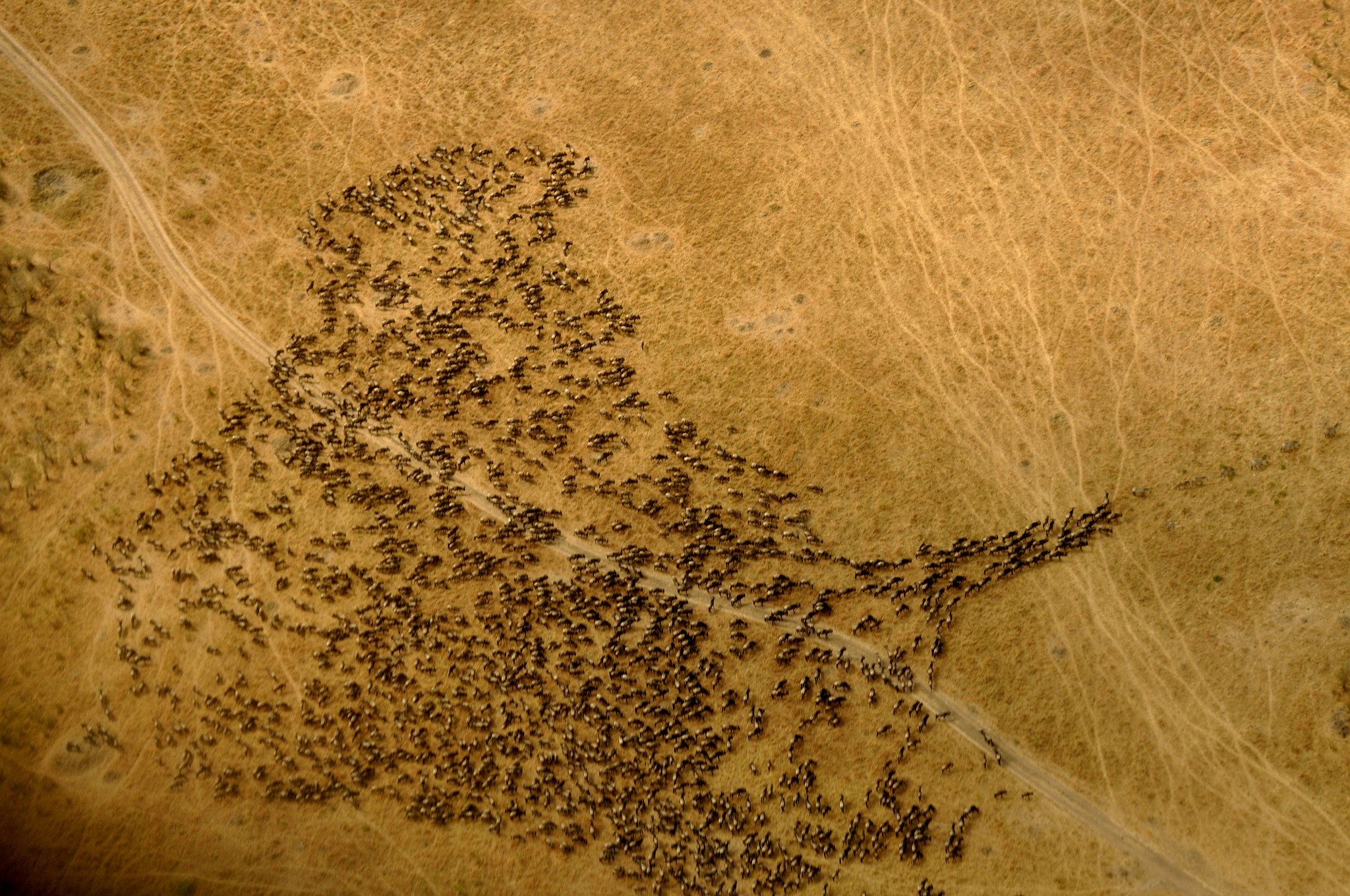

Populations move. Plants disperse genes by way of seeds and pollen; wetlands accrete and erode; animals forage, mate, roam. Humans leave their homes in search of work, land, education, safety, and opportunity. Migration is a process by which organisms track resources, discover, and escape. The patterns of migration reflect spatial and temporal changes in the landscape. Migration is a cipher and a signifier — it helps us unravel the invisible threads that hold together an ecosystem.

Broadly speaking, migration can be defined as “the mass directional movements of large numbers of a species from one location to another” [1]. The term is used to describe a diverse array of patterns, from the intercontinental movements of Arctic terns and humpback whales to the micro-movements of tiny shore animals following the tidal cycle. Migration plays out over time, across scales, and in specific geographies.

Photo by T. R. Shankar Ramanhandel

Biologists and population ecologists often focus on seasonal, round-trip movements between discrete locations. Such seasonal migrations are essential to the survival and resilience of many populations, as communities respond to changes in resource availability or habitat quality over the course of the year. For some long-lived species, individuals make the journey between winter and summer ranges year after year. For others species, such as the painted lady (Vanessa cardui) or monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus), migrations can occur over multiple generations, with one individual incrementally following the shifting season and accompanying resources northward or southward, then passing the baton to its offspring to continue the journey.

For humans too, migration is a basic survival strategy. Humans have always moved, and often over very long distances [2]. The large-scale movement of people goes back more than a hundred thousand years when early homo sapiens began migrating out from the African continent. Just as other species migrate in reaction to resource availability, habitat quality, and stress or disturbance — human populations move (voluntarily or involuntarily) for a wide range of motivations.

Migration, therefore is a broad construct that can describe flows of populations as diverse as the seasonal patterns of migrant laborers and nomadic herders, the relocation of populations in response to earthquakes or civil wars, the zealous journeys of missionaries or explorers, the voluntary seasonal travel of retirees, or the involuntary removal of populations ensnared by mass incarceration. The framework of migration studies has also been used to study complex and traumatic histories such as the forced migration resultant of ethnic cleansing or the transatlantic slave trade. These large-scale movements of individuals and communities from one location to another, or one way of life to another, is now recognized as having far-reaching effects on culture, language, genetics, law, economics and the environment.

Nomadic ger disassembled and loaded in just a few hours in the countryside outside Ulaanhus Soum, Bayan Olgii, Mongolia. A single truck was sufficient to carry two families’ belongings including two gers, furniture and stoves. Photograph by Stephanie Carlisle

International Migration

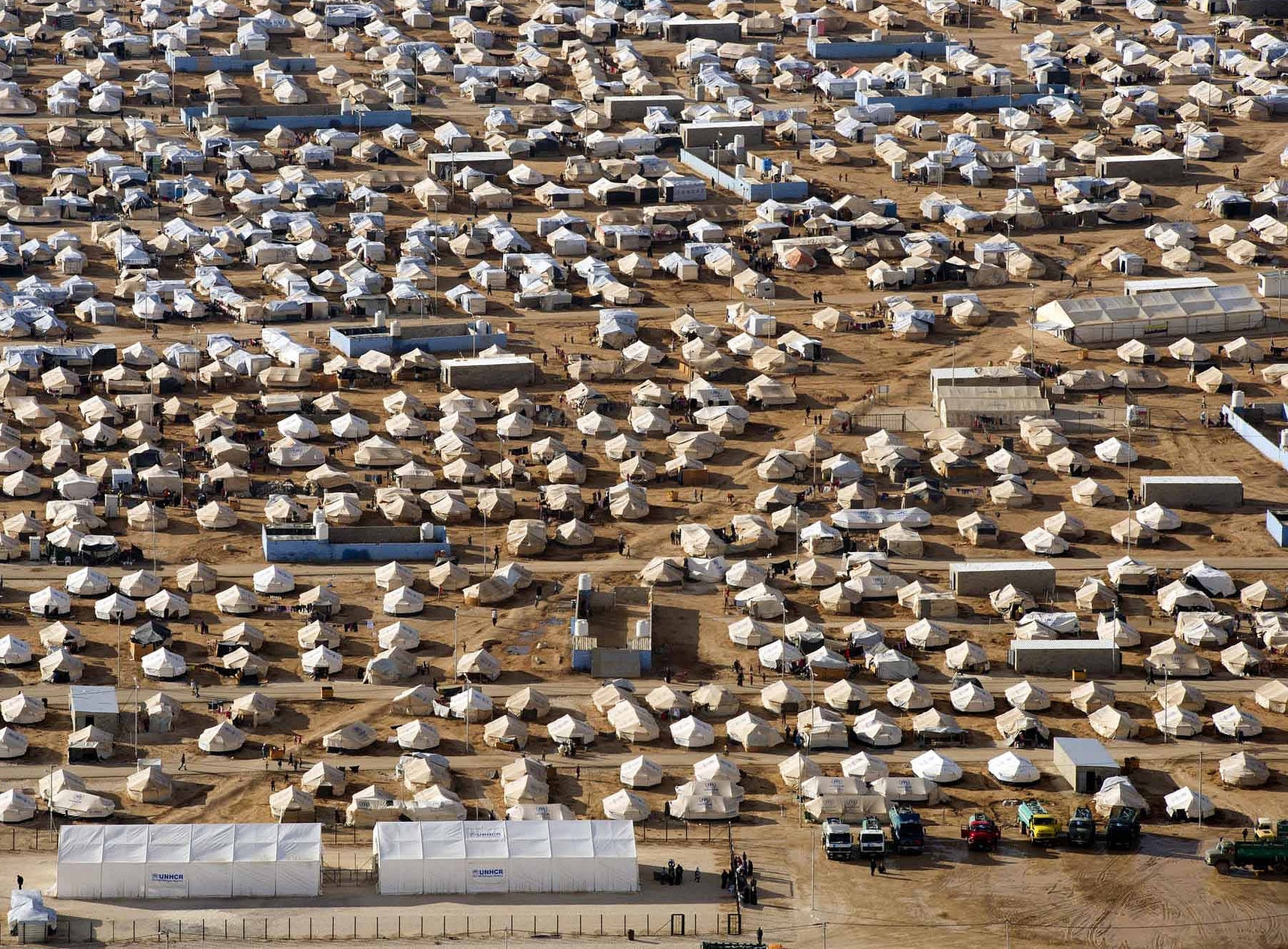

The total number of international migrants today is estimated by both the United Nations 2015 Migration Report and the Pew Research Center at 244 million, or roughly three percent of global population — the highest number of people on the move ever recorded, and a 41% increase compared to the year 2000 [3]. Over 65 million people are forcibly displaced from their homeland, and nearly 20 million of those individuals are refugees [4]. Conflict, injustice and systemic violence are not new to history, but today’s ongoing crises and inequalities occur amidst a context of increased human mobility, globalization and interconnectedness.

Nations hosting large refugee populations bear a disproportionate burden as long-term responses to crises around the world remain “ad-hoc, incomplete and uncoordinated,” according to the United Nations Summit for Refugees [5]. Furthermore, the impacts of large-scale movement of refugees and migrants, are felt at every point across the diverse landscapes that serve as places of origin, transit, or destination. In pursuing a better life, migrants take incredible risks and travel at great expense. In their countries of destination, the arrival of foreigners in large numbers have been met with the full spectrum of human emotions and actions — from deep solidarity and charity to racist protest and a sharp uptick in hate crimes and discrimination.

An aerial view of Za’atri refugee camp near Mafraq, Jordan. Photo by United Nations Photo

Rural to Urban Migration

China, meanwhile, is hosting what may be the largest internal mass migration in history. According to Kam Wing Chan, professor of geography at the University of Washington, over the last three decades, over 200 million rural Chinese have moved from the countryside throughout inland China to the rapidly growing industrial and financial urban centers on the coast, such as Guangzhou, Beijing, and Shanghai [6]. These migrants are not foreigners in their new homes and don’t often evoke the same narrative of diluting national identity, but they have brought with them new challenges of social transformation, and have fueled demand for a massive expansion in infrastructure, in housing, and in other government services. Rapid urbanization in China, fueled by rural migrant labor, compulsory resettlement programs, and the arrival of manufacturing from around the world, has created its own suite of social and ecological challenges.

New urban development in Chongqing, China. Photo by Thomas Bächinger

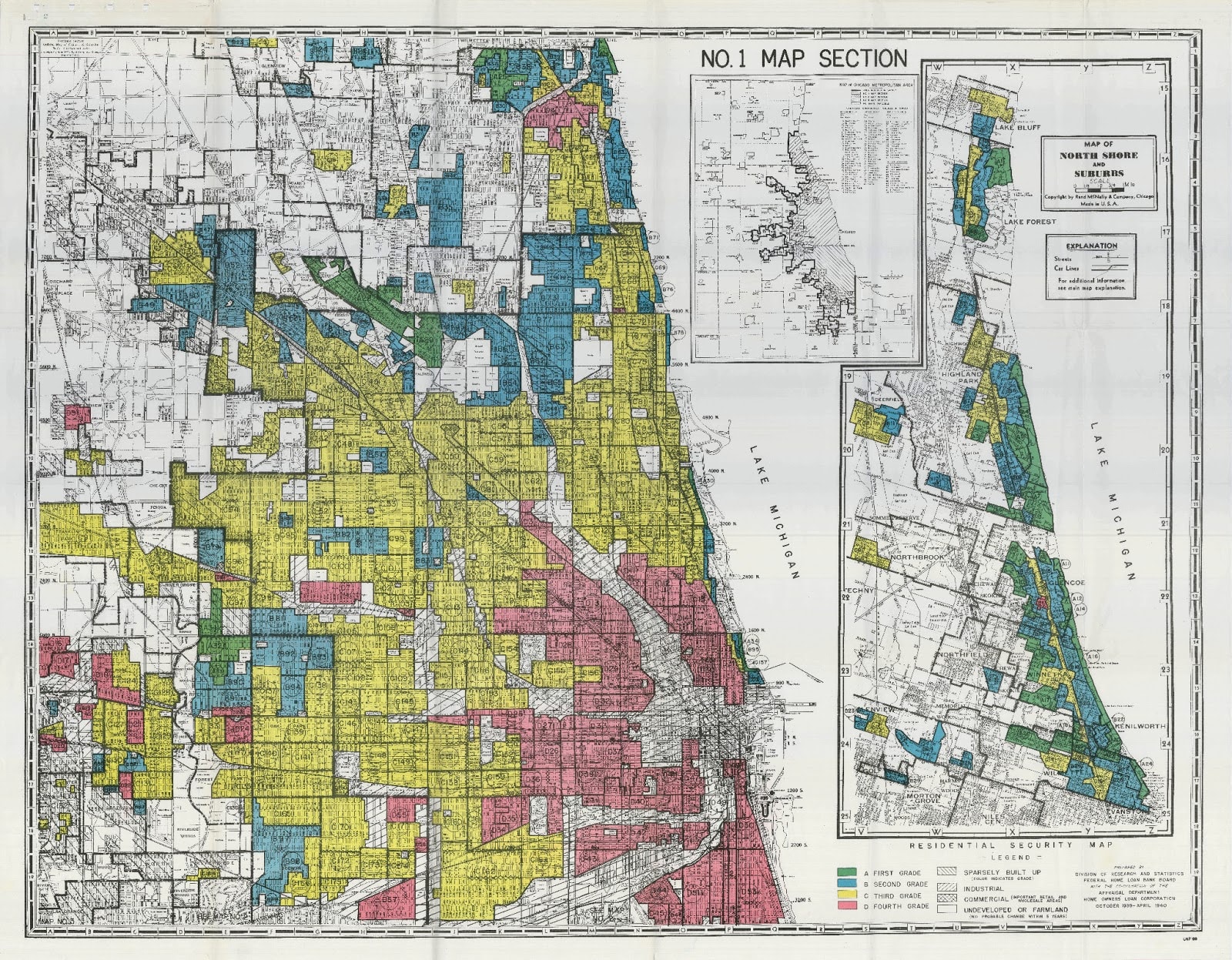

In retrospect, such migration events often have the effect of injecting cultures with diverse and hybrid elements, forging new ideas and cultural innovations in the places they settle. America’s Great Migration is one such example, in which close to 6 million African Americans moved from the predominantly rural South between Reconstruction and the 1970’s to the growing northern and western cities of New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, Los Angeles and Detroit, to name a few [7]. Isabel Wilkerson, the author of The Warmth of Other Suns, describes the first steps of the Great Migration as the accumulation of millions of individual decisions, which nonetheless set into motion a profound reshaping of American life and culture, ultimately transforming the character of cities, music, art, politics, and community dynamics [8]. At the same time, the movement of black and brown people into largely white cities created new tensions and conflict, giving rise to the creation of urban ghettos, exclusionary zoning, institutionalized discrimination and white flight to suburbs — urban dynamics whose legacies are still with us today [9].

Home Owner’s Loan Corporation Redlining Maps of Chicago, 1939. Green = “Best”; Blue = “Still Desirable” ; Yellow = “Definitely Declining” ; Red = “Hazardous”

Language and Anxiety: how we talk about migration

Migration is a fundamental process that sustains communities, but it also represents our greatest social anxieties. As such, it has become difficult to speak of migration of any sort without entering a semantic minefield. Today, the language of migration is political; perhaps this has always been the case. The words that we use to talk about migration matter and the language of migration is constantly shifting [10].

Migrant, emigrant, immigrant, asylum seeker, refugee, alien: these are all official categories [11]. Recently, the perceptions of these words in politics and popular media have become more negative. According to Dr. Emma Bryant, a researcher who specializes in propaganda, migration, and media studies at the University of Sheffield, “negative associations with these categories really do cloud how we analyze the facts. The important takeaway is that including context about why people are traveling and trying to see them as human beings that are affected by social and economic pressures and political transitions that are taking place around the world is the key issue” [12].

The words we choose matter. Bryant also points to linguistic trends commonly used to disparage or marginalize people, such as the tendency to borrow the language of natural disasters or the apocalypse — deluge, flood, swarm, waves, parasites — which has the double effect of amplifying fear while also dehumanizing people. Additionally, the lens of race and class also affects the words we use in conversations about migration. Brits that retire to Spain or go to Saudi Arabia to work for the oil industry tend to refer to themselves as “expats,” not migrants. In popular media, “migrant” is primarily applied to outsiders, to people with a different skin color, religion or socio-economic status than the majority group. For further emotional effect, the word “illegal” is often added as a modifier of someone’s status when nothing illegal at all has happened [13].

Clockwise from top left: U.S., 2016; Berlin, 2016; Hamburg, 2016; Lausanne, 2015. Photos by Lorie Shaull; Majka Czapski; Rasande Tyskar; Gustave Deghilage

Curiously, the language of migration and social anxiety has even seeped into the natural sciences, igniting fierce debate. In June 2011, a group of ecologists published a short paper in the journal Nature, titled “Don’t judge species on their origins,” in which they argued that the threat posed by alien or exotic species have been overstated and that the field of invasion biology draws from the flawed and problematic notion that a “native” condition can and should be restored [14]. The article drew from ecologist Mark Davis’ ongoing critique that the words that ecologists and conservationists had adopted, to much effect, had become counterproductive, going as far as to argue that “classifying biota according to cultural standards of belonging, citizenship, fair play, and morality does not advance our understanding of ecology” [15].

By July 2011, several fiercely written commentaries and op-eds were published in the journals Science and Nature, on behalf of hundreds of biologists, conservationists and environmental managers, fiercely disagreeing with the premise of Davis’ piece, offering well-reasoned perspectives and insight into conservation practice, defending their field of study, but also continuing to use terms that explicitly reference the language of nativism, policing, surveillance, and crisis [16].

It’s not that scientists just disagreed about the careful introduction of species and the creation of novel assemblages — it was in large part the explicit reckoning with language that was so contentious [17]. The debate has led to the surreal spectacle of conference rooms filled with tenured ecologists and evolutionary biologists arguing over whether or not foundational terminology used to describe flora and fauna is xenophobic. How did we get here?

According to some researchers, what may connect these fierce debates over the language of migration, be it human or non-human, are pervasive societal feelings of a loss of control, a lack of certainty about the future, a sense that the world is changing far too quickly, that old modes of making sense of our environment might no longer be valid. Scientists Paul Robbins and Sarah Moore from the University of Wisconsin-Madison pointed to the debate over Invasion Biology in 2011 as emblematic of “Ecological anxiety disorder,” which they believe is fundamentally a response to rapid environmental change and the rise of novel and unprecedented ecosystems that “challenge the scientific, as well as cultural core of many disciplines” [18]. Perhaps the clearest trigger of this anxiety is the concept of the Anthropocene.

Similar emotions can be found lurking beneath other theories that have more recently made their way into popular science, such as the Great Acceleration, the Sixth Extinction, novel ecosystems, extinction debt, and the specter of irreversible climate change connecting them all. The underlying notion is that the relationship between man and nature has fundamentally changed and that despite our species’ newly recognized power, we don’t seem particularly in control.

Despite the care we may exercise with our words, our landscape management practices, our immigration policies, or our urban infrastructure, ever more migration can be anticipated — of species, of habitats, and of human populations. The questions for society are open-ended and challenging.

What will be the appropriate level of intervention?

Which communities are “worth saving”?

What exactly is the value of “native” species or a “natural” state?

Are we trying to Make Nature Great Again?

Mountain goats in Glacier National Park. Photo by Tom Driggers

Connectivity, Visibility, and Barriers

Migration relies on complex networks of relationships that can easily be damaged or disturbed. Over time, well-established movement corridors become blocked. Barriers can take on a range of forms, often innocuous in their own right but potentially devastating to a population’s ability to migrate: roads and fences severing seasonal migration routes that animals have relied on for hundreds or thousands of years; dams blocking fish from returning to their spawning grounds [19]. The disappearance of coastal wetlands due to urban development and sea level rise disturbing the tenuous network of stopover grounds that long-distance migratory birds depend on to feed and refuel on their way south or north. Beachfront development restricting the natural migration of sand dunes and wetlands, a phenomenon memorably known as “coastal squeeze.”

Other times, barriers are intentionally erected. In response to the social anxieties sparked by large-scale immigration, some countries are putting up new border walls and fences, a physical manifestation of the unwelcome borne towards migrants.

These barriers are explicit agents of violence. Still, migrants seek out paths of opportunity and least resistance. Thus, as land routes from the Middle East and Africa to Europe were systematically closed off in Greece, Bulgaria, Hungary, Slovenia between 2012 and 2015, many more migrants took to the sea, knowing the risk but choosing to continue moving [20]. At the U.S.-Mexico border, the consolidated flow of migrants formerly concentrated at border towns like Nogales and El Paso has been impeded since 1994 by steel walls and increased enforcement [21]. As a result, migrants and refugees have been pushed further out into the harsh landscape of the Sonoran desert.

In The Land of Open Graves: Living and Dying on the Migrant Trail, anthropologist Jason De León argues that “migrants have been purposefully funneled into the desert through various enforcement practices, a tactic that has enabled Border Patrol to outsource the work of punishment to actants such as mountains and extreme temperatures” [22]. The resultant death toll has been severe. By conscripting landscape to be the enforcer and agent of violence, governments can claim plausible deniability, avoiding the moral outrage and bad optics of personally killing thousands of people upon their country’s doorstep.

Installation of hundreds of backpacks abandoned by migrants crossing the Sonoran desert, part of the exhibition State of Exception/Estado de Excepción created by artist/photographer Richard Barnes and artist/curator Amanda Krugliak in collaboration with anthropologist Jason De León. Photo by Nicholas Pevzner

Is promoting connectivity always the answer? In some places, the newfound connectivity of international shipping and air travel has enabled invasive plants and animals to spread, making native populations more vulnerable to invasion. On formerly remote islands, waves of non-native plants and animals have caused local extinctions. Infections spread much more extensively and quickly in our connected world. The design of our cities and landscapes can either facilitate or inhibit migration. Which flows do we want to encourage, and which to block?

As habitats shift in response to global climatic changes, and development patterns push up against long-established migration patterns, some of which are coming into focus for the first time, how can cities and infrastructure be designed to be more mindful of these flows? How can populations on the move keep up, and what kind of assistance can designers, planners, land managers, and restoration ecologists offer?

Syrian and Iraqi migrants arriving in Greece. Photo by Ggia

The Essays

This past year, hardly a week has gone by in which the topic of migration has not been in the news, or in which a new study on the effects of migration has not been published. This year, both Science and Nature ran special issues on Human Migration. The Economist included a special report on the topic, numerous academic journal devoted thousands of pages for specialized and focused perspectives on migration [23]. Last year, the United Nations General Assembly hosted its first high-level summit to discuss large movements of refugees and migrants and plan a coordinated global response [24]. The World Economic Forum’s Global Risk Report mentioned the global migrant crisis as one of the top five drivers of risk and uncertainty in the world for three years in a row [25].

It has made the curation and editing of this issue fraught, albeit timely, as month after month, another national election, “natural” disaster, or geopolitical event has thrown the topic back into the spotlight. It is simply not possible to fully explore the richness and intricacies of this topic in fourteen pieces. Instead, in this issue of Scenario Journal, we have brought together a few stories that explore select facets of the complex story of migration, told from a range of disciplinary perspectives.

Grounding the discussion in the natural sciences, we have an overview of migration processes by restoration ecologist Steven N. Handel, spanning the widest range of scales and time frames, from the march of species across continents to the micro-movements of rhizomes along the forest floor. In the face of pressure from migrating habitats, he unpacks promising and controversial ideas like “assisted migration,” while articulating the limits of this form of “extreme gardening.” Meanwhile, Roland Kays discusses the challenges of studying animal migration in the field, and the fascinating technological advances that are allowing researchers and the public to see many animal trajectories at high resolution, some for the first time.

The materials that constitute our built environment similarly move through space, and can be tracked: Mike Yengling looks at how ordinary American building materials — and even entire buildings — migrate across the US-Mexico border to become reconstituted in the urban fabric of Tijuana. Alex Klatskin zooms out to look at how materials and goods travel around the world, thanks to the innovations of containerization and the port infrastructures that support it and fast-forwards to imagine the value that these vast distribution landscapes may come to have as climate change disrupts traditional patterns of coastal development. Taking on a different coastal landscape amid the pressures being unleashed by climate change, Fadi Masoud looks at Floridian coastal development, where climate disruption is already occurring and outlines a forward-looking zoning code that is able to absorb the fast-evolving four-dimensional dynamics along the migrating coast.

Historic migration and urbanization patterns have shaped and defined specific landscapes; several pieces investigate the how territorial reorganization can realign historic migration patterns, or initiate new ones. In the vast hardscrabble territory of the Australian interior, Karl Kullmann looks at the shrinking rural towns depopulated by rural-to-urban out-migration. His piece offers design strategies to direct a process of controlled decline, alongside a process of ecological restoration. Wim Wambecq and Bruno De Meulder seek to direct the un-building of successive layers of urban infrastructure while reshaping the hydrological and forest systems in the Brussels region with targeted design interventions, so as to unblock the migratory corridor of the Southern Senne valley for plant and animal movement.

In “The Continental Compact: Eastward Migration in a (New) New World,” Ian Caine and Derek Hoeferlin offer us a manifesto for a future of increasing droughts and water scarcity. It proposes a radical realignment of urbanization and infrastructural investment under a rubric of Hydrologic Urbanism, where we stop bringing water to people and instead bring the people to the water. Extending the subversive polemical vision even further, the Belgian collective Traumnovelle offers a story of the lucky climate migrants able to relocate in high style to a vast new continent, the colonial impulse critically re-examined in light of migration’s pervasive inequalities.

The balance of pieces turn their attention to the material and political challenges and anxieties that refugees, asylum-seekers, and undocumented immigrants confront amid their daily struggles. Tami Banh and Antonia Rudnay analyze the personal journey of a single specific Syrian refugee, spatializing his experiences against the backdrop of his interactions with the abstract political landscape of Europe and its borders. Maria Gabriella Trovato visits Syrian refugees in one of the many informal tent settlements in Lebanon, and reports on how such emergency landscapes suffer from a fractured sense of belonging. Through design-build interventions, she points to several strategies for designing flexible spaces that can begin to better create community space for refugees.

In “Travel by Night,” Audrey Burns Leites follows the path of a refugee in legal limbo as he seeks to navigate the long and complex bureaucratic journey towards citizenship, unpacking the power and nuance of the physical documents that distinguish those that officially “belong” from those at the edge of society’s shadows. Finally, Eduardo Rega offers a radical vision of an urban fabric, suspended between dystopia and “real utopia,” where clever spatial tactics at the architectural scale extend the “sanctuary” of neighborhood institutions to shelter undocumented immigrants from the enforcement actions of I.C.E.

The pieces in this collection engage with the patterns of migration in an ecological, political, social, and material mode. They grapple with what it means to describe, design and represent migration and movement. This topic is evolving and will continue to unfold with ever-more interconnections, and unforeseen feedback loops as other social and biophysical systems respond to the dynamics stirred up by this era of profound planetary change. We hope that we have offered a few ways into this fraught and contentious — but fascinating — topic, and hope that you continue this conversation.

SCENARIO 6: Migration Cover Image by Rick Bohn

Table of Contents Header Image by United Nations Photo

Feature image by Don McCullough

Stephanie Carlisle is a designer and environmental researcher whose work focuses on the relationship between the built and natural environment. She works in the research group at KieranTimberlake Architects. She is a co-editor of this issue and teaches Urban Ecology in the Department of Landscape Architecture and Regional Planning at the University of Pennsylvania School of Design.

Nicholas Pevzner’s research focuses on the public and civic potential of infrastructure, and explores the role that infrastructural landscape moves can play in structuring and sustaining healthy cities. He teaches in the Department of Landscape Architecture and Regional Planning at the University of Pennsylvania School of Design. He is a co-editor of this issue.

Notes

[1] Michael Begon, Colin R. Harper Townsend, L. John, R. Townsend Colin, and L. Harper John. Ecology: from individuals to ecosystems. (New York: Wiley Press, 2006).

[2] Held, David. “Climate Change, Migration and the Cosmopolitan Dilemma.” Global Policy 7.2 (2016): 237-246.

[3] Pew Research Center, “International migration: Key findings from the U.S., Europe and the world.” December 15, 2016, http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/12/15/international-migration-key-findings-from-the-u-s-europe-and-the-world/

United Nations, “International Migration Report 2015,” (Report, United Nations, 2016) http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/publications/migrationreport/docs/MigrationReport2015.pdf

[4] UNHCR, “Global forced displacement hits record high,” June 20, 2016, http://www.unhcr.org/en-us/news/latest/2016/6/5763b65a4/global-forced-displacement-hits-record-high.html

[5] United Nations, “United Nations Summit for Refugees: Addressing large numbers of migrants,” http://refugeesmigrants.un.org/

[6] Kam W Chan, “Migration and development in China: trends, geography and current issues,” Migration and Development. Vol 1, No 2, December 2012, 187-205

[7] Jill Lepore, “The Uprooted: Chronicling the Great Migration,” The New Yorker, September 6, 2010. http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2010/09/06/the-uprooted

[8] Isabel Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration (New York: Vintage, 2011).

[9] Fresh Air, “The Great Migration: The African-American Exodus North,” Interview with Isabel Wilkerson. September 13, 2010, http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=129827444

[10] Helen Zaltzman, “Allusionist 53: The Away Team,” The Allusionist. Podcast. March 31, 2017, https://www.theallusionist.org/transcripts/migration

[11] UNHCR definition of refugee..

[12] Zaltzman,”Allusionist 53: The Away Team”

[13] Greg Philo, Emma Briant, and Pauline Donald. Bad News for Refugees. (London: Pluto Press, 2013).

[14] Davis, Mark A., Matthew K. Chew, Richard J. Hobbs, Ariel E. Lugo, John J. Ewel, Geerat J. Vermeij, James H. Brown et al. “Don’t judge species on their origins.” Nature 474, No. 7350 (2011): 153-154.

[15] Mark A. Davis, Invasion Biology. (London: Oxford University Press, 2009).

[16] Daniel Simberloff, “Non-natives: 141 scientists object.” Nature 475, No. 7354 (2011): 36-36.

The most public such rebuttal of Davis et al.’s piece was published in the very next issue of Nature in which Simberloff, speaking on behalf of 141 scientists stated that, while not all introduced species are inherently bad or harmful, a newly introduced species “should be carefully watched” and that “the public must be vigilant of introduction and continue to support the many successful management efforts.” (Simberloff, 2011). The very next op-ed in the same issue began with the simple statement “bias against non-native species is not xenophobic.” (Alyokhin, 2011).

[17] Paul Robbins and Sarah A. Moore. “Ecological anxiety disorder: diagnosing the politics of the Anthropocene.” Cultural Geographies 20, No. 1 (2013): 3-19.

[18] Robbins and Moore. “Ecological anxiety disorder: diagnosing the politics of the Anthropocene.”

[19] Daniel Glick, “End of the Road?” Smithsonian Magazine. January 2007, http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/end-of-the-road-1-142780847/

Wildlife Conservation Society. “The Path of the Pronghorn,” National Geographic, December 6, 2013, http://voices.nationalgeographic.com/2013/12/06/path-of-the-pronghorn-leading-to-new-passages-part-3/

[20] Dionne Searcey and Jaime Yaya Barry, “Why migrants keep risking all on the deadliest route,” New York Times, June 22, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/22/world/africa/migrants-mediterranean-italy-libya-deaths.html

[21] Jason De León. The Land of Open Graves: Living and dying on the migrant trail. (University of California Press, 2015).

[22] De León, 2015. 61.

[23] Elizabeth Culotta, “Human Migrations,” Science, 19 May 2017: Vol. 356, Issue 6339 http://science.sciencemag.org/content/356/6339

“Human Migration,” Nature, March 1, 2017 http://www.nature.com/news/human-migration-1.21521

“Migration,” The Economist: Special Report May 26, 2016. http://www.economist.com/news/special-report/21699314-way-people-talk-about-migration-carefully-modulated-terminological-exactitudes

[24] UNHCR, “Compact for Migration,” http://refugeesmigrants.un.org/migration-compact

[25] World Economic Forum, “Global Risks Report 2016,” 11th Edition. January 14, 2016, https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-global-risks-report-2016