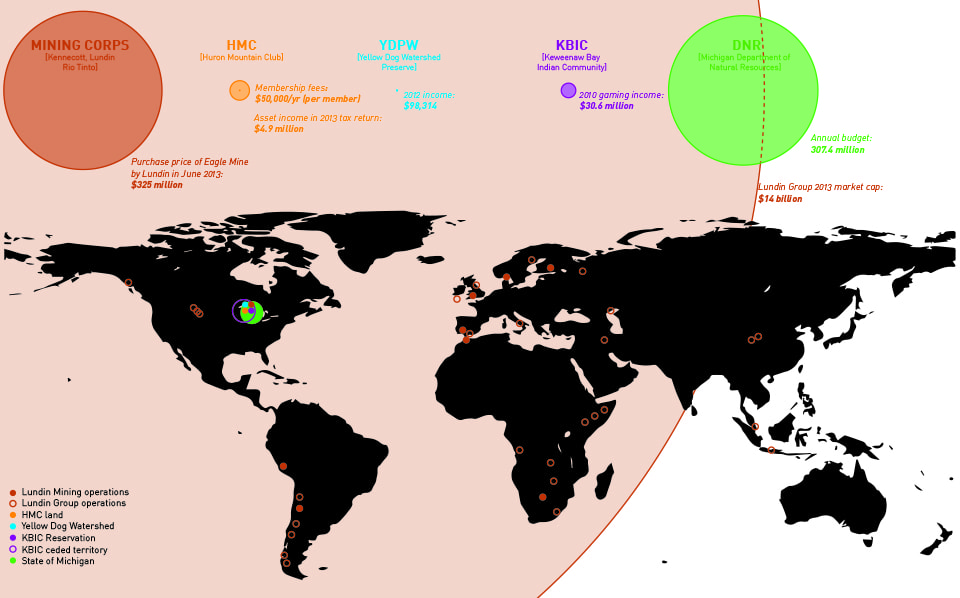

Eagle Mine has changed hands three times in its short history, so the corporations of Kennecott, Rio Tinto, and Lundin are termed here as ‘mining interests.’ The current owner, Lundin Mining Corporation, is Swiss-owned and operates in Europe, Africa, South America, and North America [9]. Lundin Mining is just one branch of the Lundin Group, a $14 billion dollar mineral extraction conglomerate. The title of their 2013 operations map sums up the company’s ethos as a “continuous worldwide quest for overlooked opportunities”.

Lundin’s representations of the Eagle Mine project make clear where the value lies for them: in the “high quality and low cost copper” that will be “accretive to Lundin Mining shareholders” [10]. Promotional images highlight the conversion of forested landscape into extraction landscapes and subterranean representations of geological deposits appear as though this commodity is simply floating in empty space, waiting to be harvested [11].

Lundin Facilities at Eagle Mine. (Image courtesy of Jeremiah Eagle Eye)

“Landscape as Heritage”

One of the most powerful voices opposing the legality of Kennecott’s mining permits has been the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community (KBIC), based 15 miles to the west of Eagle Mine, on the largest and oldest Native American reservation in Michigan. Eagle Mine occupies a small part of what used to be expansive Ojibwa Indian territory, spanning Western Upper Michigan and Northern Wisconsin, which was ceded in the Treaty of La Pointe on October 4, 1842. Treaty provisions included fishing and hunting rights, detailing guarantees of special access by tribal members to fish and wildlife within the ceded region [12].

The KBIC tribal council remains attentive to ecological issues within the larger ceded territory through their Natural Resources Department, citing concern for ecosystem damage and toxic drainage into ground and surface water systems. They have “identified mining as a priority concern due to its potential to significantly impact treaty rights, treaty reserved resources, area ecosystems, and the health and welfare of the community and future generations” [13]. Through the heritage of this ceded territory, the KBIC makes claims to the “natural resources” of the Upper Peninsula, for “subsistence, spiritual, cultural, management, and recreational purposes.” For the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community, the narrative is one of heritage, where cultural values are closely tied to the elements of earth, water, plants, and animals.

More dramatically, the sulfide lode extends below a rocky forested outcrop called Eagle Rock (Migi Zii Wa Sin), which the KBIC claims as a sacred site, culturally and spiritually important to the Ojibwa. It is a place where vision quests, fasting events, and other ceremonies are still held. The entrance to the Eagle Mine is bored right under Eagle Rock, and fences have been erected around the outcrop. Although Eagle Rock is on public land, the mining interests have attempted to deny access through the terms of their Mineral Lease [14]. Through the leveraging of local police enforcement, claims to the land by the Ojibwe are seemingly superseded by the mining interests’ ability to manipulate power.

These claims ultimately led to a two contested cases and one lawsuit against to the State of Michigan opposing the Eagle Mine beginning in 2007 alongside other local groups. When these cases proved unsuccessful, the KBIC in 2014 petitioned the UN for the State of Michigan’s infractions against the 1842 treaty through their approval of mining operations on traditional Ojibwa territory.

Protest at Eagle Mine. (Photo by Yoopernewsman)

“Landscape as Status”

Joining The KBIC in the 2007 contested case against Eagle mine were the The Yellow Dog Watershed Preserve and the Huron Mountain Club (HMC) [15]. The HMC is unique amongst these as an elite, members-only organization.

The Huron Mountain Club is a 26,000 acre private hunting and fishing retreat founded in 1889. It has 150 members most of whom are wealthy families who reside in Chicago or metro Detroit. Access to club land is restricted to members and their guests, and its perimeters are actively patrolled. The HMC and its members are cloaked in secrecy [16]; however, the HMC does allow pre-approved scientific and educational groups to visit their land for academic purposes.

For the exclusive members of the Huron Mountain Club, whose high-end rural retreats share watersheds, air, and fish and game stocks with the Eagle Mine just three miles from their boundary, the ownership of “untouched wilderness” serves as an exclusive mark of status and as a luxury commodity. While in their contested case against Kennecott/Rio Tinto the HMC cites the ecological damage to the rare brook trout spawning habitats in this river, they also cite “irreparable damage to the value of club lands” [17]. For the HMC, landscape value is inherently bound to concerns of wealth and status.

Gene’s Barn, Big Bay, Michigan. (Photo by Save the Wild U.P.)

“Landscape as Ecosystem”

The Yellow Dog Watershed Preserve (YDWP) is an environmental organization and another plaintiff in the contested cases opposing the Eagle Mine. Eagle Mine is sited at the Northern Boundary of the Yellow Dog Watershed in the Yellow Dog Plains, a unique jack pine habitat home to the endangered Kirtland Warbler. The Yellow Dog River “runs free and clean through wild country until it eventually reaches Lake Superior” [18]. Protection of these water supplies and habitats are key to the YDWP’s mission.

Anti-sulfide mining advocacy has grown as one of the YDWP’s focus areas, and besides their political action against the mines through court cases, they also have been monitoring the river’s quality since 2010. One major criticism of copper sulfide mining is the danger of leaching toxic sulfuric acid and heavy metals into groundwater. Through their discussion of water supply, the YDPW’s ecology-centric values are clear: “The most important thing in an ecosystem is the purity of its lifeblood, the water” [19]. In their terms, the landscape is not just a resource to be protected, but a living organism to be cared for and preserved.

Winter at Eagle Rock, Sacred Ojibwe Site. (Photo by Save the Wild U.P.)

“Landscape as Public Resource”

The actor that actually owns both the surface and mineral rights on the lands leased for the Eagle Mine is the Michigan Department of Natural Resources (DNR). Its stated goals are the “conservation, protection, management, use and enjoyment of the state’s natural and cultural resources for current and future generations” [20]. Their role in the Eagle Mine case suggests that ‘conservation,’ ‘protection’ and ‘enjoyment’ may not so easily align with ‘management’ and ‘use’ in cases where different stakeholders claim different rights to the same piece of land.

The DNR owns 6 million acres of mineral rights, 4.5 million acres of public hunting land, and 2.2 million acres of (leased) farmland [21]. As owners, they walk a difficult line between extracting profit from the land for the benefit of the state, and preserving land for “future generations.” The value of the leased resources themselves can also be called into question relative the value of uncommodified natural landscapes, as a letter to DNR advocating against expansion of Eagle Mine argues:

“this public land is more valuable because its minerals have not been leased, because natural resources on the surface are not undermined or threatened by mine activity. What value does the DNR assign to silence, to the tranquility of being in a wilderness area, to the experience of seeing wild animals and sleeping to the sound of wolves howling at night?…Clearly, Eagle Mine has removed value from public land” [22].

For many opponents of the Eagle Mine, the DNR’s approval of the Kennecott Mineral Lease makes them implicit in crimes against the Upper Michigan landscape. However, their role in the management of natural resources, both above ground (flora, fauna, recreation space, timber, waterways) and below (ore deposits, subsurface water, soils) puts them in a unique position of negotiating between opposing valuations of landscape. The DNR must mediate between the contradictory values of the Upper Peninsula landscape as a tradable resource commodity, as a functioning ecosystem, and as a public natural trust.

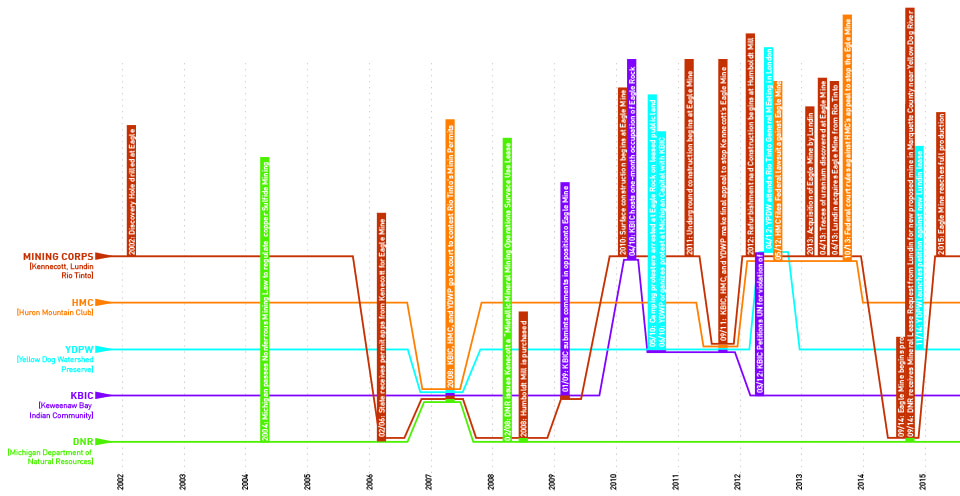

Timelines 2000-2015: The first half of the Eagle Mine saga moved relatively slowly following the discovery of the Eagle Mine lode. However, action and counter-action exploded when the DNR approved the Mineral Lease for the mine.

Verticalizing Territory

Nearly all of these groups make claims to landscape as not only horizontal, but also vertical territory — be it mineral mining/mineral operations, groundwater/surface water, or mineral rights/surface rights. At Eagle Mine, in order to access the economic value of their subterranean commodity, Kennecott first needed to secure the surface via terrestrial claims. In 2008, the Michigan DNR issued a lease for “Mining Operations Surface Use” alongside one for “Metallic Mineral Mining” for the site, thus releasing control of both surface facilities and subsurface materials to the mining interests. Surface control enabled the company to put up fencing around leased public land and to build access roads, as well as to excavate the mine itself and renovate the nearby Humboldt Mill processing facility. And as suggested by environmental groups’ concerns about groundwater uranium and acid leaching, and even atmospheric contamination as mine air is released from below-ground, [23] the impacts of mining operations are not limited to only the surface.

As suggested by the geographer Bruce Braun in his discussion of geologic exploration of Canada, [24] territory becomes verticalized when we begin to value not only the ownership of the surface, but the capital potential of the geological strata which lie beneath it. When this geological strata harbors rich deposits with potential capital gains, as in the case of the Eagle Mine, there is an impetus for verticalizing territory. The above/below-ground dichotomy is especially interesting in relation to the DNR’s surface/mineral ownership split. How can one own what’s below without owning what’s above, or vice versa? Furthermore, what does ownership of specific boundaries mean when fluid systems pass through and beyond them without limitation? The DNR is in a unique position to mediate between competing landscape claims, and perhaps define new metrics of ownership or use within the context of the diverse landscape values discussed here.

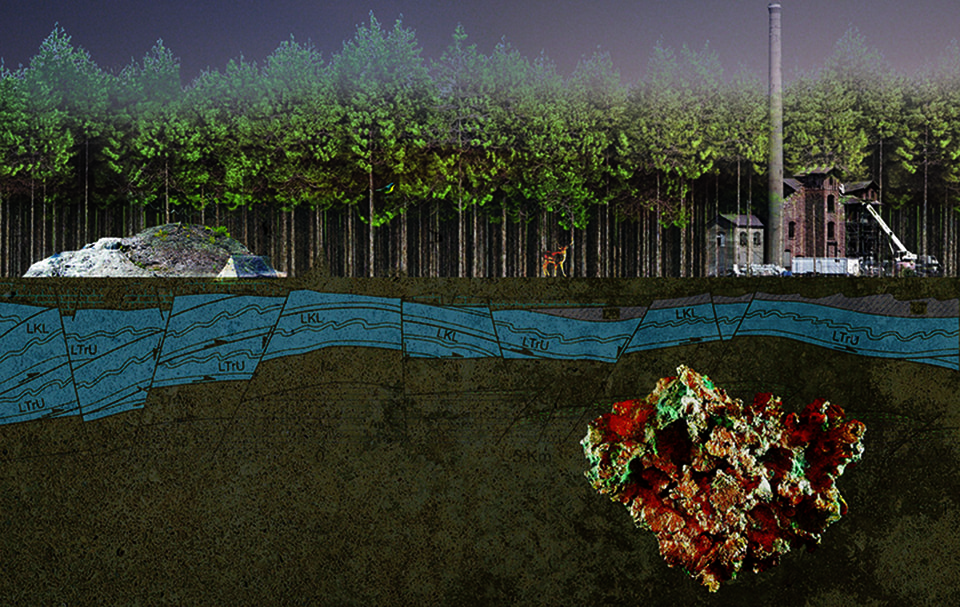

Vertical Territory: Collage showing some of the key objects of value in the sectional landscape: groundwater, wildlife, copper lodes, forest, sacred sites, and recreation spaces.

Conclusion: Re-territorializing landscape

The contested claims to the landscape surrounding Eagle Mine will continue to be tested if the prediction of a second Copper Boom in the Upper Peninsula is correct. The conflict at Eagle Mine shows how value structures lie at the heart of conflicts over landscape and resource use.

As James Proctor discusses in his case study of the dispute over ancient forests, logging rights and spotted owl habitat in the Pacific Northwest, the two (or more) sides of a natural resource conflict often correspond to different ethics of right and wrong [25]. He argues that environmentalists need to recognize the inherent value judgements in their claims for preservation as an inherent good, as opposed to the instrumental productivity of capital-producing activity (such as logging or mining). While compromise between these interests seems unlikely, introducing values into the conversation on environmental issues enables us to recognize the implicit ethics of different stances. These conversations ought to also be tied to discussions of power dynamics and spheres of influence, be they local or transnational. While all of these groups struggle for claims to the same landscape, the leverage behind them is very different.

Scales of Influence: While the landscapes of Marquette county these groups make claims to is the same, the scales of power behind them is far from equal. These visualizations of monetary control and spatial breadth — while not the only metrics for power — demonstrate some of the potential leverage behind the groups studied. Lundin Mining operates on a separate order of magnitude of money and space altogether, relative to local and regional organizations.

By acknowledging the ethics by which they operate, the different groups in the Eagle Mine case can align their scientific claims (water quality, emissions rates, resource quantities) with their political actions (anti-mining advocacy, air quality regulations, mining operations). As Latour suggests in Politics of Nature, [26] letting go of “nature” as a fetishized construct allows us to view objects (in horizontal and vertical territories) and their connection to values and politics as part of a more complex collective. Thus, what each of these groups view as “nature” or “natural resources” become part of a larger conversation about values and priorities through the lens of interconnected systems.

This essay posits that an examination of landscape claims and values should become part of the way that landscape conflict is negotiated. State agencies such as the DNR, which hold the power to grant or deny permits for extraction operations, need to recognize the competing ethics embedded in expressions of value, and to mediate between them in an open and unbiased way. New models of regulation and ownership should aim to move contested landscapes away from binary methods of ownership and use, to systems of use where the production of capital doesn’t preclude ecosystem health, cultural practice, or recreational value.

Elizabeth (Lizzie) Yarina is a joint Masters student in the Department of Architecture and the Department of City Planning at MIT, currently completing her Masters Thesis entitled “POST-ISLAND FUTURES: Design as Agency for Tuvalu’s Sinking Atolls.” Her research explores the role of design thinking in political and territorial issues, with a particular focus on climate change and natural resources. Prior to attending MIT, she worked in the field of Architectural Design at William Rawn Architects in Boston and PLY Architecture in Ann Arbor. She received her Bachelors of Science in Architecture from the University of Michigan in 2010. Lizzie grew up on a sheep farm in Tapiola, Michigan, a 60 mile drive from Eagle Mine along Keweenaw Bay and through Michigamme forest.

Elizabeth (Lizzie) Yarina is a joint Masters student in the Department of Architecture and the Department of City Planning at MIT, currently completing her Masters Thesis entitled “POST-ISLAND FUTURES: Design as Agency for Tuvalu’s Sinking Atolls.” Her research explores the role of design thinking in political and territorial issues, with a particular focus on climate change and natural resources. Prior to attending MIT, she worked in the field of Architectural Design at William Rawn Architects in Boston and PLY Architecture in Ann Arbor. She received her Bachelors of Science in Architecture from the University of Michigan in 2010. Lizzie grew up on a sheep farm in Tapiola, Michigan, a 60 mile drive from Eagle Mine along Keweenaw Bay and through Michigamme forest.