Detroit is expansive. The culturally significant eight mile road is just that, a survey baseline 8 miles from the river’s edge, marking the boundary line between city and adjacent suburbs and towns. The city itself is 143 square miles in area (approximately 370 square kilometers), large enough to fit all of Manhattan, Boston and San Francisco within its boundaries. Area is a challenge in Detroit, but even more so, vacant area is a challenge. Of the 143 square miles, twenty percent or 28 square miles registers as vacant, and thirty percent or 41.5 square miles is contained within the right-of-way. Detroit is a city whose fabric is dominated by detached houses and free-standing buildings, making demolition possible and prevalent. While the vacancy is concentrated in some areas, the overall pattern is unplanned, perforated and varied.

Proposed Landscape Structure. Image © Stoss Landscape Urbanism

The voids range in scales, formats, morphologies, locations, past uses, toxicity, perception, land cover, all resulting in differing suitability for new uses. When left relatively untouched, ecological succession occurs on vacant lands, providing measurable and valued ecosystem services. Yet, these abandoned swaths, admirable for their reproductive and sustainable tendencies, [1] underperform culturally and socio-economically. It makes sense to conserve some land for unhindered ecological transformation and research, but given the varied conditions and the active populations, this cannot be the only solution. Detroit will not be left to gradual re-forestation. Instead, a multi-pronged, multi-scalar approach must be developed, proactively both in the short- and long-term.

A Landscape Infrastructure for Detroit

The necessity of multiple interventions becomes more apparent when considering that vacant land is only one of the many challenges facing Detroit. The eight mile road is a political boundary, but also a socio-economic divide. The racial, economic and health contrasts are stark. Detroit has a predominantly African-American population that faces high rates of poverty and health issues including asthma and heart disease. There is a legacy of industrial pollution and environmental hazards, adversely affecting poor communities. Industrial and residential areas are too close together. The outdated infrastructure cannot support the city’s stormwater, with discharges of combined sewage/stormwater in violation of state and federal standards. The transportation system is inefficient. The education system is inadequate. Entire neighborhoods lack basic services, including access to groceries and fresh produce. The city government does not have the funds and abilities to address these issues. The situation is complex, the extent of environmental and social justice issues pervasive.

Given the current climate, two trends emerge: landscapes are abundant and unavoidable; and past civic landscape typologies—the square and the park—are obsolete in this context. They are too passive, singular and inert to catalyze transformation. Detroit does have squares and parks but they are underfunded, lack maintenance, and are located at the periphery, far from the areas of greatest inhabitation. This presents the opportunity to re-think the civic landscape as a greater system with the potential to be reproductive, generative and structural. When framed properly, Detroit has three assets: land, time and people. The city has been home to innovation throughout its history, and the next chapter is poised to address the urban landscape.

Robust spontaneous meadow, Northeastern Detroit. Photo by Jill Desimini

Stoss Landscape Urbanism, through the writings of its founder Chris Reed and the concepts driving a number of projects, has long advocated for landscape projects that transcend form, object and pure aesthetics to embrace performance, metrics, frameworks and systems. The firm, in moniker as well as practice, espouses landscape urbanism, “an alternative to the perceived limitations of urban design discourse and its nostalgic commitments to density and architectural ensemble as the basic medium of city making. In the context of decreasing physical density, decentralization and sprawl, landscape has been found by many as a medium affording a unique traction on the problematics of the contemporary city” [2]. It is not inconsequential that the thinking around landscape urbanism emerges out of conditions of and design responses to the American Midwest, out of Chicago and Detroit. It becomes logical to then test the practices of a landscape-driven urbanism in its prototypical environment — the unbounded prairie, the decentralized conurbation.

In Detroit, despite the loss of urban density, there remain strong local traditions, occupations and grass-roots initiatives embedded in the contemporary Detroit landscape; art and agricultural practices are robust. The goal is to support these enterprises and extend their impact. Building upon and diversifying these local practices, Stoss puts forward a landscape-driven, strategic framework to guide future types of land use and development for the city. They make a convincing eight-point case for landscape to meet the environmental imperatives facing the city: increasing the value of vacant land, improving citizen health, and providing efficient, cost-effective, green infrastructure.

Landscapes are inevitable; if you do nothing else, landscape will re-establish itself even in the most built-up areas. The many emerging and successional landscapes across the city are testament to this.

Landscapes are cheap — especially relative to other forms of infrastructural or urban development. Landscapes are programmed with the ability to adapt and change to different conditions, so they can require different types and lower intensities of maintenance regimes to sustain them. They can also be tended in different ways, so that community gardeners and urban foresters alike are rendered as stewards and caretakers of public space.

Landscapes are productive and multi-functional. They clean air and water and soil, they make urban environments healthier, they generate resources for food, energy, commerce, and habitat. In this way, they cultivate new kinds of urban landscapes, new kinds of urban experiences, and support a wide range of social interactions and relationships. They help build communities, they can be sites for job training and employment, and can even be economically productive.

Landscapes are effective grounds for research and experimentation. They are sites in which new ideas can be safely and effectively tested for later application across the city and in other cities like Detroit (think of new ways to clean large-scale swaths of contaminated urban soil, for instance).

Landscapes are green. Built properly, they reduce the amount of resources necessary to sustain the city (think of soft rainwater infiltration gardens as opposed to hard pipes and treatment plants). But they also create a lush, rich image and identity for the city — one which competing cities would love to have. Densely developed cities like New York and Boston simply do not have the space to allow landscapes to flourish at the scale and with the impact that Detroit does.

Landscape systems work most effectively across large scales — even regions. So they have an ability to connect and coordinate seemingly unrelated entities (think of how rainfall in Dearborn Heights might make its way to the Rouge River and Rouge Park in western Detroit, and eventually continue through Southwest Detroit to the Detroit River and the Great Lakes). As such, then, they have the potential to structure cities and regions.

Landscapes are enriching; they improve the health of the environment and of the people using them, and they have positive cognitive and visual impacts.

Landscapes buy time. They change and evolve of their own accord, but they can also allow for temporary uses while other larger decisions about a site’s or neighborhood’s future are being decided [3].

The Stoss work is part of a larger planning effort for the Detroit Economic Growth Corporation and a steering committee appointed by Detroit Mayor Dave Bing and consisting of community leaders, entrepreneurs, city staff, and representatives from philanthropic foundations. The effort is funded by the Kresge Foundation, the Ford Foundation, and the Kellogg Foundation. It is directed by Toni L. Griffin and Hamilton Anderson Associates and includes significant contributions from Stoss, Happold Consulting, Teresa Lynch / MassEconomics and ICIC, Interface Studio, Alan Mallach and the Center for Community Progress, the Detroit Collaborative Design Center, and Michigan Community Resources, and Canning Communications. The project began in 2010 and the plan will be published in late 2012 and early 2013.

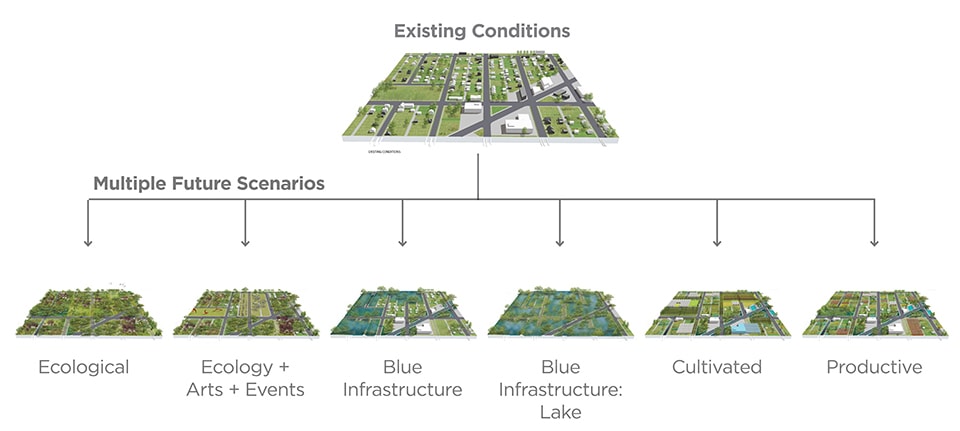

Figure 1 Illustrative Scenarios. Image © Stoss Landscape Urbanism

The intelligence in the Stoss piece is that it recognizes that no one solution will be able to address the complexity of issues facing Detroit; that the strategies must work across scales and time frames; that they must be productive; and that landscapes can best address concerns of environment, health and land value.

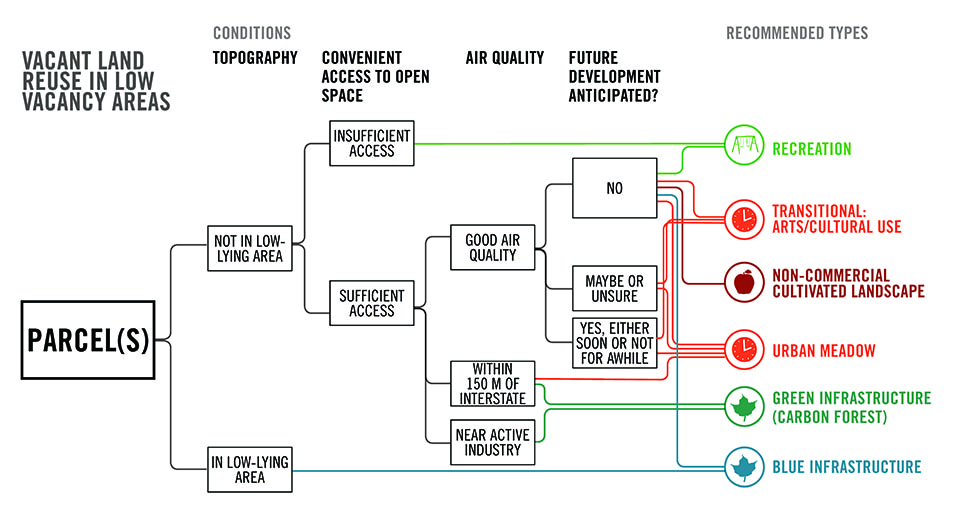

Figure 2 Decision-Making Matrix. Image © Stoss Landscape Urbanism

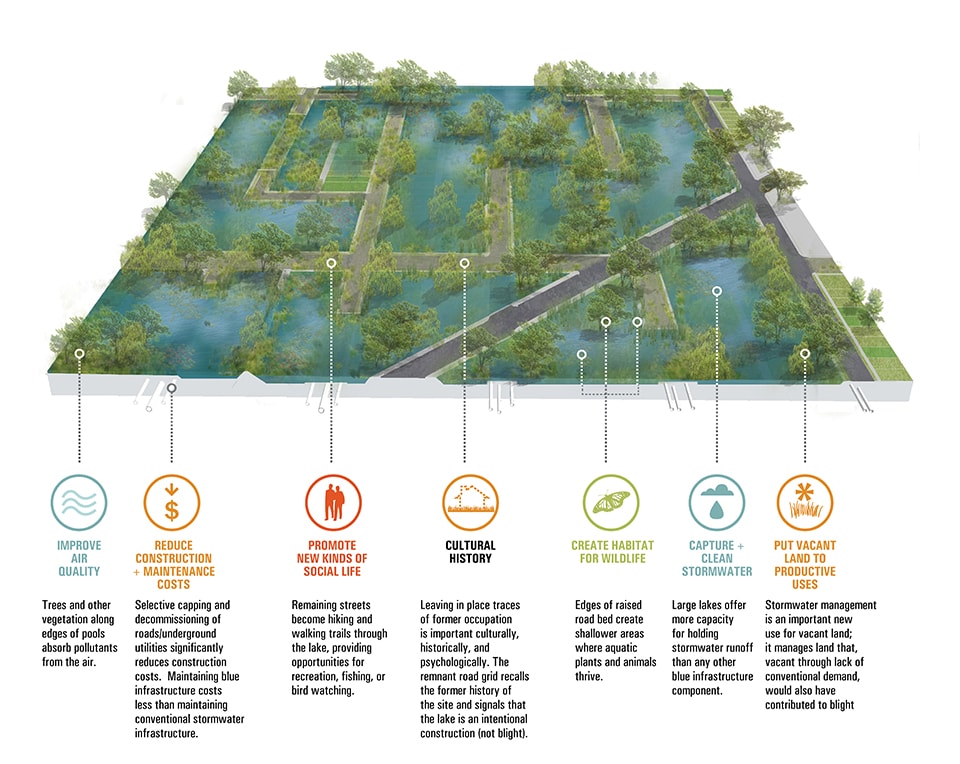

The loss of value in the land rests not only in economic terms, but also in terms of perception and performance. To get an indication of intricacy, the project tests its strategies against thirteen goals: to promote healthy lifestyles, to increase access to healthy foods, to capture and clean stormwater, to clean soil, to improve air quality, to create habitat for wildlife, to stabilize neighborhoods, to research and test new ideas, to reduce maintenance costs, to put vacant land to productive uses, to generate energy, to create jobs and job training opportunities, and to promote new kinds of social life. Behind these goals are a number of bigger ideas about the creation of new urban form for Detroit, ideas driven by the mediums ability to address horizontal expanse, to make connections, to provide services and to evolve biophysically and socio-economically. Ecology is at the forefront, infrastructure is embedded, environmental justice addressed and cultural perception altered. Detroit becomes a model for a green and blue city, something to emulate rather than shun in a pervasively urbanized globe.

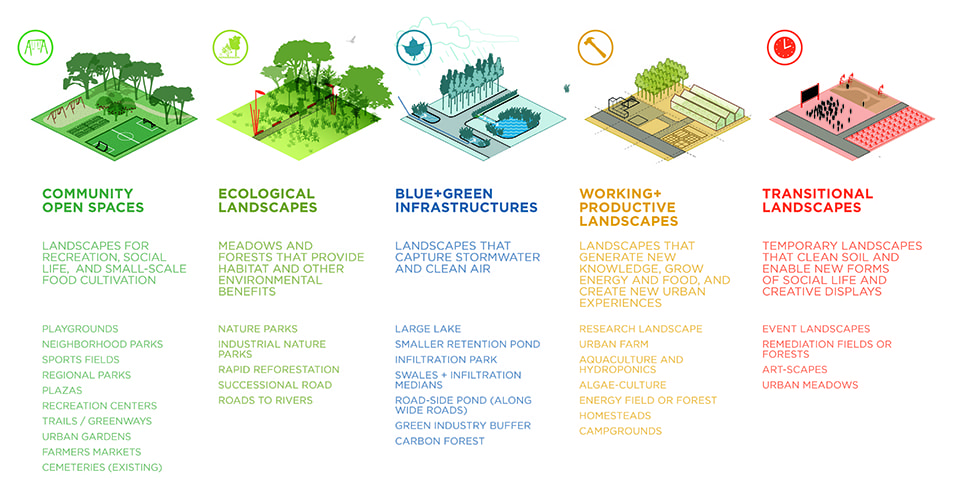

Figure 3 Development Categories. Image © Stoss Landscape Urbanism

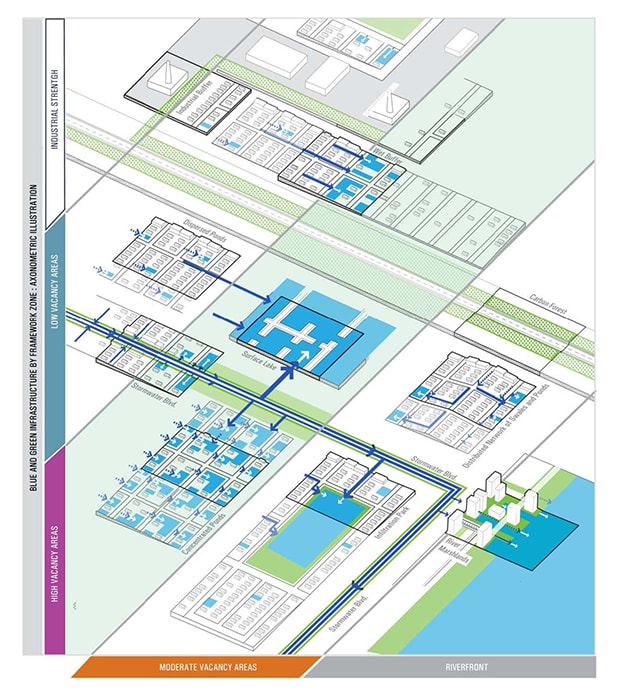

The strategies proposed operate at two levels: development and land use. The development typologies are physical, functional and nest within land use categories. [Figure 3] The land uses belong to the open space category and fit within a larger spectrum of land uses that include new interpretations of city center, residential and industrial land classifications. The land use typologies push the boundaries of traditional zoning categories to include specific visions and performance metrics. These include: blue/green corridors, innovation productive, innovation ecological, and large parks.

The name ‘development typologies’ belies the systematic nature of the proposed interventions but points to their adaptability across scale and their ability to respond to different existing conditions. There are five broad categories: community open spaces which encompass traditional recreational and civic open spaces, ecological landscapes that create floral and faunal habitat, blue and green infrastructures which address stormwater needs citywide, working and productive landscapes that expand existing agricultural and energy operations, and transitional landscapes that celebrate the art and event installations for which the city is known.

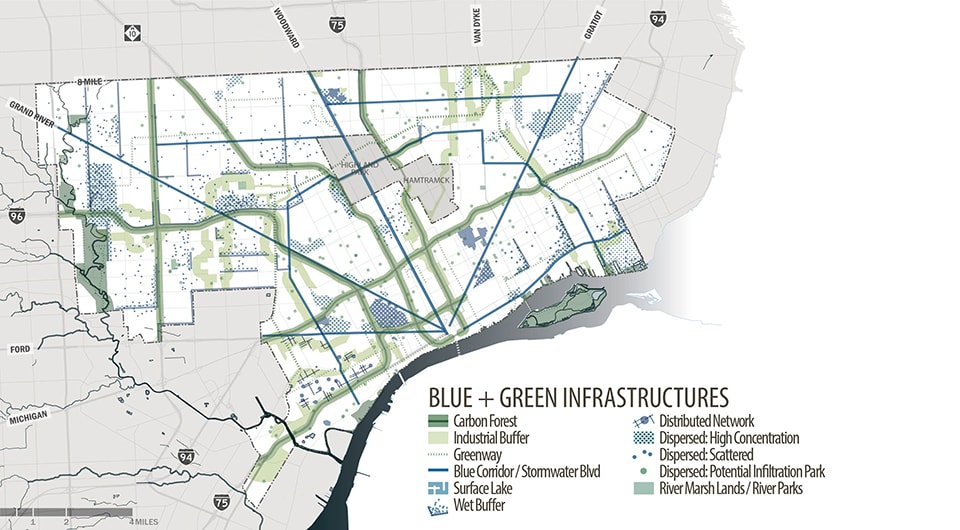

Figure 4 Hybrid Network. Image © Stoss Landscape Urbanism

Water, or more specifically the de-engineering of the previous faulty stormwater management system, drives the proposal. The recognition of the potential of the hydrologic infrastructure to form a landscape backbone for urban development can be characterized as a form of Aquatic agency [4] — often a driver behind Stoss projects. Water and urbanization are interdependent and often the quality of the water resources provides an indicator of urban health. Detroit is a flat city, with a powerful radial street grid, and a severe stormwater problem. In a simple, yet powerful idea, these two combine, and the iconic avenues of the past — Woodward, Gratiot, Jefferson, Michigan and Grand River — transform into blue corridor/stormwater boulevards, retrofitted to convey and store excess runoff.

Figure 5 Blue and Green Framework. Image © Stoss Landscape Urbanism

They become part of a productive network that works sectionally to bring water to surface lakes, dispersed ponds and river marsh lands and parks. [Figures 4-6] Detroit has a long history of development perpendicular to the river, beginning with the French ribbon farms. The hydrological connection is restored with the five stormwater spines. Carbon forests and on- and off-street greenways enhance the linearity while providing buffers from automobile traffic and industry. In addition to these corridors, large patches are aggregated for productive and ecological reserves.

Figure 6 Large Lake Typology. Image © Stoss Landscape Urbanism

The park system is adapted, with underutilized parks transitioning to fill blue infrastructure needs, and new parks and recreational centers constructed in under-served areas. Taken together, a rich landscape network presents a long-term urban structure that is tied into the regional network, and twists Hilberseimer’s notion of urbs in horto.

Figure 7 Initial Inputs and Outputs Diagram. Image © Stoss Landscape Urbanism

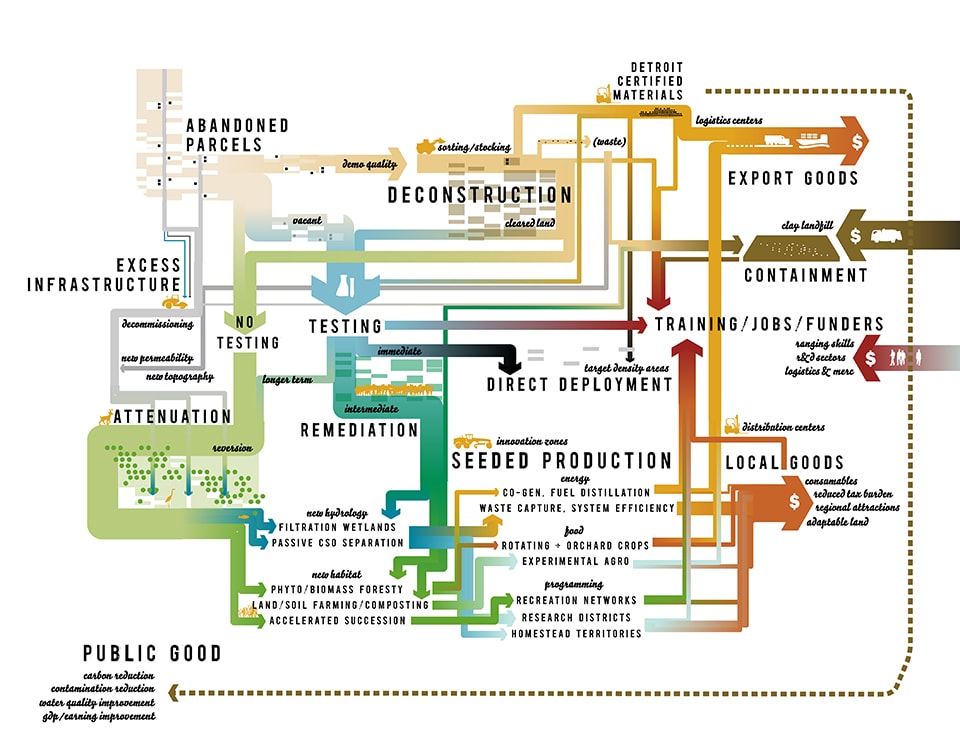

The Stoss scenarios come with a necessary implementation toolkit. The proposed vision is long-term and requires zoning, regulatory and policy changes, as well as land acquisition, partnerships and pilot projects. The design of the project includes the visualization of the decision-making process through intricate flow charts. The project began by understanding the potential productive futures of Detroit with an iconic diagram articulating the necessary inputs and outputs to serve the public good. [Figure 7] Land, time, people, materials and financial resources are embedded in the matrix. Throughout the planning process, this diagram has been mined, expanded, and improved upon to generate a series of provocative vignettes, productive frameworks and optimistic, visionary and sensitive futures for Detroit. The definition of an urban landscape is broadened, while an exemplary landscape planning process is revealed. Cities everywhere, shrinking or not, take notes.

A version of this article was published in The Journal of Chinese Landscape Architecture, 2013, volume 29, 206, 2.

Jill Desimini is an Assistant Professor of Landscape Architecture at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design. Prior to joining the full-time faculty, she was a Senior Associate at Stoss Landscape Urbanism in Boston. She holds master of landscape architecture and master of architecture degrees from the University of Pennsylvania and a bachelor of arts in urban studies from Brown University. Her research focuses on reproductive strategies for abandoned urban lands.

Jill Desimini is an Assistant Professor of Landscape Architecture at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design. Prior to joining the full-time faculty, she was a Senior Associate at Stoss Landscape Urbanism in Boston. She holds master of landscape architecture and master of architecture degrees from the University of Pennsylvania and a bachelor of arts in urban studies from Brown University. Her research focuses on reproductive strategies for abandoned urban lands.