In the last decade, an unprecedented number of refugees entered Europe, leading to what media and politics are framing as a security crisis. Statements by Viktor Orbán, Hungary’s minister president, from March 15, 2016: “The refugee crisis will lead to the destruction of Europe” are no longer the exception [1]. In light of Britain’s recent withdrawal from the EU, one must wonder if it is the refugee influx or the failure of the European leaders to establish a concise European-wide solution for the problem that leads to the weakening of the Union.

Solving the immigration problem in Europe will require more than passing new laws. The issue of migration in Europe must be examined across multiple scales and with a human, not purely bureaucratic or legal, lens. This project aims to move beyond the dry statistics migration to show that that the flow of refugees is made of many personal stories and experiences that are transformed and deeply affected by law, regulation, and political climate.

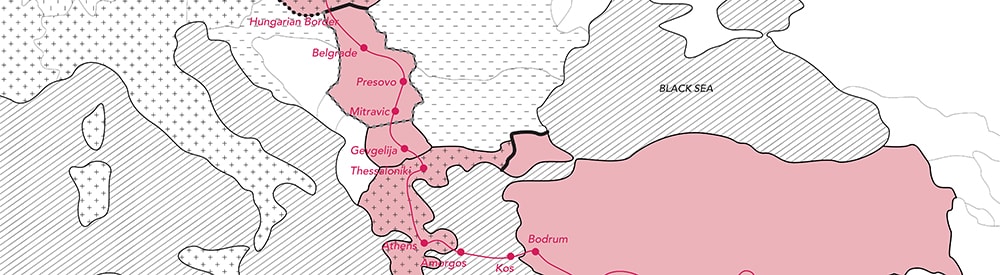

Since 2015, a grisly combination of a surge in refugees from Syria and the increasing number of deaths by drowning in the Mediterranean Sea have made migration over the West Balkan route the primary entry route to Europe for asylum-seekers and migrants [2]. The route begins in Turkey, after which refugees travel through Greece, Macedonia, Serbia, Hungary, Austria and finally continue on to the countries within the European Union in which they intend to seek asylum.

Figure 1: The West Balkan Route.

By analyzing the personal journey that a refugee –Feras, 23, from Aleppo– took to get from Turkey to his final destination in Europe (Germany), and juxtaposing it within the larger European political landscape, we hope to shed light on the different experiences refugees face along the way. Furthermore, through investigating the effects and impacts that the political agendas have on the individual journey–either generating fear of being caught, or feeling welcome and safe at the different stops in different nations–the research highlights the richly textured experience and extreme differences in hospitality an asylum seeker faces as he/she crosses national borders.

In the maps that follow, international regulation and national policy are expressed through modes of transportation–rubber boat, ferry, car, bus, and on foot along train tracks–and through descriptions of interaction with border police, locals, smugglers, mafias, and fellow refugees. Through Feras’s 12-day journey, we seek to reveal the spatialization of policy and regulation on the ground and emphasize the refugees’ reaction to shifts in political climates.

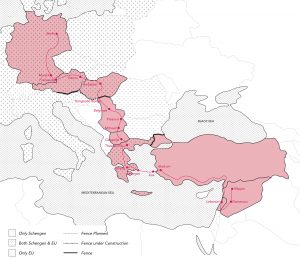

Figure 2: International Refugee Laws. Over the last century, numerous agreements and laws have been established with the goal of creating a common and fair European refugee policy.

Europe has a long history of dealing with mass migration. Over the last century, numerous agreements and laws have been established with the goal of creating a common and fair European refugee policy. The 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol represent key moments and pieces of legislation that defined refugee status, refugee rights, and country of asylum’s responsibilities. But it was not until the Dublin Regulation in 1990 that an asylum seeker’s effective access to asylum procedure was ensured and protected by international law. The Dublin Regulation identifies the member states responsible for the examination of an asylum claim in Europe [3]. These efforts have their limitations, as not all European countries have signed such agreements: Hungary is not a member of the 1951 Convention [4], Macedonia and Serbia among others are not enforcing Dublin Regulation.

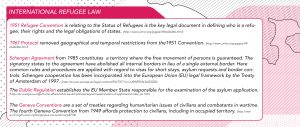

Figure 3: Feras’ journey, days 1-4: The map traces a part of the journey that Feras, a 23-year-old economic student from Syria, takes to migrate to Germany. The 12-day-trek begins with a frightening rubber-boat ride from Bodrum, Turkey to Kos, Greece where Feras and his fellow refugees find rest in tents set up along the coast. This is where the reporter Paul Ronzheimer meets the group of men. From Kos, they continue their journey together by ferry to Athens on Day 4. Source: Bild Reporter’s Paul Ronzheimer’s Periscope video [5].

During the last year, the mood and resulting changes in refugee policies and regulations have transformed from the German ‘open arms politic’ to a more xenophobic tendency. Right wing parties have become increasingly influential throughout Europe. On March 1, 2016, the Europe of Nations of Freedom (ENF) a party with a far-right politics ideology, reached as much as 5.1% in the European Parliament for the first time [6]. The 2015 general election for the Austrian prime minister position resulted in the first round with 36.4% of all votes for Norbert Hofer, the candidate of Austria’s right-populist Freedom Party Austria (FPÖ), who based much of his platform on anti-refugee policies [7]. In August 2015, Macedonia declared a state of emergency and deployed riot police to cut off migration flow at its border; in February 2016, Austria introduced a 37,500 limitation of refugee entries per annum [8]. Hard-right populism recently got its biggest victory with UK prime minister Theresa May’s successful campaign for Brexit in which the ongoing refugee crisis played a crucial role. This year, the French National Front’s candidate Mary Le Pen got her victory for being the first far-right candidate getting into the second round of the election albeit losing to the centrist Emmanuel Macron in the end [9]. These differences in the complex and quickly changing political system make it extremely difficult for an asylum-seeker to navigate along a West Balkan route that grows increasingly hostile to asylum-seekers and refugees.

In addition, the settlement and support of refugees is treated as a national problem instead of a European one. Each country in the European Union has its own policy and attitude towards refugees; creating a patchwork of politics that is difficult for asylum-seekers to navigate and creates a rift between the countries. Heated debates arose over the reception and distribution of refugees. While Germany called for a European-wide solution, Hungary and Macedonia unilaterally decided to construct fences at their borders, many border controls are reinstated within the EU’s visa-free Schengen zone. Due to all these conflicting standpoints, many caution against the disintegration of the European Union as a result of inadequate responses to the current migration issue [10].

Figure 4: Feras’ journey, days 5-9: After Feras and his friends arrive in Athens on Day 5, they travel by bus to the border of Macedonia. Here have their first experience of highly ambiguous national policies. While the Greek police tell them this would be the best way to cross the border, the Macedonian police tries to hold them up. On Day 7, while traveling by taxi to the Serbian border, the group has to hide and run from both the Serbian police and Mafia. In Belgrade, they wait on Days 8 and 9 for a prearranged contact to get their money for the rest of the journey. Source: Bild Reporter’s Paul Ronzheimer’s Periscope video [11].

Europe will continue to face an ongoing flow of migration, as long as there is no definite peaceful future in Syria and other countries in the Middle East and Africa. The European Union is called upon by many member states to decide and implement a common European solution. So far the EU made a deal with Turkey agreeing to stop the irregular migration from Turkey: “all new irregular migrants crossing from Turkey over to Greek islands will be returned to Turkey; and for every Syrian returned to Turkey from Greece, another Syrian will be resettled from Turkey to the EU” [12]. Although it is a step toward a European-wide effort to improve the migration issue, the deal seems like a last minute drastic measure to displace the problem rather than actually solving it. The need for a concise European intervention that embraces migration is acute and urgent.

Figure 5: Feras’ journey, days 10-12: Feras and his friends continue their journey on Day 10 by bus to Hungary. Here, they wait through the night to cross over the first EU country’s border. They are most afraid of being caught by the Hungarian police, due to the Dublin Regulation. Following train tracks, they reach a gas station in Hungary without being caught. Here a Hungarian offers to take them in his car to the German boarder. On Day 12, the group finally arrives in Freilassing, just across the German border, where Feras and his friends apply for asylum. Source: Bild Reporter’s Paul Ronzheimer’s Periscope video [13].

This research seeks to reframe the current conversations around the issue of migration through a detailed investigation of the process by which asylum seekers navigate modern legal barriers and cultural challenges. Our study focuses on how international laws and national customs evolve into spatialized forums where physical manifestations of regulatory institutions impact the arc of refugees looking to settle into a new country.

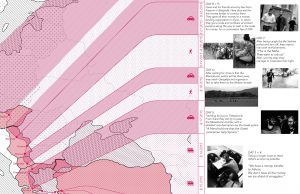

Figure 6: Paul Ronzheimer, the Bild reporter who traveled with Feras and his friends, reporting on their journey using live videos.

The full project mapping can be viewed at full resolution here.

Tami Banh Tami is an architecture student from Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. She had a Bachelor of Architecture from the University of Southern California and is concurrently pursuing Master in Architecture II and Master in Landscape Architecture I Degree at Harvard Graduate School of Design. Tami’s design and research explore the interconnection between architecture, urbanism, ecology, and politic. Her works have been exhibited at Annenberg Space for Photography in Los Angeles (Sink or Swim Exhibition), and Harvard Graduate School of Design (Platform 9: Still Life and Designing Justice Exhibition). Before coming to Harvard GSD, Tami was working at ZGF Los Angeles and was part of the design team for the Samuel Oschin Air and Space Center – the new home for NASA retired Endeavour Space Shuttle. Recently awarded with the Penny White research fund, Tami is currently pursuing a personal research about the history of ecological intensification in the Lower Mekong Delta and the role of maps in constructing new spatial and political realities in the region.

Antonia Rudnay started her training as a landscape architect at the University of Horticulture in Vienna, Austria, followed by a year at the Corvinus University in Budapest, Hungary. It was during this time that her interest in the interconnection of culture and physical space awoke. Indeed it was the different cultural perceptions leading to altered interactions of people in these very spaces that were at the core of her studies. To further explore these questions pertaining to space, Antonia obtained a bachelor degree of Landscape Architecture at the Technical University of Munich, Germany, in 2014. Thereafter she embarked upon a masters degree in Landscape Architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, graduating in May 2016. At Harvard, Antonia refined her approach in a variety of projects dealing with contemporary architectural sites in the US, as well as in Mexico, Colombia and Israel, and their respective social issues. In this vain, Antonia continues to explore the impact of spatial patterns on socio-political conditions, focusing especially on issues of inclusion and exclusion. One of her projects in this field was shown at the Designing Justice Exhibition at the Harvard Graduate School of Design held in spring 2016. Upon graduating, Antonia started working for the Munich-based office of mahl gebhard konzepte. Here she is targeting urban projects, concerning integrated development concepts for small towns in the region of Swabia. At the moment Antonia is involved with the design of a recreational park leading through the town center of Simbach, which will cater to the demands of an urban public space, as well as protect the town from floods, which caused casualties the previous year.

Antonia Rudnay started her training as a landscape architect at the University of Horticulture in Vienna, Austria, followed by a year at the Corvinus University in Budapest, Hungary. It was during this time that her interest in the interconnection of culture and physical space awoke. Indeed it was the different cultural perceptions leading to altered interactions of people in these very spaces that were at the core of her studies. To further explore these questions pertaining to space, Antonia obtained a bachelor degree of Landscape Architecture at the Technical University of Munich, Germany, in 2014. Thereafter she embarked upon a masters degree in Landscape Architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, graduating in May 2016. At Harvard, Antonia refined her approach in a variety of projects dealing with contemporary architectural sites in the US, as well as in Mexico, Colombia and Israel, and their respective social issues. In this vain, Antonia continues to explore the impact of spatial patterns on socio-political conditions, focusing especially on issues of inclusion and exclusion. One of her projects in this field was shown at the Designing Justice Exhibition at the Harvard Graduate School of Design held in spring 2016. Upon graduating, Antonia started working for the Munich-based office of mahl gebhard konzepte. Here she is targeting urban projects, concerning integrated development concepts for small towns in the region of Swabia. At the moment Antonia is involved with the design of a recreational park leading through the town center of Simbach, which will cater to the demands of an urban public space, as well as protect the town from floods, which caused casualties the previous year.