“Populations move…Migration is a process by which organisms track resources, discover, and escape. The patterns of migration reflect spatial and temporal changes in the landscape. Species also shape the environment as they move through it. The design of our cities can facilitate or inhibit migration…Which flows do we want to encourage, and which to block?”

Scenario Journal, 2016 [1]

00: Introduction

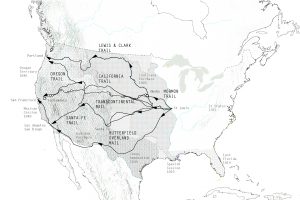

The geographic and cultural history of the United States is largely a chronicle of transcontinental migration and westward expansion. The epic story, both celebrated for its heroic conquests and decried for it devastating social and environmental impacts, comprises a number of well-known chapters including The Louisiana Purchase (1803), Lewis and Clark’s subsequent exploration of the territories (1804-06), The California Gold Rush (1848), The Homestead Act (1862), The Transcontinental Railroad (1863-1869), and more recently the massive tech migration to Silicon Valley (1970s-present) and influx of Mexican nationals to California (1980s-present).

Historian Leo Marx famously contends that the larger narrative of westward expansion was built on three foundational themes, each integral to the American psyche: the first involved the vastness of the physical territory, which was virtually unimaginable to the 19th century European mind; the second encompassed the cultural opposition between the eastern portion of the country, thought to be civilized and constrained, and the west, supposedly raw and untouched; and the third comprised the inclination towards geographic conquest, which was well-steeped in a Protestant ethos that characterized the natural world as lawless and in need of redemption [2].

Emmanuel Leutze, “Westward the Course of Empire” (1861) Source: Smithsonian American Art Museum, Bequest of Sara Carr Upton.

Nowhere has the American disposition towards geographic conquest been more apparent than in the cultivation and maintenance of water resources. Federal dam and water projects in the American West appeared as early as 1877 when the Desert Land Act began gifting land to local farmers who agreed to irrigate their land. The Boulder Canyon Project Act of 1928 exemplified an early effort to introduce flood control, hydroelectric power, irrigation, water access, and recreation. Between the years 1945 and 1975, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Bureau of Reclamation undertook a dramatic dam-building campaign that impacted virtually every watershed across the American West [3]. This collective history reveals a cultural disposition to harness water resources for financial gain and perceived public good, all while enabling continued westward migration [4].

The Continental Compact proposes a new chapter for the American story, one that continues to leverage water resources for public good, but does so in a more ecologically viable way. In this alternative narrative, Americans make a radical retreat from the mythology of westward expansion, opting instead for a massive reinvestment in regions where water resources remain abundant and underutilized. This premise has very real origins in the current events of the State of California—geographic and spiritual mecca for westward expansion, yet home to recurring droughts that make continued migration virtually impossible. Continued westward migration relies on a continuous campaign of mechanical water conveyance, maintained via a massive, expensive, and ecologically devastating system of aqueducts, canals, pipes, and pumps.

This proposal contends that the next wave of transcontinental migrations will head east, supported by shifting public policies that stop moving water to people and start moving people to water. These transformational policies will forsake a historical desire to exert dominion over natural resources, instead adopting a more pragmatic approach that acknowledges the opportunities and constraints of local watersheds.

A Summary of Westward Expansion 1803-1850.

01: The Continental Compact

The water crisis in California is first and foremost a political crisis. Decades of public policy have created a massive system of water conveyance, fostering a fundamental misalignment between the supply and demand of water. An elaborate slew of public policies maintain the untenable status quo in California, which supports a system of water-trading between western states.

The Continental Compact sets the stage for a series of new transnational agreements that adhere to three simple principles:

- Guide population growth towards water.

- Allow water-starved regions to shrink via attrition.

- Return the river to its hydrologic course.

President Truman signs act granting consent to the Upper Colorado River Basin Compact (1949) [left]; California Governor signs the proposed Continental Compact (2020) [right].

02: The Ground Water Crisis

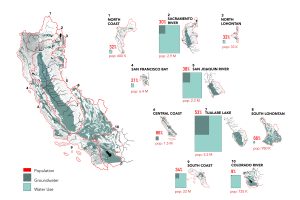

This taxonomy of water basins illustrates the existing lack of equilibrium in California, where existing ground water supply fulfills a relatively low percentage of local demand. California maintains this unbalanced system through massive water conveyance via aqueducts and other hydraulic methods. This system externalizes significant environmental costs, most of which are borne by state and federal governments.

This taxonomy of California Sub-Basins illustrates the lack of equilibrium between population, ground water, and water use.

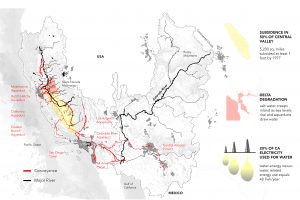

Three of the most damaging environmental impacts include subsidence, the sinking of land due to unbalanced groundwater extraction; delta degradation, which threatens potable water supply, sediment, and the balance between fresh and saline water; and energy use, which results from the operation of the energy-intensive aqueduct system. Policy-makers have diverted the Colorado River, for example, to feed southern California’s Imperial Valley and the cities of San Diego and Los Angeles. This decision continues to decimate local ecologies and communities in the Colorado River Delta and the Gulf of California in Mexico.

California draws a significant portion of its water from the Colorado River Basin using an elaborate conveyance system of aqueducts, canals, pipes and pumps, shown in red above. This system leads to negative consequences including subsidence, delta degradation, and increased energy use.

03: Moving from Hydraulic Urbanism to Hydrologic Urbanism

The Continental Compact proposes to fundamentally alter the culture of water-trading by re-legislating water distribution throughout the United States, Mexico, and Canada. In this alternative narrative, regions reject large-scale hydraulic urbanism—which supports growth in water-starved regions by delivering water via energy-intensive aqueducts—and embraces the emerging possibilities of hydrologic urbanism—which invests in lower-intensity growth patterns while leveraging existing water resources.

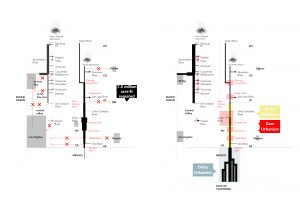

Hydraulic Urbanism utilizes energy-intensive water conveyance to move water to people [left]; Hydrologic Urbanism leverages existing watersheds to build communities where water already exists [right].

04: Hydrologic urbanisms

The Continental Compact provides a long-term solution to the contradiction that is California, incentivizing urbanism in water-rich basins near dams, along rivers, and within deltas. Each of these landscapes inspires a unique urban typology, designed to leverage resources that are unique to the local watershed. Dam Urbanism is centripetal in form, embracing and utilizing the existing multi-purpose dams and reservoirs while providing localized hydropower and water supply for large and concentrated populations. River Urbanism is linear in form, beginning at tributary confluences, paralleling and working with the flows of rivers while providing diverse mixes of urban, suburban, and rural densities for dispersed populations. Delta Urbanism is branched in form, growing with the natural distributive flows of a fanning deltaic context over time, providing gradients of high and dry occupations and distributaries of low, wet occupations in brackish marshes.

The three hydrologic urbanisms leverage existing water resources to create multiple conurbations at the scale of the river basin. These conurbations transgress local, state, and national boundaries. Locally, each responds to the specific characteristics of its riverine, geographic, and landscape environment. The hydrologic urbanisms are capable of accommodating diverse programs including agriculture, residential, ecology, industry, recreation, and tourism.

The three hydrologic urbanisms leverage investment in existing dams, rivers, and deltas to create urban conurbations at the scale of the river basin.

05: Redefining the Hydrologic Region

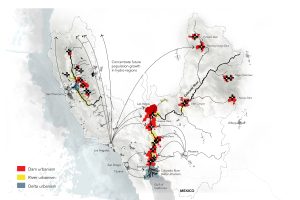

The Continental Compact promotes infrastructural investment in existing water-rich basins, thereby incentivizing growth in a series of hydrologic regions. The resulting megalopolis allows new water-rich landscapes to grow throughout the twenty-first century and beyond. Conversely, it allows existing water-poor landscapes in Los Angeles, San Diego, San Francisco, Phoenix, and Denver to shrink slowly via attrition. The positive environmental and financial benefits of the revised policy will be significant: saving energy, reducing carbon emissions, slowing subsidence, lowering infrastructure costs, and regenerating river deltas in the United States, Mexico, and Canada.

Infrastructural investment in dams, rivers, and deltas incentives population growth in water-rich landscapes. Meanwhile, water-poor landscapes shrink through attrition.

06: Moving from Westward Expansion to Eastward Migration

The history of 19th Century westward expansion in the United States leveraged abundant natural resources to grow the country. Things are very different today: land is expensive, resources are scarce, and state and federal governments are increasingly unable to afford the spiraling price tag associated with infrastructural obligations. In this context, we suggest that the next large-scale migration in the United States might be eastward, towards regions in the Midwest, Northeast, Gulf Coast, and Upper Great Lakes where water resources are plentiful.

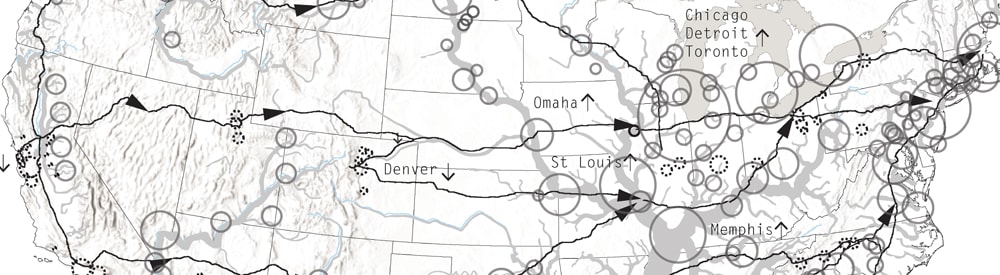

Proposed Eastward Migration: 2020-2050.

07: From Megaregions to Hydrologic regions

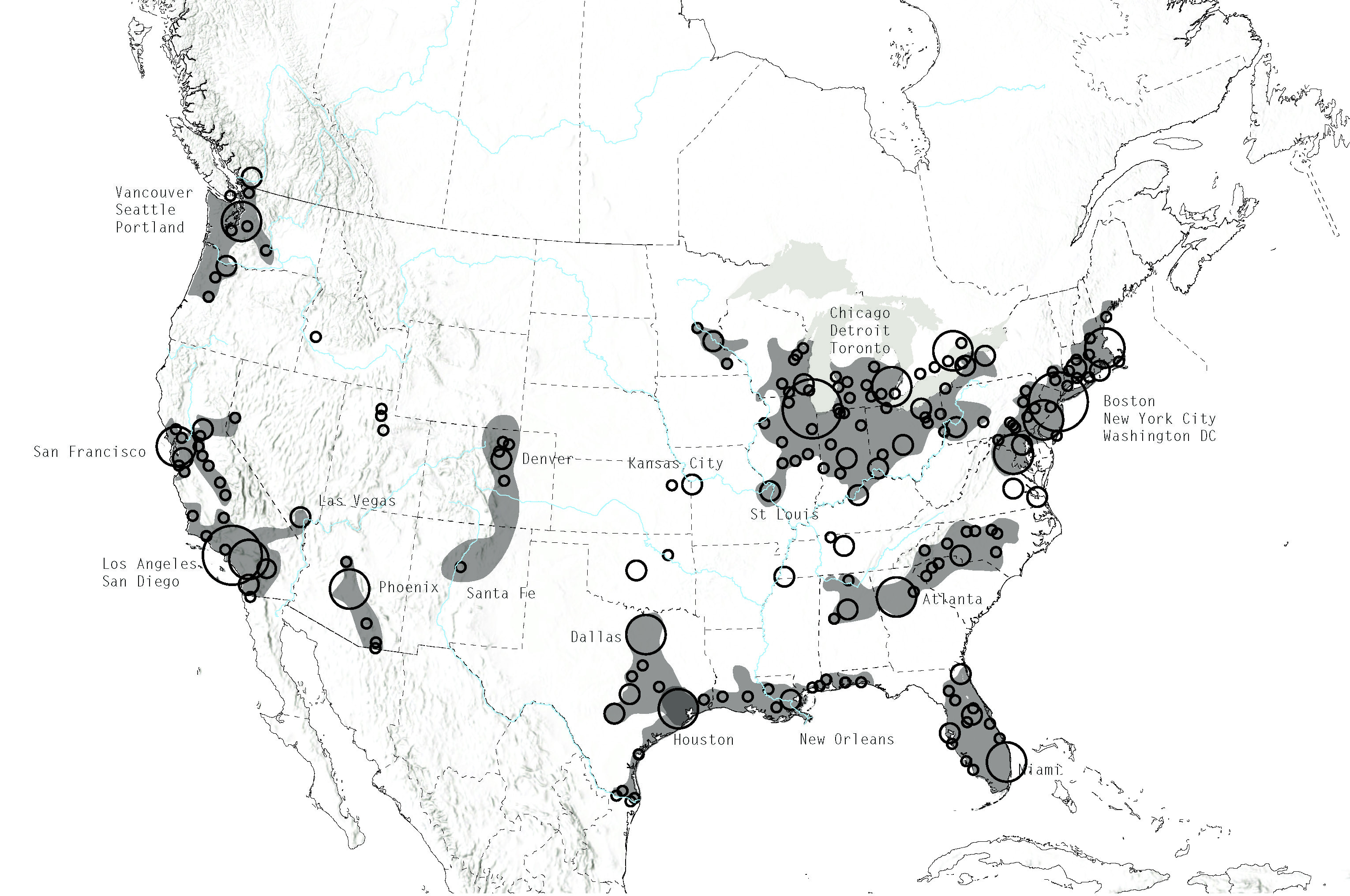

The Regional Planning Association forecasts that urban growth in the United States will produce eleven megaregions by 2050. The Association suggests that six major trends will shape the country’s growth: global trade patterns, demographic expansion, inefficient land use, inequitable growth patterns, global climate change, and aging metropolitan infrastructure. They further recommend that federal policy-makers utilize a megaregional model to guide decisions regarding large-scale infrastructural investments [5]. Remarkably, these growth projections don’t factor what will possibly become the most critical determinant of successful urbanism: water supply.

The Continental Compact recommends that policy-makers begin shifting their focus from megaregions to hydrologic regions, investing in water-rich local urban conurbations built around dams, rivers, and deltas. The Continental Compact re-invests the massive resources that support the existing aqueduct system into the construction and maintenance of new infrastructure in water-rich regions. This strategy reprioritizes ecological sustainability at the continental scale, renouncing our historically antagonistic relationship with local watersheds and topography, transcending national boundaries as required. The result will be a series of eastward migrations, supported by public policies that stop moving water to people and start moving people to water.

Megaregions 2050 [5].

Proposed Hydrologic regions 2050.

Ian Caine is a registered architect and urban designer who explores the form, processes, and impacts of suburban expansion. He is an assistant professor at the University of Texas at San Antonio and Researcher with the Spatial History Project at Stanford University, where he is leading a multi-disciplinary effort to create an interactive timeline of suburban growth for San Antonio. Caine’s collaborations with Derek Hoeferlin have received recognition in the Rising Tides, Build-a-Better-Burb, and Dry Futures competitions. His work has appeared in Log, MONU, Sustainability, Metropolis P/O/V and popular press outlets such as The Discovery Channel, NYTimes.com, the San Francisco Chronicle, and Texas Public Radio. Caine holds a SMArchS degree in Architecture and Urbanism from M.I.T., B.A. in Political Science, and M.Arch from Washington University, where he received the A.I.A. School Medal.

Derek Hoeferlin, AIA, is principal of [dhd] derek hoeferlin design and associate professor at Washington University in St. Louis. He collaboratively researches integrated water-based design strategies through his leadership role in Way Beyond Bigness: A Watershed Architecture Manifesto and Methodology (www.watershed-architecture.com). Derek was a core member for STUDIO MISI-ZIIBI, a winning team in the Changing Course: Navigating the Future of the Lower Mississippi River Delta competition. Derek helped lead the Unified New Orleans Plan for post-Katrina recovery and rebuilding efforts. He has held lead design roles with Waggonner & Ball on multiple award-winning projects, including Dutch Dialogues and the Greater New Orleans Urban Water Plan. Derek collaborates with Ian Caine, including competition honors for Rising Tides, Build-a-Better-Burb and Dry Futures. His work has appeared in Metropolis Magazine, ‘scape Magazine, New Orleans Under Reconstruction: The Crisis of Planning, among others. He holds B.Arch and M.Arch degrees from Tulane, where he received the A.I.A. School Medal, and a post-professional M.Arch II degree from Yale.

Derek Hoeferlin, AIA, is principal of [dhd] derek hoeferlin design and associate professor at Washington University in St. Louis. He collaboratively researches integrated water-based design strategies through his leadership role in Way Beyond Bigness: A Watershed Architecture Manifesto and Methodology (www.watershed-architecture.com). Derek was a core member for STUDIO MISI-ZIIBI, a winning team in the Changing Course: Navigating the Future of the Lower Mississippi River Delta competition. Derek helped lead the Unified New Orleans Plan for post-Katrina recovery and rebuilding efforts. He has held lead design roles with Waggonner & Ball on multiple award-winning projects, including Dutch Dialogues and the Greater New Orleans Urban Water Plan. Derek collaborates with Ian Caine, including competition honors for Rising Tides, Build-a-Better-Burb and Dry Futures. His work has appeared in Metropolis Magazine, ‘scape Magazine, New Orleans Under Reconstruction: The Crisis of Planning, among others. He holds B.Arch and M.Arch degrees from Tulane, where he received the A.I.A. School Medal, and a post-professional M.Arch II degree from Yale.

Emily Chen, M.Arch/MLA, Washington University in St. Louis.

Tiffin Thompson, M.Arch, Washington University in St. Louis.

Pablo Chavez, M.Arch, University of Texas at San Antonio.