We don’t own our passports. They belong to the country that claims us. We use passports to move between borders we have created. These documents are as relevant as the internet and tell stories as timeless as a Greek tragedy. Our sense of belonging is deeply tied to passports and the immigration process, which is increasingly complicated and scrutinized.

Caressing the bound, wallet-size travel document Marco waits while I pull up a collection of forms, documents, and website tabs. All are to prepare us for our journey tonight. I am assisting Marco, a permanent resident of the United States who arrived as a refugee, in applying for United States citizenship. This is a final step in a long and complex journey for Marco, a process that speaks to the very collision of humanity and bureaucracy. Marco is seeking a profound signifier of belonging, a United States passport.

If we’re lucky, we’ll complete this tonight. If not, Marco will gladly take home his stack of paperwork along with my carefully prepared instructions on how to locate a necessary document at the DMV or the specific type of passport-style photo he needs. He will assure me that he will get this done. He will nod and take his papers, but he will probably disappear into this rust belt city, the stack of papers put aside in the shoddily partitioned apartment carved out of a gilded-age mansion, bed sheets covering the windows in the room where he lives.

Form N-400, Application for Naturalization. Photo by Alexandra Lillehei.

Once a month I walk over to a tired, run-down building next to the bus depot downtown to assist permanent residents with their citizenship applications through a volunteer program. After showing my ID, I have access to a windowless cubicle and a ten-year-old computer where I sit with my clients preparing stacks of forms. Here, my clients tentatively hand over green cards that bear one small difference to those held by the researchers and business executives with whom I normally work – a small two-digit code printed on the card. If you speak the language of immigration, the code distinguishes these clients as asylees or refugees.

Marco’s card number tells me he is a refugee from Burma. That number is the reason that Marco is here tonight, with a crumpled social security card and a stack of documents that mean everything to him and his place in this country. Often used interchangeably, asylee and refugee can be two very important distinctions in the immigration world. Because Marco is classified as a ‘refugee,’ it means that he applied for entrance to the United States from abroad and fit within one of the refugee populations defined by the United States government. An ‘asylee’ must apply for protection when they are already in the United States and must show that they would be in danger if they left the United States because of their membership in a particular group or due to their race, religion or other defined category. While this may seem like splitting hairs, the immigration process takes terms like these very seriously. For example, the term “immigrant” is often widely used. In the immigration context, however, an “immigrant” is someone who comes to the U.S. on a long-term, permanent basis. A “non-immigrant” on the other hand, is someone who seeks temporary entrance, like on a work or student visa.

The complexity in these terms speaks to the larger intricacies in our immigration system, particularly in this charged political climate. Many individuals in the United States here without authorization are cases of overstay. They arrived with authorization and a purpose, but when the time came to leave (for example, when their studies ended or when their visitor status expired), they did not book a flight and return home as promised. And although it seems like this would trigger ICE agents with guns lurking around every corner for these overstays, many of these individuals create lives and years go by. They marry United States citizens, have children and find employers who will hire them. They pay taxes and are our neighbors. Perhaps ICE “raids” are increasing now, but many of these individuals live their lives, albeit fearful that one day their number will be up. Deportation is not typically a quick, one-way trip out of the country, however. Like any good government process, deportation is nuanced and bureaucratic with a progression of court dates and perhaps a scheduled “leave” date, that is sometimes officially declared “voluntary departure.”

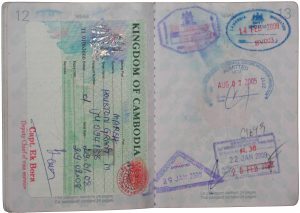

Marco hands over his travel document, a simple document that can often open Pandora’s box. The document itself, like most passports and travel documents, contains significant security features. Many of these documents reportedly contain more than 60, including chips, holograms and foil seals. A criticism of this “enhanced technology” is that even border officers can’t possibly remember all of the features that are supposed to distinguish “fake” and “real” documents.

Because Marco’s country of origin is Burma, I examine his travel document carefully. This travel document is not a Burmese passport but is instead issued by the United States. Sometimes when refugees are granted permission to come to the United States, they are required to hand over their passports and promise never to return to their home country again. This is because many times they are claiming to be in fear for their lives in their home country – how could they be able to return if this were the case? This also means, however, that any family or loved ones they leave behind they may never see again. Since Marco gave up his Burmese passport, the travel document allows him to travel to “approved” countries and return to the United States.

“Have you been back to Burma?” I ask tentatively, flipping through the travel document as if I have a right to know where he’s been, what he’s seen.

“Myanmar?” He corrects me, lifting his chin slightly. “No.” I pick up on his use of “Myanmar” as opposed to Burma. The United States still officially refers to the country as “Burma” even though the nation’s leadership renamed the country “Myanmar” two decades ago. The United States’ refusal to use the new name is an oppositional stand against the leadership and its doings.

I see Thai entry stamps in his passport. I’ve heard that to see their families, Burmese refugees often fly to Thailand and travel through the porous border into Burma/Myanmar. It is very similar, in fact, to the way that ISIS/ISIL followers cross into Syria from Turkey and other neighboring countries. These borders lack uniformed officials waiting to accost passports with proof of entry here, a scarlet mark there.

Cambodia, Thailand, and US visa. Photo by Houston Marsh.

But Marco has told me no, so we must take his word for it. His story is personal, but it is not new, and he is not asking for your sympathy. Marco is in my office asking for empowerment on an otherwise unremarkable Thursday night. Marco and the other clients whose paperwork passes over my desk are here, slogging through this system with patience. They have waited for the privilege of applying for citizenship with perseverance I cannot imagine. Before arriving here at my desk, Marco and the many others who share his story have waited years. They have waited first to be proven worthy of the stamp Refugee, then to be issued permanent residence and then another five years before applying for citizenship and a final belonging.

I take the papers he hands me, fading photocopies that have been sloshed around at the bottom of bags and worked on at the kitchen table, tea and food marking worn the corners.

“Okay, we can start with the addresses.” I read him the first question, “Where have you lived the past five years? We have to begin with the most recent address and work backward.” I look at what he has written down on the paper, one address.

“Is this where you live now?” I ask, pointing at an address in the inner city where at least a couple of deadly shootings have taken place this year. He nods his assent.

“When did you start living there? The month and the year?” He scrunches his face up in concentration. We really should be as specific as ‘month/day/year’ if we are following the instructions completely. However, this man estimates, counting back the calendar months using his phone. He mutters “sister’s wedding” and “big storm” under his breath. We eventually agree upon mid-July of this past year as the move-in date.

“Now before that, you were living…?” Four more years to go. Google is our genie, our saving grace in this work. I don’t know how this ever got done before. Help with the zip codes for one is a small miracle. When we get to “Employment History,” Google is a downright prophet. For example, a few weeks ago I sat with a Cuban man as he talked me through his extensive employment history.

“I was driving a truck for this one company… it was products for Aldi’s, but the company was based in Kentucky. It had ‘Green’ in the name,” He told me. A few minutes of typing and clicking I was able to gleefully enter ‘Green Moving Associates LLC’ on the form along with a complete address. With the Cuban man, the travel record alone also took us about an hour to complete. Unlike Marco, this man was an asylee and allowed to return home to Cuba for visits (talk about a contradiction in government rules). But it is very important that the visits did not add up to more than six months in any given year, or his ties to the United States would be questioned in the citizenship application.

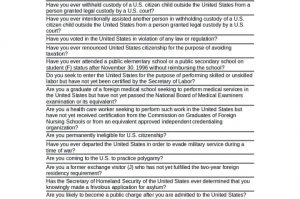

Tonight, Marco and I are nearing the end of his application. He has already fielded two calls from his wife at home (asking the Burmese equivalent of how long can this possibly take?). We are now at the section I like to call “Die for your Country.” I read a series of questions that confuse Marco deeply.

“I didn’t know there was forced military!” He exclaims, and I have to explain what a draft is and how there hasn’t been one for a very long time, but, on the off chance there is, he needs to be willing to serve.

Green Card Questionnaire. Photo by Cory Doctorow.

We must mail in the application. It seems funny to me that while so much of my work entails searching for convoluted records in government databases, it also rests on my ability to carefully compile photocopied forms, affix them with paperclips and check mailer envelopes to make sure I have the correct address. The boundaries we construct around ourselves are simple in theory. The categories that we use to define nationality and citizenship appear strictly legal and transactional: refugee, asylee, foreigner, citizen. But when we construct the rules and processes of these categories, the boundaries flex and bend to politics. What rules govern who is allowed to come here? Under what circumstances? Like the Burma/Myanmar distinction and the inability to travel home for some but not others, the boundaries may seem arbitrary at best.

Like the passport security features, the rules and loopholes have become so complicated they can seem indistinguishable and meaningless. Marco is one of the lucky ones. His application is completed, signed and sealed, waiting in the mail bin. After several more months of waiting, fingerprinting, security checks, language, and civics tests, he may be presented with his own United States passport that confers with it the privilege of belonging.

Feature image by Camilo Rueda López.

Header Image by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS).

Audrey Burns Leites is a global mobility professional and writer living in Rochester, New York. She is a graduate of Syracuse University’s Writing Program, has studied at the University of Rochester and conducted research in Germany and the Czech Republic. Leites’ writing experience spans a variety of genres. Her research interests include the intersection of globalism and humanism. Leites co-founded the lifestyle blog Hearth & Sprout. She co-edited the publication Pro(se)letariets: The Writing of the Trans-Atlantic Worker Writer Federation (2011). Her recent work has appeared in the Journal of Languages and Culture, Journal of Educational Planning, Policy and Administration, PopMatters, and Literary Traveler, among others.