“Resource-making activities are fundamentally matters of territorialization – the expression of social power in a geographical form.” [1]

– Gavin Bridge

In the concluding section for his 1864 book, Man and Nature; or, Physical Geography as Modified by Human Action, American diplomat, philologist and conservationist George Perkins Marsh wrote: “it is a legal maxim that ‘the law…[does not concern] itself with trifles,’ de minimus non curat lex; but in the vocabulary of nature, little and great are terms of comparison only; she knows no trifles, and her laws are as inflexible in dealing with an atom as with a continent or a planet… [E]very new fact, illustrative of the action and reaction between humanity and the material world around it, is another step toward the determination of the great question, whether man is of nature or above her.”[2] In parallel, in his seminal 1967 study on the history of geographical ideas, geographer Clarence Glacken wrote that there have been three main geographic ideas since the Ancient Greece: the idea of a designed earth, the idea of environmental influence, and the idea of humans as geographic agents.[3] More recently, humans’ relationship to the earth is provided with an alternative narrative by debates on climate change as well as the idea of the Anthropocene, in which humans are now discussed as not only geographic but also as atmospheric and geological agents.

Correspondingly, in architecture and related design fields, contemporary conceptualizations for the idea of environment is presented either through the positivist overtones of management, efficiency and performance or through apocalyptic narratives of catastrophe and conservation. At this juncture, rather than seeing environment as something merely systemic, and therefore needing to be managed and maintained, or as purely natural, needing to be preserved and protected, can we instead talk about an alternative kind of geographic imagination in architecture that projects environment as aesthetic and monumental, and thus offer a renewed and a more nuanced dialogue between the representational and the material?[4] According to this formulation, geographic imagination would be a project about of a new kind of materialism that juxtaposes resource and matter with their seemingly opposing counterparts such as representation, monumentality and composition.

Museum of Lost Volumes project takes on this theoretical prompt as a starting point. As a geo-architectural fiction and a satire commentary on resource extraction, it provides an alternative focus on the mining of Rare Earth minerals. As a museum built after the depletion of Rare Earth minerals in the world after their abundant use with “green technologies,” it speculates on the preservation of geographic ruins that once belonged to the resource extraction of Rare Earth minerals mining. Since Rare Earth minerals are the backbone substance that is used in clean-energy technologies such as wind-turbines, electric batteries and solar panels, the project questions the idea of resource scarcity in the abundance of green technologies. It imagines a museum of ancient resource extraction ruins for a time when mining is an obsolete practice and treated similarly to an ancient monument or an extinct species to be housed in a museum. While rendering the geographic scale as a tangible entity, it aims to construct and alternative relationship between legibility and abstraction through the limits and potentials of design thinking. The project is comprised of five drawings, which all depict specific aspects of this imaginary museum.

While projecting on an unknown future era, Museum of Lost Volumes is slightly unfamiliar. In an attempt to expand the limits of our disciplinary imaginary, it employs familiar architectural strategies on what is considered to be unfamiliar within a disciplinary setting—in this case mining—and brings it into architectural consciousness. Perhaps in the same manner that Karl Friedrich Schinkel found beauty in the English factories, Walter Gropius in the American grain silos, and Le Corbusier in the ocean liner, it points to the ruthless territorial geometries of mining through architectural imagination. Rather than promoting a project of new realism—neither super realism (righteous scenario planning or environmental engineering of data) nor extreme surrealism (architectural sci-fi)—it aims to unravel the potentials of the unfamiliar precisely at the opposite end of the spectrum through abstraction. While speculating on humans’ relationship to the earth, it situates the idea of the slightly unfamiliar as an alternative positioning between the geographic and the aesthetic, while being strategically situated between legibility and abstraction.

1.

UNITED COUNCIL OF RARE EARTHS

Once upon time in the Zero-carbon Hedonistic Era, the entire world was finally sustainable. Clean-energy technologies were abundant and ubiquitous. Large quantity of energy-efficient light bulbs, wind turbines, electric car batteries and solar panels would come with a price, however. Since all of these clean-energy technologies relied on Rare Earths—a group of seventeen chemical elements and their abundant extraction from the earth’s surface—significant worldwide increase in their demand led to the scarcity of these minerals. Nearly all of the Rare Earths were discovered in the 19th century but their use mostly proliferated in the Zero-carbon Hedonistic Era because of their association with green technologies. A report by the US Department of Energy, prepared back in 2011, had warned the world about this critical issue yet the danger was quickly forgotten soon after.[5] Not alarmed by the possible tragic outcomes of the further mining of these minerals, the world celebrated their delirious consumption with even more wind farms, car batteries and solar panels until very little of these minerals were available. Soon after the depletion of these precious resources were officially announced, in an attempt to prevent major geopolitical conflicts, United Council of Rare Earths was established to promote international co-operation regarding this matter.

In its inaugural meeting, the Council members drafted the text of the Declaration by the United Council of Rare Earths, which was signed by all countries. After a long meeting, the unanimous vote was held to ban further Rare Earth mining and to build a museum that would house and preserve remaining Rare Earth mines of the world, and would carry their legacy to future generations. The museum was named as the Museum of Lost Volumes.

2.

THE ROOM OF FLOATING VOLUMES

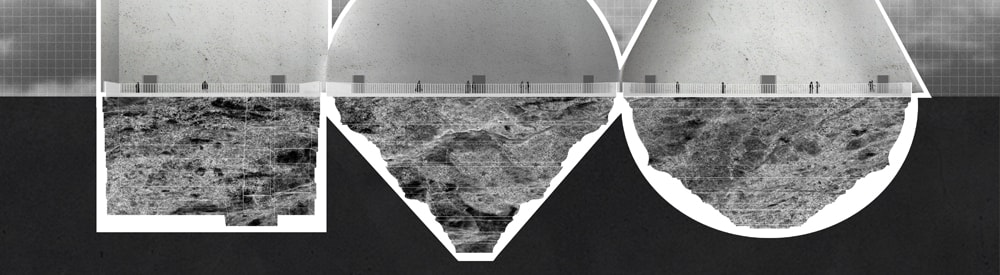

The Museum of Lost Volumes was composed of many rooms. Each room was dedicated to different minerals while exhibiting a particular volumetric quality regarding these mines. The first room was divided into three parts and was connected with a single bridge that looked over the three different minerals. The bridge felt so small in this large space, and so did the visitors. While the mines were placed into the underground exhibiting the extraction processes of how they are removed from the earth, the visitors walked through the bridge observing them. The section profile of these colossal rooms was a monument to the mines as well, as they resembled the profile of a particular resource extraction. While walking along the bridge, the visitors felt as if they were floating in between the gigantic hollowness of the volume underneath and the massive spatiality of the ceiling above. Admiring the commemoration of these mines as volumes, visitors left the room completely mesmerized.

3.

THE ROOM OF SPECIES

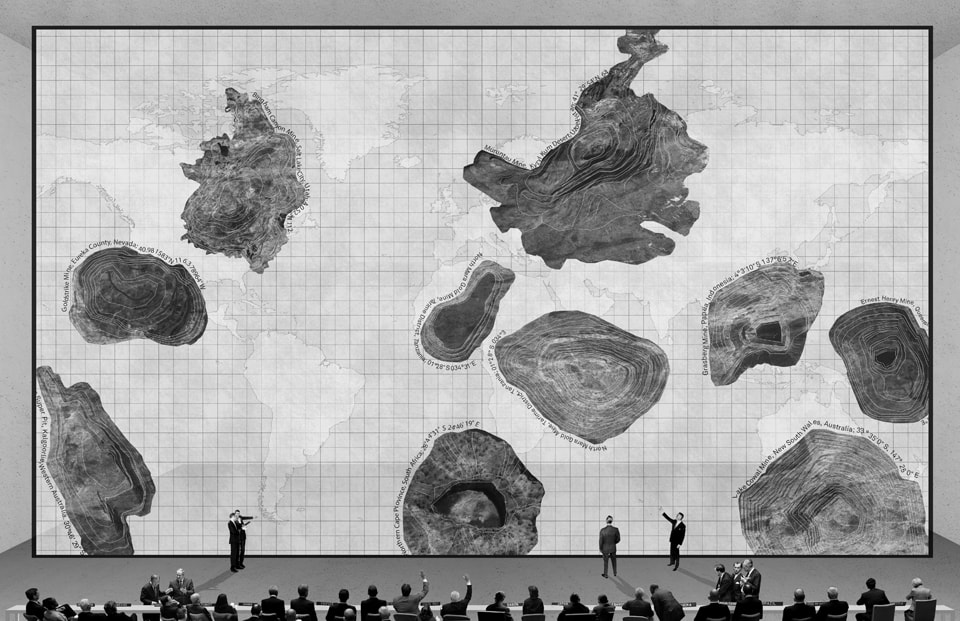

The next room of the museum showcased inverted pieces of Rare Earth mines from each of the seventeen mineral types that were placed carefully in preserved glass boxes. Varying in size, shape, and texture, each mine piece was filled with different stories and different lives. Visitors walked from one box to another, analyzing these glowing mountains so up close. One child put his nose up to the glass box, trying to get a much closer view to one of the minerals. “Why are these monuments trapped?” he asked to his mother. The mother looked thoughtfully. “If you are preserved and showcased, that means you are rare and very precious,” she said. “These monuments are actually at peace.”

4.

THE ROOM OF PLATONIC VOLUMES

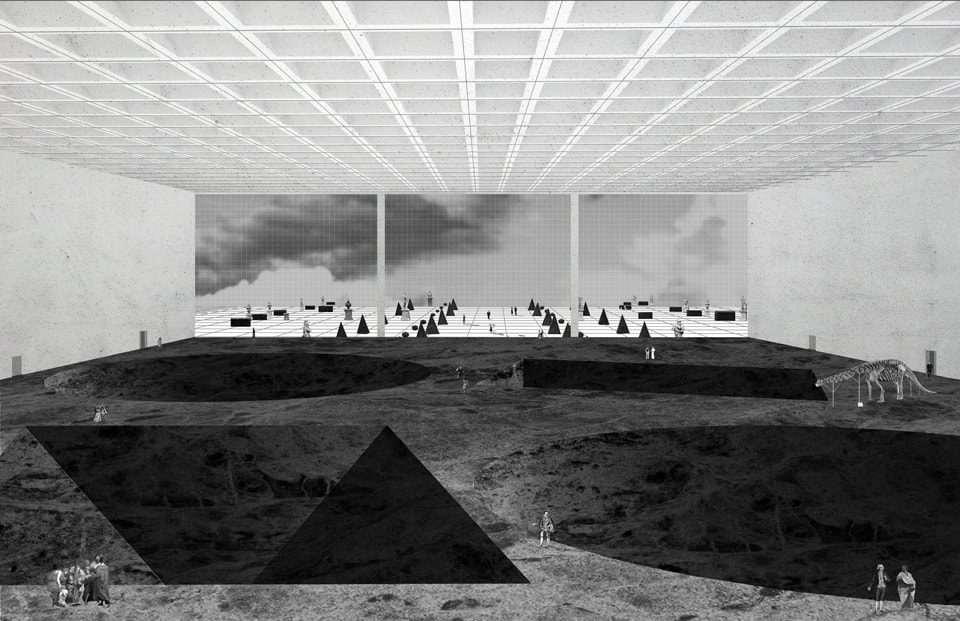

The next room was a large continuous surface from which large platonic volumes were carved out. While each volume represented a particular Rare Earth mine in the world, the mine sizes were compared to one another in scale within the space of the room. Walking along the edges of these volumes, one visitor thought about the amount of neodymium extracted from one particular mine because of the sheer mass of the volume represented. “How many wind turbines would this make?” he said to himself. In this room, the represented lost volume was not bounded by a box or was to be viewed from a bridge like it was in the other rooms of the museum. Having the chance to walk on the actual matter and to be able to touch it was in itself a sublime feeling. The surface of the mineral felt smooth, but looked textured. The visitors were both astounded and heartbroken that these volumes were all lost from the earth’s surface.

5.

THE GRAND TOUR:

RARE EARTH REPLICAS

Last section of the museum was dedicated to the museum’s Grand Tour, an excursion of several 1:1 scale Rare Earth replicas. Since Rare Earth mines were too large to fit even in the specially constructed large rooms of the museum, these replicas had to be observed in the outdoors. Accordingly, in order for their total volume to be fully comprehended, the Rare Earth replicas needed to be seen from a far distance. Because of their colossal size, they were placed on a vast flat land. The distance of the replicas from the museum building were determined through the geographic distance to the visible horizon, approximately 2.9 miles from the entrance door of the museum for an observer standing on the ground with an average eye-level height. While all the replicas were inverted upside down reminding of the ziggurats from ancient civilizations, visitors took the Grand Tour to these geographic ruins to be terrified with their artificial magnificence. Millions of visitors would visit the museum and take the Grand Tour to these inverted monuments every year. When they went back to their homes after their visit to the Museum of Lost Volumes, they would be filled with admiration, anxiety and thankfulness for the resources of this rare thing called the earth.

Author’s note: Museum of Lost Volumes was awarded with an Honorable Mention in Blank Space Fairy Tales Space Competition in March 2015. Along with the other winners of the competition, the project has just been published in Fairy Tales: When Architecture Tells a Story Volume 2 (New York: Blank Space Publishing, 2015). The author would like to acknowledge and thank Anastasia Yee and Melis Ugurlu for all their help with the project.

Neyran Turan is an assistant professor at Rice University School of Architecture, a co-founder of NEMESTUDIO, design collaborative based in Houston. She received her doctoral degree from Harvard University Graduate School of Design (GSD) and holds a masters degree from Yale University School of Architecture. Turan’s work draws on the relationship between geography and design to highlight their interaction for new aesthetic and political trajectories within architecture and urbanism. She is founding chief-editor of the Harvard GSD journal New Geographies, and is the editor-in-chief of the first two volumes of the journal: New Geographies 0 (2008), New Geographies: After Zero (2009). Some of her recent writings have been published in Thresholds, SAN ROCCO, Conditions, MASCONTEXT, Bidoun, MONU, and ARPA Journal.

Neyran Turan is an assistant professor at Rice University School of Architecture, a co-founder of NEMESTUDIO, design collaborative based in Houston. She received her doctoral degree from Harvard University Graduate School of Design (GSD) and holds a masters degree from Yale University School of Architecture. Turan’s work draws on the relationship between geography and design to highlight their interaction for new aesthetic and political trajectories within architecture and urbanism. She is founding chief-editor of the Harvard GSD journal New Geographies, and is the editor-in-chief of the first two volumes of the journal: New Geographies 0 (2008), New Geographies: After Zero (2009). Some of her recent writings have been published in Thresholds, SAN ROCCO, Conditions, MASCONTEXT, Bidoun, MONU, and ARPA Journal.

Notes:

[1] Gavin Bridge, “Resource geographies I: Making Carbon Economies, Old and New,” Progress in Human Geography 35:6 (2010): 825.

[2] George P. Marsh, Man and Nature; or, Physical Geography as Modified by Human Action (New York: Charles Scribner, 1864), 548-549.

[3] Clarence Glacken, Traces on the Rhodian Shore: Nature and Culture in Western Thought from Ancient Times to the End of the Eighteenth Century (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967), vii.

[4] For a more extensive discussion on this question, see: Neyran Turan, “How Do Geographic Objects Perform?” ARPA Journal 03 (July 2015). Full article is available to view online at: http://www.arpajournal.net/how-do-geographic-objects-perform/

[5] US Department of Energy, “Critical Materials Strategy,” December 2011, http://energy.gov/sites/prod/files/DOE_CMS2011_FINAL_Full.pdf. Also see, Nicole Jones, “A Scarcity of Rare Metals Is Hindering Green Technologies” Yale Environment 360 (18 November 2013), accessed January 23, 2015.